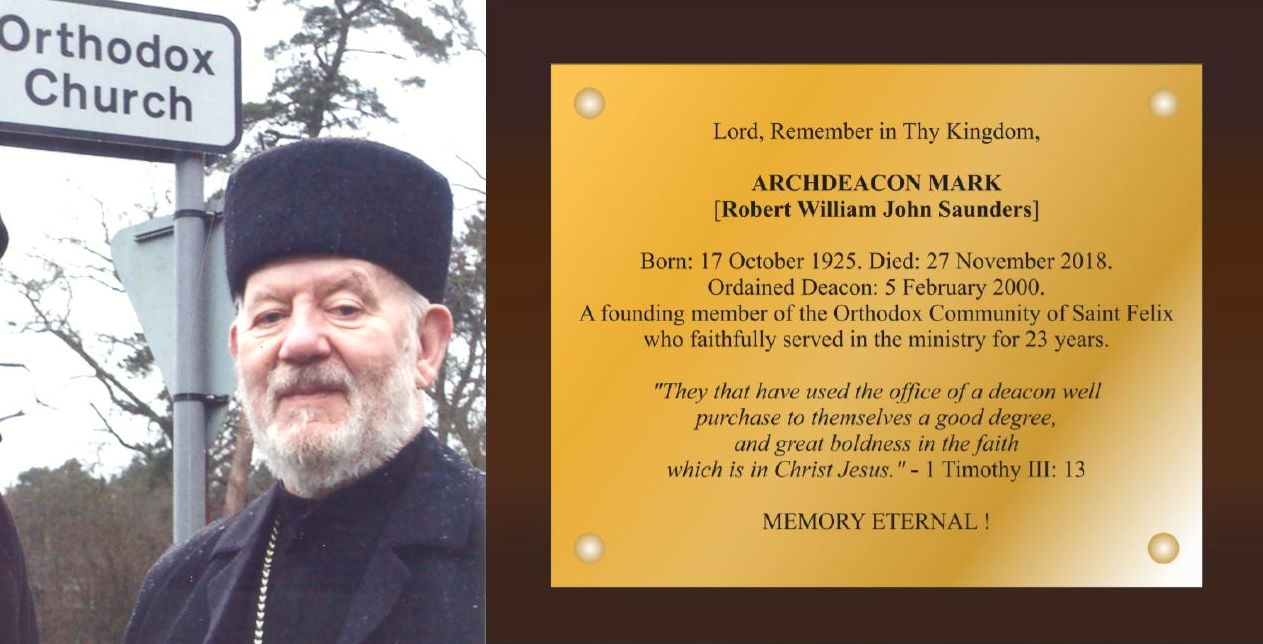

Memorial Brass erected in commoration of Archdeacon Mark

On Sunday, 7 April, following the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, a brass memorial tablet was erected on the inside wall of St. Mary & St. Felix British Orthodox Church at Babingley to the memory of the late Archdeacon Mark Saunders. Although Archdeacon Mark and his late wife are both buried in the churchyard, with an inscribed stone marking their joint grave, Abba Seraphim felt that it was both desirable and appropriate to also have a memorial inside the church. The tablet records Archdeacon Mark’s many years of ministerial service as well as the fact that he was a founder of the Orthodox community of St. Felix in Norfolk. The memorial plaque’s presence serves as a reminder to worshippers to pray for the repose of Archdeacon Mark. Also, as the clergy process around the church during the Raising of Morning & Evening Incense to gather up the prayers of the worshippers, along with invoking the prayers of the saints whose ikons are hung on the church walls, they also unite their prayers with the faithful departed who repose in the Saviour’s bosom in Paradise. The regular worshippers at St. Felix were joined by some members of Archdeacon Mark’s family, who were warmly welcomed by Abba Seraphim and Abba James.

The funeral of His Beatitude Mesrob II, Armenian Apostolic Patriarch of Istanbul

The following account was written by Father John Whooley, one of Patriarch Mesrob’s former teachers, who attended the funeral.

The death of Patriarch Mesrob Mutafyan at the age of 62 occurred on Friday, 8 March. His demise at Istanbul’s Armenian Hospital of Sourp Pirgich finally brought to a close almost ten years of an illness, the cause of which is still a matter of debate among members of his community. The last few years of that illness had witnessed a complete breakdown of any recognition by him either of his surroundings or even of those who had been closest to him. His mother, who attended him almost constantly, was the foremost observer to suffer the consequences of this development. Her son, from an individual who had shown such exceptional qualities of leadership, even before his election as patriarch in 1998, and especially so with young people, to one who was then deprived of any awareness of who he was or where he was, this was indeed a tragic development, for himself, for her, and for his community. As recovery became even more remote, his death could be seen as a release.

Patriarch Mesrob, wearing his robes and mitre, was placed in an open coffin within his patriarchal Cathedral of the Holy Mother of God in Kumkapi. There the faithful were able to pay their respects on the afternoons of Thursday and Friday following his death. At each corner of the bier and facing inwards were priests in copes who recited prayers for the departed. It was to be on Sunday, 17 March, that the final Liturgy was to be celebrated, to be followed by burial in the Armenian Apostolic cemetery in Shishli.

Offices of the Dead began on the morning of the appointed day at 7.30, leading to the central celebration, the Badarak, at 10 o’clock, at which time most of the higher prelates and clergy were seen to arrive. A notable presence was that of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Nourhan Manougian. The main celebrant was one of the three representatives of the Catholicos of Etchmiadzin, Karekin II, the other two being Archbishop Sebouh Chouljian and Archbishop Khajag Barsamian. Two archbishops represented the Catholicosate of Cilicia, including Archbishop Nareg Alemezian. Archbishop Aram Ateshian and Bishop Sahag Marshalyan, both of the Patriarchate of Istanbul, were also present, along with virtually all the local Armenian Apostolic clergy.

Two clergy of the Ecumenical Patriarchate were present as well as Archbishop Yusef Chetin, who represented the Syrian Orthodox community. The Armenian Catholic Archbishop of Istanbul, Levon Zekiyan, represented the Armenian Catholics of the city, while the Vicar Apostolic of Istanbul, Bishop Ruben Tierrablanca Gonzalez, represented the Latin Catholics. Also present were the leaders of the Syrian and Chaldean Catholic communities. The Papal Nuncio to Ankara sent a representative, whilst the French Dominican, Hyacinthe Destivelle, represented the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. Also from Rome, was a member of the Community of Sant ’Egidio, Mgr. Marcvo Gnavi. In the same quarter of the Chancel was to be found the Chief Rabbi of Turkey, Ishak Haleva.

In the left area of the Chancel, in the vicinity of the patriarchal throne, itself draped in black, were seated various Turkish local political figures, along with lay leaders of the Armenian community.

The singing of the Gospel concluded, various addresses were given in Armenian and in Turkish, concerning the achievements of Patriarch Mesrob, with special mention of his ecumenical interests.

One of the most moving episodes, after the coffin was transported up onto the very sanctuary itself, was the anointing of the former 84th Patriarch of the city by all the participating prelates, this ceremony being led by Patriarch Manougian. The full ensemble of the Armenian clergy, including the various grades of altar assistants, then paid their respects.

At the conclusion of the Liturgy, the Patriarch was borne out of his Cathedral, with pauses for prayers and intercessions. He was then placed in front of the Patriarchate itself, within its gates. A large crowd listened to messages of appreciation read from the steps of the building, including one from Pope Francis. Further prayers were offered, after which the move to the Shishli cemetery began, where further numbers of the faithful were already in attendance. Without delay, the patriarch was carried to that portion of the grounds where his predecessors were buried, his own grave being next to that of Karekin II Kazanjian. A crush ensued around the place of burial as further prayers were offered for the repose of the departed; crowd pleasure increased when soil was distributed to be added to that already covering the patriarch’s remains.

Most fortunately, throughout these days of farewell to such a gifted leader, lost too soon through debilitating illness, the weather proved itself at its most accommodating, with clear skies and warm sunshine, reflecting earlier and happier times in the life of Mesrob II, Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul.

May he rest in the peace of Christ !

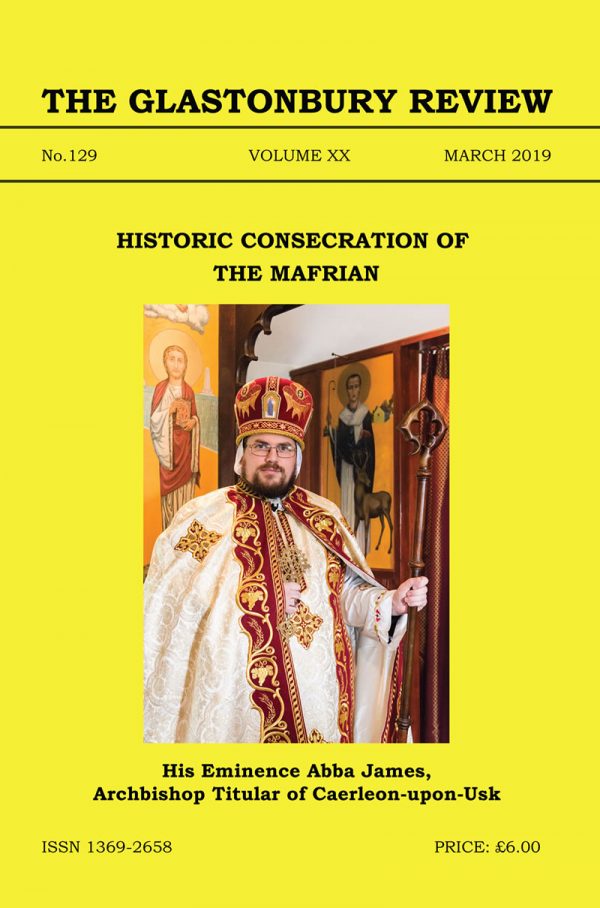

Latest issue of The Glastonbury Review just published.

Issue No. 129 (March 2019) of the Glastonbury Review has just been published. This issue is 128 pages. The front and back covers carry pictures taken at the historic episcopal consecration of Abba James as the new Mafrian: the Perpetual Coadjutor of the Metropolis of Glastonbury, which is reported in detail in the “Here, There & Everywhere”, along with key items of news since the last issue. The “Oriental Orthodox Church News” section contains an update detailed report of the trial of the two monks found guilty of the murder of Bishop Epiphanius, the Abbot of St. Makarius monastery with reviews of press comments suggesting that the murder might have been linked to contemporary church policies. As 2019 marks the fortieth anniversary of the death of Metropolitan Georgius and the succession of Abba Seraphim, an article Forty Years Ago records detailed church events at that time with some previously unpublished historic photographs; whilst an earlier article An Important Anniversary for British Orthodoxy written in 1997 by the late Father Gregory Tillett, offers an historical insight on recent past history.

Among the articles is a theological one by Abba Seraphim on Divine and Human. In the Likeness of Christ, whilst he has also written another The Letter Killeth, but the Spirit giveth Life addressing the issue of the misuse of canonicity and Phyletism with reference to contemporary church issues, such as the problems of the Russian Exarchate under the Oecumenical Patriarchate and the divisions caused by the recent grant of autokephaly to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. There is also the text of one of Abba Seraphim’s homilies on Luke XII: 1, “Beware the Leaven of the Pharisees, which is Hypocrisy.”

The ‘Book Review’ section includes Abba Seraphim’s latest book As Far as the East is from the West. Sidelights on Assyrian Church History and Martin Mosebach’s tragic but informative account of the 21 Neo-Coptic martyrs murdered in Libya in 2015 by Isis. This issue concludes with lengthy obituaries of Archdeacon Mark Saunders of the Babingley Church; Vanessa Tinker, Principal of the Glastonbury School of Ikonographer and Father Gregory Tillett, of Sydney, Australia.

Copies can be obtained directly from www.Lulu.com

Death of Patriarch Mesrob II of Constantinople

On 8 March 2019 Patriarch Mesrob II Mutafyan, Armenian Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople, died at the age of 62.

Minas Mutafyan was born in Istanbul on 16 June 1956. He studied at Memphis University, USA. 1974-1979, during which time he was ordained deacon in 1977 and as priest on 13 May 1979. He studied at the Patriarchal Seminary & Hebrew University at Jerusalem: 1979-1981, before returning to Turkey, where he served as parish priest for Kinali 1982-1986, and was elevated as vardapet in 1983 and Dzairaguin vardapet in 1986. He was a protégé of Shnork I Kaloustian (1913-1990), the 82nd Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople. On 21 September 1986 he was consecrated to the episcopate at Etchmiadzin and served as Chancellor of the Patriarchate as well as Coordinator of Ecumenical Relations. In 1993 he was created Archbishop of the Princes Islands by Patriarch Karekin Kazanjian (1927-1998) and because of Patriarch Karekin’s failing health he soon acted as Vicar-General and locum tenens until his own election as Patriarch on 14 October 1998.

Abba Seraphim first met Archbishop Mesrob in April 1997 when he attended a reception at the Armenian Patriarchate in Kumkapi to welcome Patriarch Karekin II back on his return from attending the Holy Synod in Etchmiadzin and they soon became firm friends, which led to Abba Seraphim becoming a frequent visitor to Istanbul, accompanying the Armenian clergy on local pilgrimages and other special events, during which he got to know the local clergy very well as well as Patriarch Mesrob’s mother. Abba Seraphim attended and participated in Patriarch Mesrob’s enthronement in October 1998. For some period his advice was also sought on improving English texts of key press releases and translations of other important documents.

Patriarch Mesrob was not only a highly educated theologian, with a keen sense of church history -which he shared with Abba Seraphim – but he was a dynamic and deeply pastoral church leader and there was great hope that the Armenian Church as a whole would benefit from his leadership, especially as he worked closely and constructively with the Catholicoi of Etchmiadzin and Cilicia, with his brother Patriarch of Jerusalem, the Anglophile Torkom Manoogian, and with the Oecumenical Patriarch.

In 2008, however, he became unwell – which was frustrating for someone so full of energy and vision. He was eventually diagnosed with fronto-temporal dementia (Pick’s disease) and within only a few weeks his condition rapidly deteriorated, so that for the past decade he has been in a totally comatose condition. Out of respect and deep affection the British Orthodox Church has kept him in their prayers and Abba Seraphim has now directed that the full traditional forty days of mourning should be observed.

On Sunday, 10 March Abba Seraphim and Abba James led memorial prayers for Patriarch Mesrob at the Church in Chatham.

Patriarch Mesrob: Memory Eternal !

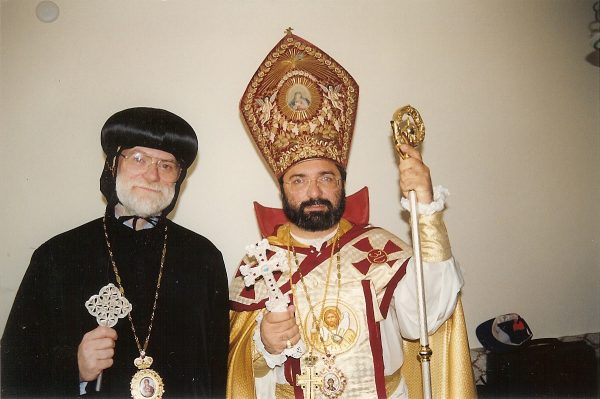

Historic Consecration of the Mafrian

The elevation of Father James to the episcopate is a very significant event in the history of the British Orthodox Church. The last time this happened was in 1977 when Abba Seraphim was consecrated to the same titular see with the purpose of becoming the coadjutor to the late Mar Georgius.

Abba James’ service to the church

Abba James, was born at Ashton-in Makerfield, Lancashire, on 15 July 1984, where his family had lived since 1800. Soon after his parents moved to Leeds, where he attended school and in 1993, when they moved to Surrey, he studied Computer Science at Brooklands College at Weybridge. His early involvement with the church was through his technical support for its online presence and the development of the Church websites. Following his graduation from Southampton Solent University he moved to London in July 2006 and stayed temporarily at the Church Secretariat at Charlton. Having proved himself invaluable in a number of fields, he then served as Abba Seraphim’s chauffeur and also as Church Treasurer in 2006-2009, following which in 2008 he was appointed a lay Trustee and PA to Abba Seraphim, taking up permanent residence at the Secretariat.

During his time as a catechumen he visited Egypt in 2009 and met Pope Shenouda; he also accompanied Abba Seraphim to Malabar in January 2010, to the Eritrean Community in New York in July 2010 (where he addressed the Eritrean Orthodox clergy about the website he had created for their imprisoned Patriarch, Abune Antonios and the importance of harnessing the power of the internet), to Malta in April 2011 and to the Phanar in Istanbul in July 2012, where he met the Oecumenical Patriarch.

He was finally received into the British Orthodox Church through his baptism and chrismation on 30 June, 2012. He was ordained Reader at St. Alban’s Church, Chatham, Kent, on 11 November, 2012; Subdeacon at St. George-in-the-East, Shadwell, London, on 12 January, 2014; Deacon at the Church of St. Mark & St. Hubert, Cusworth, on 6 December, 2015; Archdeacon at Cusworth on 1 May, 2016; Priest at Cusworth on 30 July 2017; Hegoumenos at the Church of Christ the Saviour, Bournemouth, on 16 December, 2018 and on 22 December, 2018 at Christ the Saviour he received the first Monastic Tonsure according to the Order for a Beginner taking the Rason and was received into the Brotherhood of Monks.

Office of the Examen

The consecration service was preceded on Friday, 22 February by the Office of the Examen, during which the Instrument of Nomination as Mafrian, with its confirmation and the Apostolic Mandate were publicly read by Archdeacon Antony Holland; the Bishop-Elect made the three solemn Professions of Faith and responded to the Interrogatories relating to his purpose, resolution and engagement concerning the duties of the episcopate, followed by his swearing the Oath of Canonical Obedience, before making a General Confession and receiving absolution.

Ecumenical Guest

Among those invited to attend the Consecration Liturgy as an ecumenical guest, was Mgr. Douglas Titus Lewins, Archbishop Titular of Lindisfarne & Primate of the Old Roman Catholic Church in Great Britain. In welcoming him, Abba Seraphim noted that the late Patriarch Georgius had been on personally friendly terms with the late Archbishops Bernard Mary Williams (1889-1952) and Geoffrey Paget King (1917-1991); whilst Abba Seraphim had also been a good friend of the late Archbishops James Hedley Thatcher (1921-1996) and Dennis St. Pierre (1932-1993). Archbishop Douglas, who has been a friend of the British Orthodox Church for many years, also holds firmly to the Orthodox Faith recognised by the two Acts of Union under Archbishop Arnold Harris Mathew with the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch on 5 August 1911 and with the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria on 26 February 1912.

Consecration to the Episcopate

On Saturday morning, 23 February, following the office of the Raising of Morning Incense, Father James was led into the church for his consecration. In keeping with the ancient Coptic tradition his hands were held by two bishops to prevent him from escaping from the responsibility of the episcopate. Abba David of Priddy was on one side, whilst on the other was Archbishop Douglas.

The ceremony of consecration took place following the Praxis and the congregation all joined in saluting the new Bishop with the traditional greeting, Axios! Following the laying on of hands by Abba Seraphim, assisted by Abba David, Archbishop Douglas also conferred a special blessing on the new Archbishop, after which Abba James was vested in his episcopal regalia and then concelebrated the Liturgy with Abba Seraphim and Abba David. Before assisting Abba David in communicating the congregation, Abba James received the ‘Holy Breath’ from Abba Seraphim.

At the end of the Divine Liturgy, Abba Seraphim read the traditional injunction to a new Bishop before enthroning him under the name, title and style of ‘His Eminence Abba James, Archbishop Titular of Caerleon-upon-Usk and Mafrian (perpetual coadjutor cum jure successionis) to the Metropolis of Glastonbury and British Patriarchate’. He was then invested with the pastoral staff of the late Bishop Mar Jacobus (Herford), made for him by Indian Christians in 1902 and other episcopal regalia, before receiving the congratulations of the congregation as he distributed the antidoran to them.

Following the Liturgy a reception followed in the Battie-Wrightson Memorial Hall, at which all present at the service joined in.

Photos provided by Mat Dale https://www.matdalephoto.com/