Abba Seraphim’s Christmas Message

During the Divine Liturgy for the Eve of the Nativity Feast, which Abba Seraphim celebrated at St. Alban & St. Athanasius British Orthodox Church in Chatham, he addressed the issue of the secularisation of Christmas. However, he believed it is important for Christians to emphasise the fact that they are not simply celebrating the Lord’s birthday – although “words cannot express the joy of new life” – but the incarnation of the Logos, the second person of the Holy Trinity, the Theanthropos, “begotten of His father before all ages”, for which St. John’s Gospel and the Nicene Creed jointly provide profound insight.

Memorial Prayers for King Michael at Bournemouth

On Sunday, 17 December, following the Divine Liturgy at the Church of Christ the Saviour in Winton, Bournemouth, Memorial Prayers were said for the repose of the late King Michael I of Roumania, who died on 5 December, aged 96 years. Abba Seraphim, who presided at the service, spoke warmly of the late king’s character and the fact that in times of crisis and political change he had remained a constant and faithful monarch and had been widely regarded as a symbol of morality and committed service to his people. Although his reign (1927-1930 & 1940-1947) had ended with the abolition of the Roumanian monarchy, his legacy of peace by effecting Roumania’s withdrawal from the Axcis Alliance during World War II, undoubtedly saved many lives. The presence of the Prince of Wales at his funeral the previous day in Bucharest, which was attended by tens of thousands of mourners, highlighted the affectionate respect of the United Kingdom. Abba Seraphim felt privileged to lead prayers for the late King in solidarity with devout Roumanians who worship at the Bournemouth Church.

The Glastonbury Review resumes publication

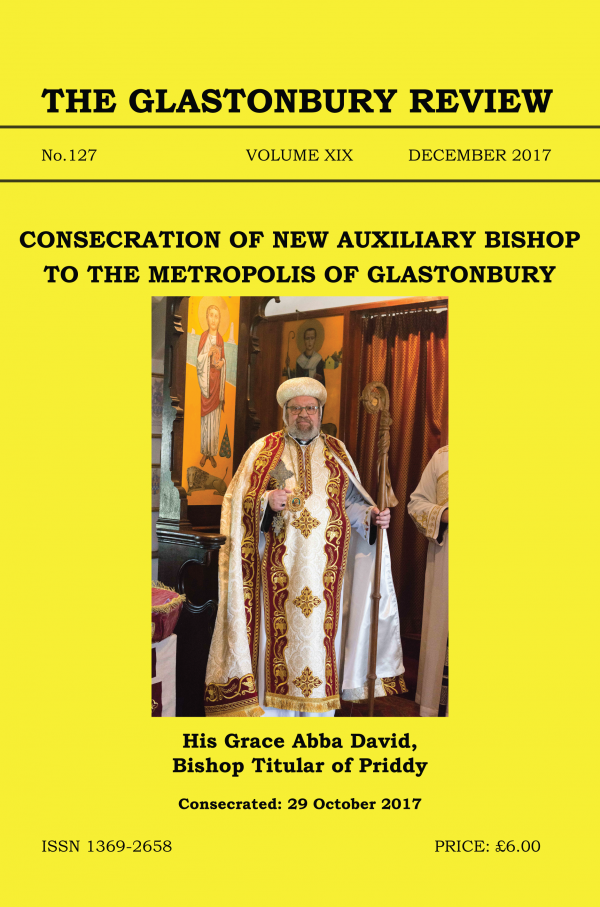

Issue No. 127 (November 2017) of the Glastonbury Review has just been published. The previous issue was published in 2015, but after a gap necessitated by the changes consequent upon the resumption of the independence of the British Orthodox Church, we are happy to resume publication. The front and back covers carry colour photographs of the recent consecration of Abba David as an Auxiliary to the See of Glastonbury, as well as detailed reports inside.

The front and back covers contain coloured photographs of the recent consecration of Abba David as Auxiliary to the See of Glastonbury as well as detailed reports inside. The editorial (“The Same Journey, but different paths”) outlines the changes in our canonical position and our vision for the future and there is quite an extensive “Here, There & Everywhere” section chronicling key items of news since the last issue and reports in the Oriental Orthodox Church News section. Among the articles is one on the Sprotbrough Anchoresses by Father Alexis Raphael; a report of visits to the monasteries between Asuit & Sohag by Lady Coke,; “Lewis Carroll in Holy Russia” and a new feature, “Abba Seraphim’s Question Box” based on recent correspondence. The Book Review section has a number of interesting new publications, whilst the obituaries include the late Tasoni Effa, Metropolitan Kyrillos of Milan and Bishop Geoffrey Rowell.

Copies can bed obtained directly from LULU: http://www.lulu.com/shop/abba-seraphim-editor/the-glastonbury-review-no-127/paperback/product-23437314.html

Protecting the Sheepfold

John X: 1-16

Homily preached by Metropolitan Seraphim of Glastonbury at the Episcopal Consecration of His Grace Abba David, Bishop Titular of Priddy

The image of our Lord as the Good Shepherd is a very ancient one in Christian iconography, where He is depicted as a beardless youth carrying a lamb around his neck. However, whilst the good shepherd image also appears in classical pagan art, where the same figure represents benevolence and philanthropy, for early Christians – forced to elude discovery by their persecutors – it immediately resonated with our Lord’s proclamation of himself as the “good shepherd” in today’s Gospel as well as with John the Forerunner’s proclamation of the “Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world” (John I: 29).

Today’s Gospel extract, however, begins with our Lord’s warning against false shepherds, which He does by making contrasts between the true or good shepherd and the imposter, whom He stigmatises as a stranger, a thief, a robber and a hireling. The true shepherd enters by the door of the sheepfold, which the gatekeeper opens for him, he knows his sheep by name and the sheep follow him because they know his voice. The false shepherd, by contrast, “climbs in by another way”, and the sheep, rather than follow, will flee from him.

How are we to interpret this figurative language. The Gospel tells us that when the Lord spoke in this way “they did not understand what he was saying to them.”

The first thing we might want to note is that these sheep are well maintained, being gathered into a sheepfold rather than allowed to wander and go astray. The pen or fold might be constructed of dry stone walls, or fencing and sometimes simply of thorn bushes but always with a single door, which the shepherd himself guarded, so when our Lords says, “I am the door of the sheep” we know exactly what he means. The purpose is solely protective because sheep are highly vulnerable. They have small brains, poor eyesight and hearing and no defensive devices like teeth, claws or scales. They tend to run in panic when scared, follow the sheep in front of them without caring where it is going and if there is a ditch into which they might fall, a river in which they might drown or a thorn bush in which they might become entangled, they are pretty good at finding it.

The fathers of the Church are in agreement that the sheepfold is an image of the Christian church, though they differ slightly in their interpretation of the door. St. John Chrysostom refers to the door as the Scriptures

“For they bring us to God and open to us the knowledge of God. They make us his sheep. They guard us and do not let the wolves come in after us. For Scripture, like some sure door, bars the passage against heretics, placing us in a state of safety as to all that we desire and not allowing us to wander. And, if we do not undo Scripture, we shall not easily be conquered by our enemies.”[1]

St. Augustine of Hippo argues that Christ Himself is the doorman, the door and the shepherd,

“For what is the door ? The way of entrance. Who is the doorkeeper ? He who opens it. Who then, is he that opens himself, but he who reveals himself to sight ? … If you seek another person for doorman, take the Holy Spirit … of whom our Lord below said, ‘He will guide you into all truth.’ What is the door ? Christ. What is Christ ? The truth. Who opens the door but the one who will guide you into all truth ?” [2]

When I first visited a traditional Egyptian desert monastery and was shown the sturdy Kasr, or fortress, which dominate these ancient habitations, I noted that the original entrance was not by a door in the wall but by a hole in the floor by which visitors were winched up one at a time. Being more familiar with mediaeval English castles I observed that it was also a good vantage point from which to repel invaders with stones, rocks and boiling oil, but was reminded by the rather shocked monk that the monastic fortress was only defensive. The same can be said for the sheepfold.

So, if we follow the analogy of the church and the sheepfold we must recognise that we are the sheep – not a very flattering image, but one which we recognise as apt – and we are highly vulnerable. (Isaiah LIII: 6) reminds us that, “All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned – every one – to his own way.” So what is it from which we need protecting ? In verse one our Lord has already mentioned “thieves and robbers” – basically rustlers – and in verse 12 he mentions the wolves. Added to which is our natural propensity to wander off and get into life-threatening situations. Clement of Alexandria makes the analogy more specific,

“These are rapacious wolves hidden in sheepskins, human traffickers, and opportunistic soul seducers, secretly, but [later] proved to be robbers. They strive by fraud and force to catch us who are unsophisticated and have less power of speech.”

I particularly like that expression, “opportunistic soul seducers” because it emphasises the spiritual nature of our plight, of the need to protect us from the dangers to the soul.

The rustler is intent on stealing us away from the good shepherd solely for his own purpose and profit. We can expect nothing from one who is dishonest and puts his own gratification first. The wolf seeks to devour us. He will show us no mercy, his only intent is our destruction. Compare these to the good shepherd who will actually lay down his life for his sheep. It is hardly surprising that St.Philip, when instructing the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts VIII: 32) uses Isaiah’s prophecy (LIII: 7) about the Christ,

“He was led as a sheep to the slaughter; and like a lamb dumb before his shearer, so opened he not his mouth.”

The great hymnographer, St. Ephraim the Syrian proclaims,

“Blessed be the Shepherd Who became a lamb for our reconciliation.[3]

From earliest times the Church has seen the bishop as the ikon of Christ and used this pastoral symbolism to describe his role. He is a shepherd of souls; one who has the spiritual oversight over a company or body of Christians, as bishop, priest or minister – hence his designation as pastor’, from the Latin word for shepherd and its related word, pascere, ‘to feed’ whilst those under his spiritual care are appropriately designated as his ‘flock’. In the Western tradition the pastoral staff of the bishop is modelled on the shepherd’s crook and in both the Catholic and Byzantine traditions the bishops wear a long white scarf over his vestments known as the pallium or omophorion, symbolising their carrying the sheep on their shoulders. In Rome two lambs are presented to the Pope on the Feast of Saint Agnes (Agnus is the Latin for ‘lamb’), from whose wool the pallia are subsequently made. In the Byzantine tradition it is usual to speak of belonging to the diocese of a bishop, by using the expression of “coming under his omophor”, or pastoral protection.

The great fourth-century biblical scholar, Origen, noting the proclamation of the Lord’s nativity to shepherds, writes,

“Listen, shepherds of the churches ! Listen, God’s shepherds ! … For, unless that Shepherd comes, the shepherds of the churches will be unable to guard the flock well. Their custody is weak, unless Christ pastures and guards along with them. We read in the apostle: ‘We are co-workers with God.’ A good shepherd, who imitates the good Shepherd, is a co-worker with God and Christ. He is a good shepherd precisely because he has the best Shepherd with him, pasturing his sheep along with him.”[4]

England’s Venerable Bede draws another parallel,

“The shepherds did not keep silent about the hidden mysteries that they had come to know by divine influence. They told whomever they could. Spiritual shepherds in the church are appointed especially for this, that they may proclaim the mysteries of the Word of God and that they may show to their listeners that the marvels which they had learned in the Scriptures are to be marvelled at.”[5]

You will notice that the Lord contrasts himself with the “hireling”, a contemptuous expression for someone who makes reward or material remuneration the motive of his actions; a mercenary. He is the wolf in sheep’s clothing, whereas our Lord’s example, as St. Clement reminds us, is of a shepherd in sheep’s clothing.

However, it took the great Saint Cyril of Alexandria to expound this simple pastoral analogy and showing its cosmic significance with the greatest clarity and spiritual insight,

“Humanity, having yielded to an inclination for sin, wandered away from love toward God. On this account we were banished from the sacred and divine fold, I mean the realm of paradise. Having been weakened by this calamity, we became the prey of two bitter and merciless wolves: namely the devil who had beguiled humanity to sin; and death, which had been born of sin. But when Christ was announced as the good Shepherd over all, in the struggle with this pair of wild and terrible beasts, he laid down his life for us. He endured the cross for our sakes that by death he might destroy death.”

We often overlook the rigors and hardship which the good shepherd has to endure in order to tend his sheep, whilst our Lord’s parable of the Lost Sheep (Luke XV: 3-7 and Matthew XVIII: 10-14) demonstrates the infinite pains to which a good shepherd will go to save his sheep. Indeed, I recall once reading a sad report of youngsters who had drowned while trying to save their pet dog. We know the extent to which a caring heart will go to try to save an animal from destruction: how much more a loving Saviour.

Consecration of Bishop David of Priddy

The scheduled episcopal consecration of Father David Seeds was an historic event in the history of the British Orthodox Church. The last consecration of an Auxiliary bishop for the See of Glastonbury had been the late Bishop John (Peace) of Wirral (1923-1990), who was consecrated by Abba Seraphim in 1981 but retired from active ministry in 1986. Since the death of the late Bishop Ignatius Peter (Smethurst) of Priddy (1921-1993), who served from his consecration by Metropolitan Georgius in 1966 until his death in June 1993, Abba Seraphim has been the sole Bishop of the British Orthodox Church.

The preliminary service for the consecration of Father David Seeds began on Saturday afternoon, 28 October at St. Mark & St. Hubert’s Orthodox Church in Cusworth Village. Supported by the two presenting priests, Fathers Antony Westwood and James Maskery, Father David was brought before Metropolitan Seraphim for The Office of the Examen, at which the Protocol of his election with its confirmation and the Apostolic Mandate were publicly read. Following this formality, the Bishop-Elect made the three traditional Professions of Faith, responded to the Interrogatories relating to his purpose, resolution and engagement concerning the duties of the episcopate; and swore the Oath of Canonical Obedience, before making a General Confession and receiving Absolution. Following a short break, Bishop-Elect David then made his monastic profession and was admitted to the monastic brotherhood by Abba Seraphim, following which was held the Office of the Raising of Evening Incense. These services were well attended by local church members, who had come to support their much-loved parish priest.

The following morning, Sunday, 29 October, during the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, and in the presence of a full congregation, enlarged by the Bishop-elect’s friends and former congregation from Derbyshire, the Rite of Episcopal Consecration, according to the Alexandrian tradition, took place prior to the Reading of the Holy Gospel, with Fathers Antony and James supporting and Deacon Athanasius Hall acting as coadjutor to Archdeacon Mark. As Primate of the British Orthodox Church, Abba Seraphim, acting solus, performed the consecration through the laying-on-of hands with prayer and the vesting of the new bishop. He then preached a homily on the Gospel text taken from John X: 1-16.

The new bishop then concelebrated the Divine Liturgy with Abba Seraphim and the priests, and administered the Lord’s Body to the communicants, before receiving the Divine Breath from Abba Seraphim. A particular feature of the Alexandrian Ordination Rite is that after receiving the Precious Blood, and before he drinks from the dismissal water the bishop gives the new priest or bishop the breath of the Holy Spirit, saying “Receive the Holy Spirit” in emulation of the words our Lord spoke to His disciples when he breathed on them and said to them, “Receive ye the Holy Ghost. Whose soever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them; and whose soever sins ye retain, they are retained” (John XX: 22-23). Some ancient liturgical commentaries say the bishop addresses the ordinand with the words of Psalm LXXXI: 10, “Open thy mouth wide and I will fill it”, to which the priest responds, “I opened my mouth and panted” (Psalm CXIX:131), and opens his mouth so the bishop breathes into it the breath of the Holy Spirit and repeats these words and this breath three times. The breath of the Holy Spirit is used by the priest in all the Sacramental prayers and other prayers, such as praying over the sick, or blessing holy oil or water.

At the conclusion of the Divine Liturgy, Abba Seraphim read the traditional Injunction to the new bishop before enthroning him under the name, title and style of ‘His Grace Abba David, Bishop Titular of Priddy and Auxiliary to the Metropolitical and Primatial See of Glastonbury’. He was then invested with the Priddy Crozier, made for the late Bishop Ignatius Peter of Priddy in 1989 and other episcopal regalia, before receiving the congratulations of the congregation and conferring his blessing, whilst seated on the throne.

Following the Liturgy, a reception followed in the Battie-Wrightson Memorial Hall, of traditional Yorkshire steak pies with mushy peas (‘Yorkshire caviar’) and Abba David made a speech expressing his heartfelt gratitude to everyone who had made this such a memorable occasion.

Special thank you to our photographer Mat Dale : http://www.matdalephoto.com/