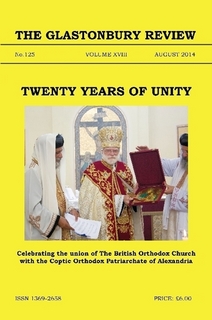

Twenty Years Of Unity

Twenty years ago the British Orthodox Church in its present form came into being. It had already existed as a church for more than twelve decades, but for almost all that time it had been outside the canonical structures that define Orthodox ecclesiology and its hierarchs had played no part in the wider witness of the Church. However, it traced its origins to the Syrian Orthodox Church in the 19th century and its leaders sought a return to their Oriental Orthodox roots.

Through the grace of God the approach was to the late Pope Shenouda, one of the most outstanding Orthodox hierarchs of the twentieth century. Although himself deeply rooted in the rich heritage of Coptic Egypt, he was able to comprehend the desire of Christians of ancient Western nations seeking to return to the Orthodox Faith, whilst preserving their local character and diversity of traditions nurtured within different historical experiences. The Coptic Church had always respected the unique character of Ethiopia’s Orthodoxy, whilst its more recent outreach to other African nations had embraced those cultural and historical differences which were not alien to Orthodoxy.

At the recent Thanksgiving Service marking this anniversary, Abba Seraphim made a very clear statement of the raison d’être of the British Orthodox Church, when he stated that it is “in fulfilment of the church’s catholicity” that it “exists to preach that apostolic tradition of the gospel to the British people.” Whilst few people find it difficult to recognise the universality of the witness of the Roman Catholic Church, there is still a tendency to regard Orthodox as ‘foreign’ or ‘exotic’ and restricted to ministry in Eastern Europe or the Middle East. Yet the same universality of witness belongs to Orthodoxy as to Catholicism even though the vicissitudes of history have limited its geographical influence. In 1874, Father Stephen Hatherly, an English priest of the Greek Church, considering how the Orthodox Church had providentially survived the great external calamities of history, wrote:

“Then suddenly, as sea that burst its bounds, the Orthodox Faith overflowed and spread itself over the boundless tracts of Russia ….and may now count her children from the shores of the Adriatic to the bays of the Eastern ocean on the coast of America, from the icefields which grind against the Solovetsky Monastery on its savage islet in the North to the heart of the Arabian and Egyptian deserts.” [1]

Had Father Stephen included the ancient Oriental Orthodox churches his scope might also have comprehended Orthodox Christians from the ‘Mountains of the Moon’, where the Scotsman, James Bruce (1730-1794) stumbled across the Ethiopian Orthodox in his search for the source of the Nile; or the officers of the East India Company and the Royal Navy, who, whilst exploring the Coramandel Coast, encountered the ancient Syriac communities of Malabar.

There is, however, a distinction to be made between British Orthodoxy and other Orthodox churches ministering here in these islands, which Abba Seraphim highlighted when he said, “It is not part of a diaspora ministry from a mother church elsewhere, but the implanted seed from those ancient Christian churches which have faithfully preserved their heritage through centuries of persecution and hardship.” It is for this reason that we are not Copts, although we cherish and embrace the history, traditions and spirituality of our Mother Church. Just as a child may feel a profound love for an adopted parent who, out of selfless devotion and consumed by zealous tenderness, extends the same maternal care to all her children, whether they are of her flesh or not; so we too regard the See of Alexandria with filial thankfulness and respect.

Article 1 of the 1994 Protocol determining the Relationship of the British Orthodox Church to the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, signed by Pope Shenouda III and Abba Seraphim states:

“The British Orthodox Church of the British Isles is a local church, holding to the historic faith and order of the Apostolic Church, committed to the restoration of Orthodoxy among the indigenous population and desiring to provide a powerful witness to the Orthodox Faith and Tradition in an increasingly secular society.”

Over several decades the various Orthodox jurisdictions established in the British Isles have undergone significant changes in their membership as second and third generation faithful have become increasingly indigenised and converts from other faiths, or none, have joined their ranks. This has also been matched by a serious leakage of younger members, to whom commitment to an ancestral religion seems less compelling than identification with the secular culture of the surrounding society. Added to this have been the predatory inroads made by Protestant and Pentecostal sectaries offering what appears to be a more vibrant and demanding faith to those only loosely attached to Orthodoxy, but is really a danger and delusion. In the face of these challenges, the response of the clergy has been mixed, some committing themselves to active ministry to youth and challenging the proselytisers, some adopting their opponents’ tactics and spirituality in the false belief that it will stem the haemorrhage, whilst others simply refuse the confrontation and continue ministering to those who still remain faithful.

As this is a common challenge to all our Orthodox communities, regardless of their ethnic origin, it is one which needs to be addressed together. Here and there different jurisdictions organise regular camps and conferences for their Youth but seldom do we see the co-operation between different ethnicities and traditions on a pan-Orthodox level, transcending the petty divides of culture and language in a witness to their shared faith. As our hierarchs meet together in fraternal dialogue and talk of Orthodox unity, why is the manifestation of that unity on the ground still so fragmented and lack-lustre ? The talk of Orthodox unity is not matched by the reality. Even among the Eastern Orthodox Churches in Great Britain, whose hierarchs, since June 2010, have begun regular meetings as the ‘Pan-Orthodox Assembly of Bishops with churches in the British Isles’, a cross-jurisdictional structure has been established, though its impact is yet to be manifested. Sadly, the Council of Oriental Orthodox Churches remains simply a fraternal fellowship with no inter-church structures.

In the lands of the dispersion the canonical order of one bishop in each city is totally disregarded and each Orthodox hierarch presides over the churches of his own ethnicity almost as if they are distinct denominations. Generally the bishops adopt titular sees from their mother country often adding “of Great Britain” as an addition to their title.

Where, we may ask, is the desire to see the manifestation of a truly ‘local’ church, whose catholicity is not manifested in the ethnicity or racial origins of her members, but because she manifests herself through the fullness of faith, where there is neither Greek nor Jew, because the Gospel is preached to all creatures ? The late Father John Meyendorff believed that through narrowly identifying with one ethnic group,

“The Orthodox Church simply lost the very appearance of being the Catholic Church of Christ. It is being seen by all observers as a projection of various immigrant ethnic groups. And, what is even worse, the Orthodox themselves have lost sight of the ‘territorial principle’ … and have ceased to consider it as a norm of church organisation.”[2]

Almost a century and a half ago the Eastern Orthodox Churches, gathered at a Pan-Orthodox Council in Constantinople in 1873, to condemn the heresy of Phyletism,[3] the national or ethnic principle in church organisation, or more specifically defined as the belief “that the Church can be territorially organized on an ethnic, racial, or cultural basis so that within a given geographic territory, there can exist several Church jurisdictions, directing their pastoral care only to the members of specific ethnic groups.”[4] Despite this declaration ethno-phyletism is alive and well today in both families of Orthodoxy and the multiplicity of ethnic jurisdictions existing side by side in “the lands of emigration” stands in direct contradiction to the ecclesial principle of one bishop in each city.

In defining our ministry under the title of ‘The British Orthodox Church’ we do not lay exclusive claim to minister to the people of these lands; nor do we desire to denigrate the rich pastoral service of the Orthodox clergy who have lovingly cared for generations of their exiled countrymen. We do not deny the significant outreach and witness of many who work under an ethnic jurisdiction and we cherish what they have done for us all and gladly embrace it. In strongly asserting that our primary vocation is to live out and proclaim our Orthodox Faith in these British Isles, as our steadfast resolve, we merely reaffirm what is declared in our Protocol with the Alexandrian Patriarchate. The recent Pan-Orthodox Conference at Swanwick, 25-27 July 2014, was largely a lay initiative, supported by the clergy, but with no agenda other than to reach out in love across the jurisdictional divide in shared witness to a common faith. Its low-key approach may have attracted little attention, but through being organised, as well as supported, in equal measure by clergy and faithful of both families of Orthodoxy, it witnessed to and generated, an important message of Orthodox unity.

Faced with the rising tide of secularism in Western Europe, we “who have beheld the true Light … received the heavenly Spirit … and found the true faith”[5] possess a duty to witness to the eternal truths of that faith and to offer the healing balm of Orthodoxy to those who are seeking spiritual sustenance. As Abba Seraphim declared in his address at the Anniversary service,

“In seeking the continuity of faith from the apostolic age, many people find the faith and spirituality of the Orthodox Church fills their emptiness and satisfies their yearning.”

The British Orthodox Church is still a small jurisdiction with limited resources, but is anxious to answer this need in our nation. For two decades – almost a generation – it has quietly consolidated its existing congregations and steadily extended its outreach in preparation for a wider work, during which some of our clergy and faithful have fallen asleep and, through the mercy of God, others have arisen to take their place. Whilst standing on the foundation of the apostolic tradition of Orthodoxy, it lays no claim to an exclusive ministry, but gladly works with and alongside Christians of other traditions in partnership and sharing of those things we hold in common; nor does it seek to profit by the uncertainties of some by seeking to augment its own numbers at the expense of other churches: preferring rather to reach out to those who wander and stumble as spiritual orphans. We pray that Almighty God may continue to pour out his blessings so that we may faithfully fulfil our vocation and that the British Orthodox Church may be a loving co-worker with all who seek to bring truth and mercy, grace and salvation to the people of these lands.

[1] Ancient and Modern Traces of God’s Providential Hand in the History of the Orthodox Church. A Lecture delivered in the Greek Syllogos, Manchester, on Wednesday, October 2nd (14th), 1874, by The Very Reverend S.G. Hatherly, Proto-Presbyter of the Patriarchal Œcumenical Throne (James Bute, Cardiff: 1874), p. 13.

[2] “The Forgotten Principle” in John Meyendorff, Vision of Unity (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, New York: 1987), p. 57.

[3] Vide articles on “The Bulgarian Question” and the 1872 Council of Constantinople by Matthew Namee on the internet site, Orthodoxhistory.org (The Society for Orthodox Church History in the Americas), republished with comments from original articles in The Methodist Quarterly Review, July 1870, April 1871, April 1872, January 1873, July 1873 and April 1874.

[4] Fr. Stephane Bigham, The 1872 Council of Constantinople and Phyletism, Orthodox Christian Laity internet site: www. ocl.org

[5] Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom.