An Introduction To The Liturgy Of Saint James

Antiquity

The pious attribution of apostolic authorship to a text or a liturgy may not be verifiable historically, but it should not be viewed simply as an inept forgery, but rather as implying, at the very least, that the text in question stands firmly in the apostolic tradition which the local church has preserved throughout the generations. The Preface to a Malankara edition of the Syrian Liturgy of St. James describes it as,

“The Anaphora of Mar James, the brother of our Lord. And this is the first Corban, which he said he heard and learned from the mouth of the Lord. And he did not add, and did not omit in it a single word.”[1]

The same faith in its origins is expressed by Bar Salibi (who died in 1173):

“Our tradition is that on the Tuesday after the Descent of the Holy Ghost, the Apostle James performed a liturgy entirely the same as this which we have; and when he was asked whence he received it, he answered, ‘As the Lord liveth, I have added nothing and taken away nothing from that which I heard from our Lord.’ Wherefore this Liturgy is of the highest excellence and first of all.”[2]

Indeed, canon XXXII of the Quinisext Council in Trullo (692), in criticising the Armenians for their lack of a mixed chalice, quoted Saint James as their authority:

“For also James, the brother, according to the flesh of Christ our God, to whom the throne of the Church of Jerusalem first was entrusted, and Basil, the Archbishop of the Church of Cæsarea, whose glory has spread through all the world, when they delivered to us directions for the mystical sacrifice in writing, declared that the holy chalice is consecrated in the Divine Liturgy with water and wine.”

Later writers, especially Protestant polemicists, argued against apostolic authorship, pouring scorn on those who defended it and citing the anachronistic use of more developed theological expressions. In response, scholars of the stature of Cardinals Caesar Baronius (1538-1607), Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) and Jacques Davy du Perron (1556-1618) defended the authorship, whilst admitting that the texts had undergone later additions. The Catholic orientalist, Eusèbe Renaudot (1646 1720), whose Latin translations of early Eastern liturgies, including St. James, first appeared in his Liturgiarum orientalium collectio in 1715-16, suggested that whilst the liturgies may not be the work of the apostles themselves, they rightly bore their name because they were the liturgies of the churches which they had founded.

“The liturgies are not merely the transitory utterance of one man’s opinion, however great or holy or well informed he may have been. True, the opinion of the author merits consideration on account of the dignity, authority, knowledge or ability of him who expresses it. But when all has been said it does no more than commit him to the view as a private person, whereas a liturgy is used for the performance of divine worship, and for the most important act of that worship, the Mass. A liturgy, expressing as it does the official speech of a Church, is, as it were, that Church’s profession of faith. Of it, more particularly, it is true to say that, when hearing it, one is hearing a whole section of the Christian world. The name of its author is of small account, the dignities with which he was invested leave us indifferent, his very knowledge does not affect us; his authority is that of the Church which adopted his text for the exercise of its worship.”[3]

It is very easy to dismiss such devout sentiments as an “antiquated and exploded position”[4] but we should be careful not to lose sight of the reality that at its core the Liturgy of St. James represents an apostolic rite of great antiquity. The distinguished French Catholic scholar, Louis Bouyer (1913-2004), notes that,

“Even if St. James is assuredly not its author, this liturgy represents a Jerusalemite tradition, as is shown by the many allusions to the holy places that it includes, and the role played by the constant evocation of the heavenly Jerusalem.”

The prayer, “Exalt the horn of Christians, through the power of the precious and life-giving Cross, we beseech Thee, O Lord”[5] is believed to be a reference to St. Helena’s invention of the True Cross at Jerusalem in the early fourth century. Similarly the opening words of the Commemoration of the Living indicate their origin, “We offer unto Thee, these Gifts O Lord on behalf of Thy holy places, which Thou hast glorified by the epiphany of Thy Christ and the visitation of Thine all-holy Spirit, and above all for the holy and glorious Sion, the mother of all churches.” Bouyer asserts it “remains the most accomplished literary monument of perhaps the whole of liturgical literature.”[6] Numerous liturgical scholars have spoken of it with profound respect. Canon E.C. Ratcliff (1896-1967), Professor of Liturgical Theology at King’s College, London, described it as of “great beauty” and commended it as a model for worship in the Indian Church, where it became the inspiration for the Bombay Liturgy.[7]

Jerusalem in the fourth century was within the ecclesiastical orbit of Antioch, although its position as the ‘holy city’ gave it an unique status once Constantine showed his support for the church. Canon VII of the first ecumenical Council at Nicaea, recognised the right of the Bishop of Jerusalem to a position of honour, after the Metropolitan of Caesarea. At local synods of the bishops of Palestine, the Bishop of Jerusalem would preside in honour, even though the actual office of Metropolitan of Palestine belonged to the Metropolitan of Caesarea. At that period the liturgy was still evolving and there were local variations. The early roots of the rites used in both Jerusalem and Antioch can clearly be found in the VIIIth book of the Apostolic Constitutions, where the compiler (originally believed to be St. Clement of Rome, hence its designation as the ‘Clementine Liturgy’) – in order to enhance its authority – has retrospectively attributed sections to specific apostles.[8] The Apostolic Constitutions is believed to have originated in Syria, and dates from around 370-380.

Anxious to reconstruct the Liturgy used by St. John Chrysostom himself when he was still at Antioch (386-397), the liturgist Charles Edward Hammond (1837-1924), teased out and rearranged the numerous liturgical references in his published writings to produce The Ancient Liturgy of Antioch, the result leading him to the conclusion that,

“St. Chrysostom used a Liturgy intermediate in form between the Clementine and that of S. James. In elaborateness it equalled St. James’ Liturgy, which it resembles in several minute and verbal particulars; but in its earlier part, in which scarcely anything seems to have preceded the Lections, and which exhibits the full forms of Dismissal, it more nearly approached the Clementine. Conversely, if we are justified in assuming this form for certain to have been the form of St. Chrysostom’s age, we may infer that the Clementine represents a still earlier stage of the Liturgy, and our present St. James a later stage, in which certain additions and alterations had already been made.”[9]

Having made a close comparison between the anaphoras of Basil and James, Dom Gregory Dix (1901-1952) the scholarly Anglican Benedictine, concludes,

“One general inference which seems to impose itself … is that the fourth century Jerusalem rite was fused with the fourth century rite of Antioch to produce the ‘patriarchal’ rite of Antioch (the present St. James) rather by way of addition to the Antiochene local tradition than by way of substitution for it. Considerable fragments of the supposedly ‘lost’ old rite of Antioch are to be found embedded in the present text of St. James.”[10]

Bouyer notes the skilful theological development from the Apostolic Constitutions to the Liturgy of St. James,

“If we look at the Eucharist of St. James as a whole, we are especially struck by the clarity of its Trinitarian theology, which is expressed with much more exacting precision in its structure than could be seen in the liturgy of the 8th book of the Apostolic Constitutions. All the duplications and all the repetitions in thought have been definitively and categorically removed.”[11]

Tarby believes that the simplicity of the Greek text, the absence of theological developments, its freedom in the use of biblical quotations and the asymmetry of formulas all argue for its seniority.

The unique arrangement of the Christian shrines in Jerusalem led to very specific developments at Jerusalem and under St. Cyril we find that the Jerusalem liturgy had become quite distinctive. Ordained deacon by St. Macarius in 335 and priest about 343 by St. Maximus, whom he succeeded as Bishop in 350, St. Cyril served as Bishop of Jerusalem until 386.[12] Cyril’s Mystagogical Catecheses, describes the Eucharistic prayer and provides us with an insight into a key stage in the development of the Hagiopolite liturgy. Dr. Burreson[13] says that Cyril’s testimony “reflects the ecclesiastical conservatism of its bishop, while also displaying the influence of the ecclesiastical centres of Alexandria, Antioch, and Caesarea (Cappadocia). It is a crucial indicator of fourth-century anaphoral developments and of the role of Cyril at the centre of those developments.”[14] Within a few years the Jerusalem liturgy had supplanted the old Antiochian rite and was established as the Patriarchal Rite of Antioch. Dix places this between 397, when St. John Chrysostom left Antioch and 431 “when Bishop Juvenal of Jerusalem greatly embittered relations between Jerusalem and Antioch by claiming not merely independence (which he successfully asserted twenty years later) but jurisdiction over Antioch itself for his own see.”[15]

Quite detailed evidence of the worship of the Church in Jerusalem is also contained in the account by Egeria – a late fourth century pilgrim – of her visit to the East between 381 and 384, when St. Cyril was nearing the end of his long ministry. Although the Jerusalem Church was Greek-dominated at this period, and the liturgical language was Greek, Egeria tells us that there was a Syriac speaking minority whose needs were met:

“In this province there are some people who know both Greek and Syriac, but others know only one or the other. The bishop may know Syriac, but he never uses it. He always speaks in Greek, and has a presbyter beside him who translates the Greek into Syriac, so that everyone can understand what he means.”

Only discovered in 1884, this document indicates that the text of the liturgy was still fluid and there are good reasons for believing that St. Cyril himself may have been responsible for re-ordering the ancient rites. Witvliet[16] describes the Jerusalem redaction as “a theologically astute conflation of Palestinian sources with an early form of the anaphora of St. Basil.”

Liturgical links with Egypt

Liturgy is an area where there has always been a great deal of cross-fertilisation and modern liturgical scholars debate both sources and later influences with a scientific precision not so readily available to earlier generations. Burreson notes that in the first two centuries of the Christian era, Alexandrian Christianity appears to have been heavily dependent on Hagiopolite Christianity. However, after Rome’s destruction of Jerusalem the situation was reversed and Jerusalem owed its theological heritage to Alexandria, particularly Origen. Cyril of Jerusalem was certainly influenced by the Alexandrian theological tradition in his education, presumably in Caesarea (Palestine) and Jerusalem, and probable visits to neighbouring sees during his numerous exiles.

The discovery in Cairo in 1895 by Dr. Agnes Smith Lewis of a Palestinian Syriac lectionary of an Aramaic-speaking community in Egypt led to the conclusion that they had used the Liturgy of St. James[17], although that connection did not go unchallenged.[18]

In making a detailed comparison between St. Cyril’s commentary and the earliest texts of St. James, Dix observes, “There is a curious detail, however, in Cyril’s phrasing which is not taken over by St. James, but which suggests that the Jerusalem preface was originally borrowed from the Egyptian tradition of Alexandria”, and later, “there is a relationship between St. James … and the equivalent parts of the Liturgy of St Basil, which is not close enough to describe as ‘borrowing’ on either side but which is nevertheless unmistakable in places. It might well be accounted for by their being independent versions of the same original tradition.”[19] Archdale King (1890-1972), another celebrated liturgist, also observes several similarities between Coptic St. Basil and St. James.[20]

In 1974 Geoffrey Cuming (1917-1988) suggested that the eucharistic prayer in St. Cyril’s Mystagogic Catecheses did not have the same structure as the West Syrian anaphoras, but was closer to Egyptian St. Mark. He argued that Cyril followed the Egyptian anaphoras (especially the Strasbourg Papyrus) in having an epiklesis before the institution narrative and that Cyril moved them from their position in Mark before the Sanctus to the end of the Eucharistic prayer. Professor Walter Ray, however, suggests a different hypothesis, “To think of these as Egyptian elements in the Jerusalem liturgy, however, as Cuming also did, may get the direction of influence wrong. If Jerusalem is the common source for the anaphoral tradition of Alexandria and Rome, then we must be approaching a very early form of Christianity. I am not proposing that Jerusalem is the source of this tradition, but I offer it as a possibility worthy of further consideration.”[21]

John Fenwick’s 1992 investigation into the common origin of the anaphoras of St. Basil and St. James attempted to explain this problem by postulating a common origin to both rites. Like Dix and King he observes that the anaphoras of St. Basil and St. James “exhibit sufficient common structure and wording to make a degree of dependence highly likely” and goes on to expound the theory that “the similarities are not due in any substantial way to the influence one on the other … But rather that the fact that each represents an independent reworking of a common original, an original which is preserved most faithfully in the Egyptian Version of the Liturgy of St. Basil.”[22]

Fenwick suggests that a fragment of a Sahidic version of the anaphora of Coptic St Basil (which he calls ES-Basil) published in 1960 by Jean Doresse and Emanuel Lanne of Louvain University is a very primitive variant of an even earlier text (which he calls Ur-Basil) which was the root onto which the remnant of the Liturgy of Saint James was grafted. He supports his hypothesis with detailed textual analysis, which makes fascinating reading and is a valuable contribution to liturgical research.

In 1989 Bryan Spinks, Professor of Liturgical Study at Yale Divinity School, believing that the evidence of Egyptian influence was inconclusive, argued against Cuming’s hypothesis and contended for the traditional West Syrian origins and structure of the Cyriline anaphora. He attributed the similarities between Cyril and the Egyptian anaphoras arose because of their common use of the Septuagint.

Burreson believes that the development of the anaphora in such a cosmopolitan city as Jerusalem “cannot be linked solely to the influence of one see, nor identified with one specific type of anaphora (i.e. West Syrian [Antiochene] or Alexandrian). It most certainly attests to a variety of influences from numerous areas, as well as its own peculiarities, and can only represent how those influences were assimilated within Jerusalem’s unique environment.”[23]

Wide influence of the Hagiopolite liturgy

The worship of the church in Jerusalem was to have a wide influence on the early Christian world and many liturgical practices used in the holy week services of both East and West have a common origin. Father Josef Jungmann (1889-1975) traces numerous instances of the Roman Rite being influenced by the Liturgy of St. James.[24] Bishop Frere[25] mentions the noticeable influence of St. Cyril’s lectures in the awakened interest in the work of the Holy Spirit shown in Persia, mentioning Aphraat (337-45) and St. Ephraim (c. 308-73), as well as the Egyptian Rite.[26]

Even the Imperial capital was deeply influenced by the Hagiopolite liturgy. Stig Simeon R. Frøyshov of the University of Oslo, states, “The rite of Jerusalem lies at the roots of the Byzantine rite, together with that of Constantinople, as one of the two constituents of the Early Byzantine liturgical synthesis that is usually called the Byzantine rite.”[27] He notes that three of the six elements of the Byzantine rite came from Jerusalem: the Psalter, the Horologion and the hymnic genres, as well as the oldest layer of hymnody. “Byzantine liturgy can be properly understood only in the light of both branches of its roots.”[28]

Comper calls the Jerusalem Liturgy “probably the most ancient Liturgy in actual use, and one which, more or less, governed the form and structures of other Liturgies.”[29] Bouyer, however, asserts that its “unfailing logical unity, the continuity of its development, and the impeccable Trinitarian schema … are all irrefutable signs not only of a late dating, but of a well thought-out structure, that remodelled the traditional materials with hardly believable daring.”[30] He notes that Bishop Frere maintained that this was “the ideal liturgy, conceived and developed on a plan which is substantially primitive, even if its working form represents an undeniably advanced evolution. The continuity of its development and the logical unity of the Trinitarian structure in which it is inscribed seem to him to be guarantees of the quasi-apostolic antiquity of this Eucharistic schema.”[31]

Surviving translations of St. James into Armenian, Ethiopian and Georgian show the extent to which its use had spread. It also spread to Thessaloniki and the extremities of the Byzantine Empire in Western Europe. Michael McCormick has shown that as late as 800 at least one of the Greek monasteries in Rome used the Liturgy of St. James rather than the Byzantine Rite, and that there were clear differences between the liturgical practices of Sicily and Calabria on the one hand and Apulia on the other. The former derived significant elements from Syria and Palestine rather than Constantinople.[32]

Primitive manner of reception retained

The rubrics of the Greek Liturgy of St. James provide for the distribution of the Holy Body into the hands of the faithful. This is consistent with St. Cyril’s instruction to the catechumens on the mode of receiving Holy Communion and reflects the primitive usage of the early church although it differs from the later use of the Byzantine Churches who administer both the Body and the Blood by the spoon and the Copts, who place the Body directly into the communicant’s mouth.

Many authorities believe that when St. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-c.215) wrote[33] “in the distribution of the Eucharist according to custom, some permit each one of the people individually to take his portion”, he is referring to receiving communion into the hand. St. Cyprian (c. 200-258), Bishop of Carthage, paraphrases St. Paul’s imagery in Ephesians VI when he speaks of arming the right hand with the sword of the spirit, “that it may bravely reject the deadly sacrifices; that, mindful of the Eucharist, the hand which has received the Lord’s body may embrace the Lord Himself, hereafter to receive from the Lord the reward of heavenly crowns.”[34]

However, ensuring that the consecrated gifts were handled reverently was of great importance to early Christian writers. Origen (c. 184-254) insists the faithful must be careful that no portion of the consecrated elements should fall to the ground[35], whilst Tertullian (c. 160-225) was horrified that those who were engaged in the making of idols, if admitted to church membership, “should apply to the Lord’s body those hands which confer bodies on demons”, or if they should become clerics, “deliver to others what they have contaminated.”[36] He also mentioned how Christians felt “anxious dread lest any portion of the bread or wine should fall to the ground.”[37] It was in this spirit of reverence for the sacrament that St. Cyril of Jerusalem wrote:

“In approaching therefore, come not with thy wrists extended, or thy fingers spread; but make thy left hand a throne for the right, as for that which is to receive a King. And having hollowed thy palm, receive the Body of Christ, saying over it, Amen. So then after having carefully hallowed thine eyes by the touch of the Holy Body, partake of it; giving heed lest thou lose any portion thereof; whatever thou losest, is evidently a loss to thee as it were from one of thy members. For tell me, if anyone gave thee grains of gold wouldest thou not hold them with all carefulness, and thy guard against losing any of them, and suffering loss? Wilt thou not then much more carefully keep watch, but not a crumb fall from thee what is more precious than gold and precious stones? Then after thou hast partaken of the Body of Christ, draw near also to the Cup of His Blood; not stretching forth thine hands, but bending, and saying with an air of worship and reverence, Amen, hallow thyself by partaking also of the Blood of Christ. And whilst the moisture is still upon thy lips, touch it with thine hands, and hallow thine eyes and brow and the other organs of sense. Then wait for the prayer, and give thanks unto God, who has accounted thee worthy of so great mysteries.”[38]

An interesting account in the Encomium of Pope Alexander of Alexandria provides evidence of this practice originally prevailing among the Copts. It recounts how there was a man in Alexandria whose hands were crippled (twisted so that he could not straighten them at all). As there was a service, he went to the church and desired to receive the Holy Mysteries from the hands of Pope Theonus (282-300) but because his hands were crippled, he opened his mouth to receive them. The Pope said to him, “My son, stretch forth your hands and take yourself.” Immediately his hands became straight and he stretched them forth and received the Holy Mysteries and glorified God.[39]

Other texts show that this mode of reception was universally employed until the fifth century. St. Basil the Great (329-379), writing to the Patrician Cæsaria concerning the regularity of communion says,

“At Alexandria and in Egypt, each one of the laity, for the most part, keeps the communion at his own house, and participates in it when he likes. For when once the priest has completed the offering, and given it, the recipient, participating in it each time as entire, is bound to believe that he properly takes and receives it from the giver. And even in the church, when the priest gives the portion, the recipient takes it with complete power over it, and so lifts it to his lips with his own hand. It has the same validity whether one portion or several portions are received from the priest at the same time.”[40]

When St. Ambrose (c. 340-397), Bishop of Milan, confronted the Emperor Theodosius following the massacre of Thessalonica, he asked, “How could you with such hands presume to receive the most sacred body of our Lord?”[41] We are told how his close contemporary, St. John Chrysostom (c. 347-407), performed a miracle involving a faithless woman who, having received the sacrament into her hands, slyly passed it on to her maid-servant.[42] St. Augustine (354-430), Bishop of Hippo, wrote to Petilian, the Donatist Bishop of Cirta, of another bishop “in whose hands you placed the Eucharist, to whom in turn you extended your hands to receive it from his ministering.”[43] As late as 692 the Quinsext Synod in Trullo, addressing the issue of those who out of false piety brought vessels made of precious metals to receive the sacrament, responded with canon CI, “Whoever comes to receive the Eucharist holds his hands in the form of a cross, and takes it with his mouth; whoever shall prepare a receptacle of gold or of any other material instead of his hand, shall be cut off.” The polymath Syrian monk, John of Damascus (675-749), witnesses to the continuity of this tradition: “Let us draw near to it with an ardent desire, and with our hands held in the form of the cross let us receive the body of the Crucified One: and let us apply our eyes and lips and brows and partake of the divine coal, in order that the fire of the longing, that is in us, with the additional heat derived from the coal may utterly consume our sins and illumine our hearts, and that we may be inflamed and deified by the participation in the divine fire.”[44]

A Common Rite divided

The evolution of the Liturgy of St. James continued until approximately the late fifth/early sixth century, when the Christological disputes arising at the Council of Chalcedon (451) resulted in lasting divisions in the Christian East. The eminent philologist, Father Louis Duchesne (1843-1922), notes, “The fact that the Jacobites have preserved it in Syriac as their fundamental liturgy proves that it was already consecrated by long use at the time when these communities took their rise – that is to say, about the middle of the sixth century.”[45] At some point after this the rite divides into two distinctive liturgical traditions, Greek St. James and Syriac St. James, used respectively by the Chalcedonians and the non-Chalcedonians, each reflecting their own character but with remarkable convergence in the anaphora of each. Both were enriched with additional prayers and ceremonies, but the maxim of the Abbé Charles Mercier (1905-1978), who edited the Greek recension of James, still holds good, “Quand une liturgie est attribuée à une personnage, il s’agit l’anaphore.”[46]

Several attempts have been made to reconstruct the sixth century text to establish the form and structure before the separation, but this will always prove elusive. John Fenwick’s warning that “the fact that two independent versions of an anaphora have material in common does not mean that the material concerned is ancient – it may be a late addition in one version which has been borrowed by the other” and “material found only in one version may be genuinely ancient but have been lost or replaced in other versions.”[47] One such attempt, by K. N. Daniel, a Malalayee lay church historian, liturgist, and reformed theologian, [48] resulted in a simplified Trisagion, the Creed, the Kiss of Peace, three pre-Anaphoral prayers (“O God and Master of all …”; “O only Lord and merciful God …”; “O God, Who through Thy great and ineffable love for mankind …”) and the Anaphora comprising the Sursum Corda, Preface, Sanctus & Benedictus, the Institution Narrative, the Anamnesis, Epiklesis, Lord’s Prayer and a Prayer invocating Grace (“We Thy servants, O Lord, have bowed our necks to Thee …) and the blessing “Holy things for holy persons.”

The Trisagion is a song of entry, which was originally sung during the initial procession into church. There are many traditions about its origin. One is that following an earthquake in Constantinople in the reign of Theodosius II (408-450), as he and Patriarch Proclus (434-446) were leading a procession invoking God’s mercy, a child was briefly caught up to heaven, where he heard the angels chanting the Trisagion. The liturgist, Dr. Stéphane Verhelst, believes it was used in the fifth century in processions on rogation days, along with litanies (ectenes).[49] By the sixth century it was in use in Syria, Constantinople, and Jerusalem. Its common use in both the Greek and Syriac texts suggests that it had been introduced prior to Chalcedon (451). However, the Syriac text has the additions of the words “who was crucified for us” which were introduced by Peter ‘the Fuller’, non-Chalcedonian Patriarch of Antioch (471-488). The British Orthodox Church follows the Coptic version of the Trisagion, based on the tradition recorded by Ibn Siba‘ in the thirteenth century, in his Kitab al Jawharah, that Saints Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, while giving burial to the body of Christ, heard the angels saying, “Holy God, Holy Mighty One, Holy Immortal One,” and at the words “Holy Immortal One,” Christ opened His eyes in their face. Then Joseph and Nicodemus said, “Who wast crucified for us, have mercy upon us.”[50] Ibn Siba‘ also said that the Trisagion is repeated thrice to accord with the number of the Holy Trinity and that the word “Holy” in the Trisagion (verses 1-3) is repeated nine times in reference to the nine angelic orders, whose worship in heaven is the prototype of the worship of the church.

Verhelst develops the ideas of Canon John Wilkinson, Director of the British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem (1979-1984), about the Jewish origins of the liturgy of St. James[51], highlighting five elements: the Prayer of the Trisagion, the Offertory Prayer, the Penitential Confession, the Ectenes and the Great Synapte as possessing Jewish parallels. He believes that the Prayer of the Trisagion in Greek St. James was not originally a Trisagion prayer but a prayer of parastasis, or vigil, where the reference to the Trisagion was later added. A different prayer is to be found in the oldest Georgian text, with some grammatical inconsistencies possibly deriving from semitic sources leading some scholars to posit a literary relationship between the two with a Palestinian origin. Verhelst suggests that this might be the work of a Greek priest whose language was Aramaic[52] but argues a developed case for St. James retaining distinctive Judea-Christian roots[53]

The Rev’d Dr. Baby Varghese, a Professor at the Orthodox Theological Seminary at Kottayam, suggests that the Greek text of the Anaphora was translated into Syriac before the end of the sixth century and quotes from the research of Gabriel Khouri-Sarkis (1898-1968)[54] to demonstrate that the Syriac version retains several examples of literal renderings into Syriac of Greek words and phrases. However, he admits that its origins and diffusion are obscure and that scholars differ as much as two hundred years in their opinion about when it was done. Varghese suggests that the impetus was the resettlement of non-Chalcedonians in the Syrian-speaking regions of Mesopotamia on the Roman-Persian border.[55]

Dr. Matti Moosa, writing about the Syriac Liturgy notes, “For it is certain that many additions have been made to it through the course of time.” In the sixth century the first Syriac translation of the complete Greek text of the Anaphora of St. James was made by Mar Yaqob Burdana, also known as Jacob Baradaeus (505-578), but this was not considered sufficiently accurate and a further translation was made by St. Jacob of Edessa (640-708). Moosa also mentions the tradition that when St. Jacob of Edessa, who was a celebrated Greek scholar, undertook the revision of the Syriac text of the liturgy (known by scholars as ‘the New and correct Recension’ or NCR), he did so according to the Greek text. However, this tradition has now been challenged by two modern philological scholars, Rűcker[56] and Heiming.[57] Proud of its Antiochian heritage, the Syriac Church saw the Greek texts as authoritative. Baby Varghese remarks that the Greek antiphons of St. Severus of Antioch were translated into Syriac in the early sixth century by Paul of Edessa and later revised by Jacob of Edessa, while the manuscripts of the baptismal liturgy and other special services claimed to be translations of the Greek originals. Even the ‘Syro Hexapla’[58] was preferred over the Peshitta Old Testament in most of the Tur Abdin monasteries. Renaudot[59] asserts that if we compare Syriac St. James with Greek St. James not only do the contents of the prayers, but their very wording, as well as the arrangement of the ritual, prove that the latter is the original form from which the former is derived.

Later liturgists: Moses Bar Kepha, Bishop of Mosul (813-903) and Mar Dionysius Bar Salibi, Bishop of Amid, enlarged the text by the addition of further prayers, whilst in the Persian Maphrianate, Mar Gregorios Bar Hebraeus (died 1286) abridged the text of Jacob of Edessa, thus giving the churches of the Syriac tradition a longer and a shorter form of St. James. The oldest manuscript version of Syriac St. James probably dates from the 8th or 9th century and is in the British Library.[60]

The Syriac Liturgy of St. James subsequently introduced some seventy-nine anaphors, attributed to various apostles (St. Mark, St. Peter, St. John the Evangelist, Twelve Apostles); hierarchs such as St. Xystus (died 251) and St. Julius of Rome (died 365), St. John Chrysostom (died 440), St. Cyril of Alexandria (died 444) as well as specifically Syriac fathers: St. Jacob of Sarug, Bishop of Batnan (died 521), St. Philoxenus of Mabbug (died 523), Patriarch St. Severios of Antioch (died 538) and Mar Dionysius Jacob Bar Salibi, Bishop of Amid (died 1171). These continued right into the sixteenth century, the latest being made in 1575.[61] Though they invariably follow the structure of St. James, in the wording of the individual prayers they differ from one another.[62] Although this was an expression of the vibrant spirituality during the golden age of liturgical creativity not all anaphoras were of the same quality. Vargese admits that,

“After the thirteenth century, especially the ruthless massacres of Christians under Tamerlane, Syriac Christianity entered a phase of speedy decline. The prelates, clergy and the monks were somewhat illiterate and theological and liturgical creativity were at their lowest ebb. The clergy found it rather difficult to understand the meaning and the richness of the liturgical texts …. The newly composed liturgical texts, including the anaphoras, were often mediocre, in both their content and language.”[63]

New elements were introduced, such as elaborate preparation rites, dramatic blessing of the censer in the pre-anaphora, inaudible prayers and an elaborate fraction.[64] Varghese dates the elaboration of the fraction to the ninth-tenth century with the addition of a series of complex rites and prayers articulating the mystery of the passion, and notes that as late as the eleventh century some dioceses were still using a simple fraction. However, by the twelfth century this had been replaced with a longer formula, relating various gestures of the fraction to the passion, death and resurrection of Christ.[65]

Hellenisation or Byzantinisation ?

If the Syrian text of St. James underwent such changes, there are also elements in the Greek text which augment the rite used prior to Chalcedon. Scholars differ as to whether these are an on-going process of Hellenisation or later Byzantinisation. Kurian Valuparampil reminds us that the Greek Christians were an integral part of the original Church of Jerusalem (Acts VI: 1) and that parallel worship undoubtedly took place in Greek and Aramaic. He suggests that the original Antiochian liturgy was derived from Jerusalem in the first century and later reinforced by the presence of Christian refugees following the Fall of Jerusalem in 72 A.D. This view would account for the strong tradition of continuity from St. James, but does not explain the process by which this was transformed into a developed liturgical form common to both the Greek and Syriac texts. Vargese reminds us that,

“In spite of the cultural and linguistic differences, there is a considerable interdependence among the Eastern liturgies. The Syro-Antiochene tradition is largely indebted to the Hellenistic culture. Severus of Antioch, the great organizer of the Syrian Orthodox liturgy, was a man of Greek culture. In the ninth and tenth centuries, the West Syrians came under Byzantine influence, especially in the case of hymnody. Thus several ‘Greek canons’ found their place in the Syrian Orthodox liturgy.”[66]

In his examination of the liturgy of St. James, Sir William Palmer identified a number of “evident signs of alterations and adaptations to the Greek rite.” These include the Cherubikon; the procession of the elements during the saying of the prayer O Theos, O Theos emon (O God, my god) at the Great Entrance which is from the liturgy of St. John Chrysostom; the prayer kurie O Theos, O ktisas (Lord God, the Creator) from St. Basil’s liturgy; the anthem sung before or after the name of the holy virgin in the commemorations (Chaire, Kecharitomene – Hail, full of grace & Axios Estin – It is truly meet); the anthem O Monogenes before the Tersanctus; and a prayer from St. Basil’s Liturgy.

Salaville notes that the Greek Liturgy of St. James “goes back to sixth, perhaps to the fourth century, but later modifications have been introduced into the existing manuscripts.” He also remarks that the manuscripts which contain the liturgy are unfortunately late tenth century and the text shows many signs of infiltrations suggested by Byzantine usage.[67] Hammond instances the two liturgical hymns: O Monogenes and the Cherubikon as later interpolations. O Monogenes (“O Word Immortal”) was originally composed as an entrance chant (eisodikon), which the Byzantines attributed to the Emperor Justinian I (527-565), who they assert, wrote it in 528 when Severus, Patriarch of Antioch was his guest. The Syrians, however, ascribe it to Severus himself and date it from 512-518. It is strongly anti-Nestorian in character and also attacks the heresy of Eutyches.

The absence of a developed Prothesis or Rite of Preparation, such as we find in the Byzantine Rite, was often quoted as an indication of the primitive nature of the Liturgy of St. James. In more recent years, when celebrated in Byzantine churches it has been usual for the the Byzantine Prothesis to be used to remedy this absence. However, the discovery of rudimentary prothesis prayers in Georgian manuscripts of St. James found in 1975 on Mount Sinai have led some scholars to modify this view. Verhelst attributes this to a Syrian influence, because the Palestinian tradition already possessed a non-Eucharistic prayer of offering before the introduction of the rite. One of the prayers is entitled “Prayer when preparing to place the offering on the altar” and he suggests that although the Prothesis was normally performed on the altar, it could also be conducted in the diakonikon, or on a prothesis table. Archaeology witnesses to the Palestinian diakonikon, usually being a side room to the north, overlooking the nave, sometimes, but not always, containing an altar.[68] He attributes this rite to the first half of the sixth century, around the same time as the three prothesis prayers of the Georgian use were introduced. Verhelst also notes that the Melkite-Egyptian rite conserved in two manuscripts of the Liturgy of St. Mark confirms his hypothesis of a non-Chalcedonian origin of the Prothesis, originating in Egyptian St. Basil.[69]

The modern Syriac Liturgy of St. James has no Great Entrance, which we find in Greek St. James, but this should not lead us into thinking that the Great Entrance is itself a Byzantinisation. Consistent with the liturgical directions given in the VIIIth book of the Apostolic Constitutions, following the dismissal of the catechumens “When this is done, let the deacons bring the gifts to the bishop at the altar”, the Liturgy of St. James had a solemn Offertory procession. Theodore of Mopsuestia (c. 350-428), in describing the liturgy to the catechumens of his day, states:

“We must think, therefore, that the deacons who now carry the Eucharistic bread and bring it out for the sacrifice represent the image of the invisible hosts of ministry, with this difference, that, through their ministry and in these remembrances, they do not send Christ our Lord to His salvation-giving Passion. When they bring out (the Eucharistic bread) they place it on the holy altar, for the complete representation of the Passion, so that we may think of Him on the altar, as if He were placed in the sepulchre, after having received His Passion.”[70]

In a homily by James of Sarug, who died in 521, he draws parallels with the shewbread in the Old Testament and the Christian Offertory:

“And if the former carried it in procession upon their hands, how much more should the latter apply themselves to it. And if the Old conveyed it in procession … how much more should the New be eager for its honour … It was not Melchizedek that taught the Church what she should do: on her Lord she gazed, and as He did, so does she daily … Jesus, who was God, taught her the Mystery. And behold, she cares for it, and bears it in procession, and glories in it …”[71]

Moses Bar Kepha, Syriac Orthodox Bishop of Beth Remman (Barimma), Beth Kyanaya and Mosul, from about 863 until his death in 903, wrote an Exposition of the Jacobite Liturgy[72], in which he describes a ceremonial procession in which the bread and wine are brought out from the sanctuary, carried among the people and brought back to the altar,

“Concerning the going forth of the mysteries from the altar, and their going about the nave and their return to the altar: That the mysteries go forth from the altar, and go about the nave in seemly order, and return to the altar, makes known that God the Word came down and was made man, and went about in the world and fulfilled the dispensation for us, and then ascended the cross, and afterwards ascended to His Father.”

What is probable, therefore, is that the Offertory Procession fell out of use in Syriac St. James. Varghese suggests,

“The Syriac Orthodox Liturgy lacks the ‘pomp’ of the Byzantine celebrations. External conditions made such pompous celebrations rather difficult. Whether in the Byzantine Empire, or in the Sassanid Persia or in the Muslim states, the Syrian Orthodox Christians always lived under constraints. Throughout their history, they were a community struggling for survival. Therefore their churches were modest in size and architecture and were often too small for solemn processions, unlike the Byzantines. The processions that were once held with solemnity (for example the entrance procession) gradually disappeared or were limited to the space around the altar.”[73]

It is evident from Theodore’s account that the Entrance was made in silence, but the solemnity of the rite soon called for embellishment. It is the introduction of the Cherubikon and the involvement of all the sacred ministers in the procession, which represents the Byzantinisation and turns the Entrance into a great one. It has also become more than an offertory chant because the words and imagery relate to the entire Eucharistic liturgy. It is much more than “merely a ceremonialised form of [the] purely utilitarian bringing of the bread and wine to the table”[74] Taft asserts that, “The tendency to consider the Oriental pre-anaphoral rites, including the procession with the gifts and its accompanying chants, in terms of ‘offertory’, ‘offertory procession’. ‘offertory chant’ is a prejudice based on later, largely Western, liturgical categories.”[75] However, the imagery in some translations of Christ “borne aloft on shields and lances” clearly refers to the acclamation of a Byzantine Emperor.

In the Byzantine rite the Cherubikon has three variants used for Holy Thursday, Holy Saturday and for the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. The one used in the British Orthodox Church is the Holy Saturday variant (based on Zecharia II: 13). It first appears in a manuscript, a Prophetologion (Old Testament lectionary used at Vespers) Sinai Gr. 14 from the 11-12th century and later in a typicon Sinai Gr. 1098 (guide to the variable hymns of the liturgy) dated 1392, both from Palestine. Taft suggests it originates from Jerusalem,[76] and highlights its closeness to St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s commentary,

“After this the Priest cries aloud, ‘Lift up Your Hearts’. For truly ought we in that most awful hour to have our heart on high with God, and not below, thinking of earth and earthly things. The Priest then in effect bids all in that hour abandon all worldly thoughts, or household cares, and to have their heart in heaven with the merciful God. Then ye answer, ‘We Lift Them up unto the Lord’: assenting to him, by your avowal. But let no one come here, with his lips can say ‘We lift up our hearts to be Lord’, but in mind employs his thoughts on worldly business. God indeed should be in our memory at all times, but if this is impossible by reason of human infirmity, at least in that hour this should be our earnest endeavour.”[77]

Later, around the ninth century, the Jerusalem Liturgy became subject to ‘Byzantinisation’. Dr. Daniel Galadza, in his study of this process, attributes it to the period of strained relations between Muslim rulers and their Christian subjects, when many of Jerusalem’s holy sites fell into disrepair. During this time elements from the liturgies of St. John Chrysostom and St. Basil were introduced. He believes the process was virtually complete by the 13th century, although the Byzantinisation of the liturgy did not necessarily imply the adoption of Byzantine culture in Jerusalem. Greek language and culture certainly persisted, even flourished, in Palestine during some periods of Arab occupation.[78]

In the twelfth century Mark III, Greek Patriarch of Alexandria (1180-1209) submitted a question to the learned Byzantine canonist, Theodore Balsamon (later Theodore IV, Patriarch of Antioch 1185-1199), as to whether the liturgies used in Alexandria and Jerusalem, purporting to have been written by the Apostles Mark and James should be received by the church or not. Theodore, who resided all his life in Constantinople, even after his election to the See of Antioch, replied:

“We see, therefore, that neither from the Holy Scriptures nor from any canon synodically issued have we ever heard that a Liturgy was handed down by the holy Apostle Mark: and the thirty-second canon of the Council held ‘in Trullo’ is the only authority that a mystic Liturgy was composed by the holy James, the brother of the Lord. Neither does the eighty-fifth canon of the Apostles nor the fifty-ninth canon of the Council of Laodicea make any mention of these Liturgies, nor does the Catholic Church of the Œcumenical See of Constantinople in any way acknowledge them. We decide therefore that they ought not to be received; and that all Churches should follow the example of New Rome, that is Constantinople, and celebrate according to the tradition of the great teachers and luminaries of the Church, the holy John Chrysostom and the holy Basil.”[79]

Improving Scholarship

We owe the first printed texts of the Liturgy of St. James to French classical scholars and printers to the Kings of France. In 1560 Guilaume Morel (1505-1564) printed in Paris a Greek text of St. James of unknown provenance which became the textus receptus. Interest in ancient liturgies encouraged a number of eminent Catholic scholars to seek for old manuscripts. The Dominican Bishop, Jacques Goar (1601-1653) made a great study of Eastern liturgies whilst residing in Chios as Missionary Apostolic. Not only did he personally observe many of these but he collected manuscripts, which led to their rediscovery in the West. Joseph Aloys Assemani (1710-1782), a Maronite orientalist, published thirteen volumes of such texts between 1749-1766, but sadly offers no information as to the source of his text of St. James, which appears to have been reproduced from Morel. The hunt for liturgical manuscripts during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries became quite a compulsion for Western scholars. We hear how the Benedictine palaeographer, Dom Bernard de Montfaucon (1655-1741) found that the monks at Rossano – the knowledge of Greek having been lost – neglected the precious contents of their library and books were lying untouched and neglected, and were in imminent danger of being destroyed. Only their timely removal to Rome prevented this. He also records how Pope Sixtus IV (1471-1481), when Archbishop of Rossano, “wearied and tired by the persistency with which strangers came to examine the charters and documents contained in the library, ordered all of them to be buried, and thus got rid of the nuisance.”[80]

British interest in the text began with Bishop Rattray (1744) William Trollope (1848) and John Mason Neale (1849, 1859 & 1868), who all drew heavily on the textus receptus. In 1845 the Reverend Sir William Palmer (1803-1885) published his Origines Liturgicæ, which contained a learned chapter on the Liturgy of the Patriarchate of Antioch. In 1884 Professor Charles Anthony Swainson’s The Greek Liturgies from original authorities was compiled using four manuscripts[81], which he collated with the textus receptus, although this work was criticised for the inexactness of collation.

The Rev’d Frank Ernest Brightman (1856-1932), an Anglican priest, was a distinguished liturgist and sometime Librarian of Pusey House Oxford and a Fellow of Magdalen College. In Volume I (Eastern Liturgies) of Liturgies Eastern and Western (1896), he utilised other manuscripts, mostly dating from the 16th and 17th centuries or later, although he found a 14th manuscript from Sinai. With this wider range of texts available Brightman argued that they fell into three distinct geographical groupings: eastern (Patriarchate of Jerusalem), western (Zante) and intermediate (Thessalonica).

The discovery in 1908 of an Old Armenian Lectionary, probably dating from between 417 and 439 and translated from a Greek original, which ties in with Egeria’s accounts of lessons she heard read at Jerusalem, provides another missing link enabling us to partially reconstruct the liturgical worship of Jerusalem at this period.[82]

The German philologist, orientalist and liturgist Dr. Anton Baumstark the younger (1872-1948), who founded Oriens Christianus, and the German Catholic theologian, Theodor Schermann (1878-1922), were the first to bring to light the manuscript, Vaticanus graecus 2282 when they published a short account of it in 1903 “Der älteste Text der griechischen Jakobosliturgie” in Oriens Christianus. They traced the origins of this text to Damascus, a Metropolitanate of the Patriarchate of Antioch, and suggested a date towards the end of the seventh and beginning of the eight century. It was published for the first time by A.-J. Cozza-Luzi in 1903. Dom B. -Ch Mercier, after a scientific re-evaluation, redated it to the ninth century. It was this text which used the expression in the consecration of the cup “and filled it with the Holy Spirit”. Mercier’s text is “critical”, which means it does not follow a single manuscript but seeks to establish a text which is both correct and relatively old, which in most instances is the manuscript Vaticanus 2282; which is considered as “certainly the most faithful of the Greek review witnesses.”[83]

As recently as 1975 many new manuscript finds on Mount Sinai have uncovered previously lost texts of the St. James Liturgy. Five new Greek manuscripts of St. James were revealed in the New Sinai finds, but these dated from the tenth and eleventh centuries or later. The new Sinaitic manuscript also includes a large batch of Georgian manuscripts of St. James: 141 manuscripts are currently numbered, ten rolls, plus hundreds of scattered fragments which are not yet identified.[84] Two of these[85] are particularly interesting because they are complete and seem to bear no trace of later revision in the Greek tradition. Although the Tbilisi manuscript is early eleventh century and the Graz/Prague one can be precisely dated to 985, Verhelst believes they represent a sixth century use, when there was a prosthesis rite at the beginning of the liturgy. There also appear to be a shorter and a longer version of the Liturgy of St. James. As six manuscripts dating from the tenth century contain the shorter version, scholars believe this indicates that both were used until the beginning of the eleventh century. The inclusion of the entire shorter text in the longer version also leads to the assumption that the shorter text is closer to the original form, dating from as early as the sixth or seventh centuries, with the longer text resulting from later developments and supplementation.[86]

Liturgical Revival of St. James

By the 19th Century, the liturgy of St. James was rarely used in the Byzantine Churches, it being celebrated some three times a year in Jerusalem and on the Greek island of Zante (Zakynthos): on the feast day of St. James the Apostle (23 October/5 November), on the Sunday after Christmas and the Feast of the Seventy Apostles on 4/17 January. It owes its modern revival to Bishop Dionysius Latas (died 1894) of Zante, who had been educated at Jerusalem, who published an edition of the Liturgy. On 1 September 1886 he celebrated it in the Church of St. Irene in Athens in the presence of Queen Olga, to mark the coming-of-age of Crown Prince Constantine of Greece. This edition attempted to eliminate Byzantine accretions and to reorganise the rubrics. In 1900, Patriarch Damianos of Jerusalem (1897-1931), revived it for one day in the year, moving it from 23 October to 31 December. It was first celebrated again in 1900 (on 30 December as an exception) in the church of the Theological College of the Holy Cross with Archbishop Epiphanios of Jordan, as the principal celebrant, assisted by a number of concelebrating priests. The Latas edition was used, but it was reported that Archimandrite Chrysostomos Papadopoulos had been commissioned to prepare another and more correct edition[87]

Generally, however, it is only celebrated in Jerusalem on the Feast of St. James (23rd October) and on the first Sunday after Christmas. Today, among the Byzantine Orthodox it remains a permitted alternative to St. John Chrysostom and has increased in popularity, although it is still only rarely celebrated. In the Syriac Churches, however, St. James is flourishing and is the regular rite used by the Malankara Orthodox communities of South India, who received it from their Mother Church, the Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch.

The liturgy of St. James was unknown in the Russian Orthodox Church as it had already been replaced by the Byzantine Rite when Russia was evangelised. A Church Slavonic translation of the Greek text was published by the learned Russian musicologist, Dr. Johann von Gardner (1898-1984) – then Hegumen Philip and later Bishop Philip of Potsdam – who held the Chair of Russian Liturgical Music at the University of Munich. This was authorised for liturgical use by Metropolitan Anastassij, head of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, after which its use became more widespread.

St. James and British Orthodoxy

The Liturgy of St. James was first used in the British Isles in the eighteenth century. It was adopted by the ‘Nonjurors’, the continuing hierarchy descended from the nine Anglican bishops and about 400 clergy who had been ejected from their sees and livings because they refused to swear allegiance to William and Mary, who had usurped the throne from King James II at the ‘Glorious Revolution’ 1688. Between 1716-1723 they corresponded with the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople and with the Russian Orthodox Church, about a possible reunion.[88] Although nothing came of these conversations at the time, it left the Nonjurors with a strong sympathy for the Orthodox East rather than Rome. Accepting the prevailing contemporary theory that the British Churches “first received their Christianity from such as came forth from the Church of Jerusalem, before ever they were made subject to the Bishop of Rome and that Church”, in the proposals they submitted to the Greek Patriarchs, the Nonjurors suggested, “That the Church of Jerusalem be acknowledg’d as the true mother Church and principle of ecclesiastical Unity, whence all other Churches have been deriv’d, and to which, therefore they owe a peculiar regard” and “That a principality of Order be in consequence hereof allow’d to the Bishop of Jerusalem above all other Christian Bishops.” In 1718 the more Catholic-minded bishops produced a new liturgy, drawing on the ‘Clementine Liturgy’ from the VIIIth Book of the Apostolic Constitutions to replace the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. Inevitably this led to further revisions and aware that, just as liturgical development had caused the Clementine Liturgy to become the Liturgy of St. James, so their own spiritual journey was leading them in the same direction. In 1734 the hapless Bishop Thomas Deacon (1697-1753) published A Compleat Collection of Devotions both public and private, taken from the Apostolic Constitutions, the ancient liturgies, and the Common Prayer Book of the Church of England with an alternative title page was also produced, The Order of the Divine Offices of the Orthodox British Church.[89]

Ten years later, in 1744 there was published posthumously The Ancient Liturgy of the Church of Jerusalem, being the Liturgy of Saint James, Freed from all latter Additions and Interpolations of Whatever kind, and so restored to it’s original purity: By comparing it with the Account given of that Liturgy by St. Cyril in his fifth Mystagogical Catechism. Its author was Thomas Rattray (1684-1743), a Scottish Nonjuror, Bishop of Brechin and subsequently Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church from 1739-1743. It is clear that J.M. Neale was not vastly impressed with Rattray’s scholarship, relegating his comments to rather dismissive footnotes, “Bishop Rattray, without assigning a reason, omits … the superfluous words.”[90] Again, in discussing some versicles not found in St. James, he archly observes, “It is rather strange that Rattray who is always suspecting interpolations, should in this instance suspect an omission.”[91] Later, when discussing a text he feels to have been interpolated, “And I wonder that Bishop Rattray does not class it as such; for the quotation he produces from S. Cyril … is surely not much to the point.”

Putting Rattray’s work into the context of his times, a more sympathetic critic has written,

“Rattray as a liturgist is of course a man of his time. Like many of his contemporaries, he tends to overestimate the nearness to the age of the Apostles of the text of the liturgy of St. James which he is establishing; he also tends seriously to underestimate the variety of liturgical forms which existed in the early Christian centuries. In that way he tends to attribute to the rite a greater authority than it can bear. Granted these limitations, however, his book remains a daring and imaginative piece of work, particularly in his proposal that this particular rite should be adapted for the use of congregations in his own day.”[92]

Of this liturgy, it was said, “It was too far removed in character from the service with which both priest and people were familiar to allow it any chance of being adopted in its own form by the church.”[93] Yet Bishop Rattray’s text served as the basis of a Communion Office, which was used in the Scottish Episcopal Church from 1764-1911 and again when revised in 1912, which in turn influenced the liturgy of the Episcopal Church in the United States. When Rattray’s Liturgy was publicly celebrated in Edinburgh Cathedral on Whitsunday (22 May 1994), one of those present observed,

“The celebration of a liturgy of an eastern pattern could also, I believe, corporately deepen and strengthen our hold on the mystery of Christ in its richness and multiplicity. Perhaps the strangest thing about this proposal is that it does not in the end entail us going outside our own tradition; rather it involves us in reclaiming something which is already in principle our own. If we are uniting ourselves with the fourth century in Palestine, we are doing so by way of the eighteenth century in Edinburgh. We go down the Royal Mile and find ourselves in Jerusalem.”[94]

Although the original mission of the British Orthodox Church in the nineteenth century derives from the Syrian Orthodox Church, the early bishops appear to have preferred to use variants of Western rites, presumably because they felt this was more appropriate to its mission to Europeans. It was not used until one of my predecessors, Archbishop John Churchill Sibley (1849-1938) published The Ancient Syrian Rite of the Holy Eucharist for Western Use in 1927, although his recension relied heavily on Brightman’s translation of Syriac St. James. This text was always used at our Bournemouth Church.

I had spent the early part of my liturgical life with the Glastonbury Rite, the work of my immediate predecessor, Mar Georgius (1905-1979) who felt that an indigenous British Orthodoxy would be best served by a neo-Gallican rite, along much the same thinking as his contemporary, Bishop Jean-Nectaire Kovalevsky de Saint Denis (1905-1970), Primate of l’Eglise Orthodoxe de France. Although Western in structure it had been heavily Byzantinised in its ceremonial and vestments. I had grown to love it and recognise its strengths, but I was not blind to its weaknesses either. Although all liturgy has an element of hybridisation, this took place in ancient times and over the intervening centuries the rites acquired a homogeneity distinctive to the spiritual tradition of each church. With the Glastonbury rite there was such a hotchpotch of traditions that the services had become overly elaborate and suffered from a certain degree of repetition. A distinctive liturgy necessitated its own horologion, ordinal, sanctorale, lectionary, rituale and propers, some of which were already in place but much of which had still to be written. Although liturgy is an essential part of the church’s life and tradition, I was concerned that too great a preoccupation with liturgy might be at the expense of mission. As a small, independent, missionary church we were also open to criticism for devising our own rites rather than identifying ourselves with the wider Orthodox family by using an ancient and universally recognised liturgy.

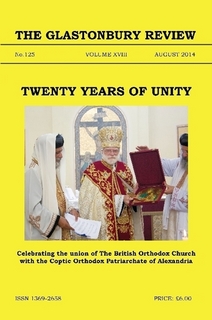

The decision in principle to adopt the Liturgy of St. James in place of the Glastonbury Rite had been taken prior to the beginning of our talks with the Coptic Orthodox Church but these now necessitated bringing the proposed schedule forward so that all the necessary changes coincided with our reception into the Patriarchate of Alexandria.

We had chosen St. James after much careful consideration because of its primitive and apostolic character. To think of it as an ‘Eastern’ as opposed to a ‘Western’ liturgy seems to me to be putting the emphasis in quite the wrong place. Perhaps because our congregations had been using a Byzantinised Western rite I felt it would not present too great a change of ethos. St. James, like St. Basil, was common to both families of Orthodox though there is far more common text in St. James. The many similarities with St. Basil are also very appropriate in view of our union with the Coptic Patriarchate, where St. Basil’s Liturgy is the most widely used. We chose Greek St. James because in spite of having been Byzantinised it is still closer to the primitive rite than Syriac Saint James, which has been more heavily embellished.

Where appropriate we have used good British hymnody. The translation of O Monogenes was made by Thomas Alexander Lacey (1853-1931), better known for his hymn based on the Advent Antiphons, ‘O Come, O come Emmanuel’. ‘Let all mortal flesh keep silence’ is a translation from the Greek by Gerard Moultrie (1829-1885). The Recessional of Saint James, based on the Greek text ‘is probably in a translation by Mar Georgius, though the English Hymnal contains another version by Charles Humphreys (1840-1921).

In considering appropriate ceremonial for the Liturgy of Saint James as celebrated in the British Orthodox Church it was felt that as far as possible it should follow the traditions of our Mother Church, especially as in all other services we were committed to follow the rites and ceremonies of the Coptic Church. Structurally this involved us in few changes as our own churches already had cubic free-standing altars and an ikonostasis. As we have seen, liturgy is constantly evolving and whilst both Greek and Syrian St. James are authentic heirs of the Hagiopolite rite, each has adapted itself to local traditions as well as undergoing the enrichment of cross-pollination from other authentic traditions. In discussing this with the late Pope Shenouda III he recognised the distinctive cultural differences required for effective mission among western Christians, whilst welcoming our desire to conform to the spirit of Coptic worship. This was signified when he established a permanent liturgical commission under my chairmanship authorising the British Orthodox Church “to consider appropriate translations of the Coptic Orthodox service books and the use of alternative forms of services drawn from ancient Western Orthodox sources which may be adapted to the local situation”, subject to his approval. In adopting the ceremony of the “Choosing and Procession of the Lamb” from the Coptic Liturgy of St. Basil, rather than the Byzantine prothesis, and the manual parts of the Coptic Fraction, we felt it provided that link with our Alexandrian heritage without disturbing the integrity of the Liturgy of St. James. Linked to this we adopted the Coptic cursi, known as the ark or throne. This is a consecrated box with hinged lids, which is permanently on the altar and is decorated with ikons, in which the chalice sits throughout the liturgy.

Of the several English translations available we chose to largely follow that of Dom Gregory Dix, who was not only a fine scholar but clearly had a feel for liturgical language. Until the Reformation all church services would have been in Latin, so the translation of the Holy Bible and the publication of an English Prayer Book were events of immense significance in British history. Shakespeare and Thomas Cranmer’s part in this great flowering of the English language have rightly been referred to as “not of an age but for all time” and provided a memorable foundation for public worship for many generations of Christians. We have also followed Dix in retaining that classical liturgical language shaped by the Authorised Version (1611) of the Bible and successive editions of the Book of Common Prayer. We believe that the language of the sacred, so much of which is poetic and figurative, needs to reflect a sense of the numinous. The Prince of Wales has reminded us that “Poetry is for everyone, even if it’s only a few phrases. But banality is for nobody. ….. We seem to have forgotten that for solemn occasions we need exceptional and solemn language – something that transcends our everyday speech. We commend ‘the beauty of holiness’; yet we forget the holiness of beauty. If we encourage the use of mean, trite, ordinary language, we encourage a mean, trite, ordinary view of the world.”[95]

His Holiness Pope Shenouda III approved these changes and in 1994 a provisional text was made available to the churches, which were invited to send in their observations about its practical implementation as well as the language. The response throughout the churches was amazingly positive and before long we began to feel as if we had never used any other liturgy.

One regular communicant has written, “After nearly twenty years of worshipping with the Liturgy of St. James the words of this beautiful edition have formed and guided my own personal prayers. The references and allusions to scriptural passages, which are many and apposite, provide a continuous source of spiritual sustenance, week in and week out, couched in poetic language which is expressed with that essential quality of conveying a sense of the numinous. I particularly value the Deacon’s Litanies for their comprehensiveness, without being either long-winded or trite; whilst the Cherubikon, sung at the Great Entrance, captures the realisation of our worship being united with the whole company of heaven before Christ our Lord, Who manifests Himself sacramentally as the Heavenly Bread, for the remission of our sins and eternal life. It is, I believe, ideally suited to public worship in English as it is both sublime and intelligible.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

John Paul ABDELSAYED, “Liturgical Exodus in Reverse: A Reevaluation of the Egyptian Elements in the Jerusalem Liturgy, pp. 139-161, in Issues in Eucharistic Praying in East and West: Essays in Liturgical and Theological Analysis, edited by Maxwell E. Johnson (Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota: 2010).

Zaza ALEKSIDZE et al, Catalogue of Georgian Manuscripts discovered in1975 at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, English translation by Mzekala Shanidze (Athens: 2005).

ANAPHORA. The Divine Liturgy of Saint James the First Bishop of Jerusalem according to the Rite of the Syrian Orthodox Church of Antioch, translated from original Syriac, includes The History of Saint James Liturgy by Dr. M. Moosa, (Metropolitan Mar Athanasius Yeshue Samuel, Archbishop of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the United States and Canada: 1967).

John F. BALDOVIN, Liturgy in Ancient Jerusalem, Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 9 (Grove Books, Bramcote, Nottingham: 1989).

-

BAUMSTARK & Theodor SCHERMANN, Der älterste Text der griechischen Jakobsliturgie, Oriens Christianus (Leipzig) III (1903), pp. 214-219.

Paul F. BRADSHAW, “The Influence of Jerusalem on Christian Liturgy” in Jerusalem: Its Sanctity & Centrality to Judaism, Christianity and Islam, edited by Lee I. Levine (Continuum, New York: 1999), pp. 251-259.

F.E. BRIGHTMAN, Liturgies Eastern and Western being the Texts original or translated of the Principal Liturgies of the Church, Vol. I. Eastern Liturgies (Clarendon Press, Oxford: 1896).

Louis BOUYER, Eucharist. Theology and Spirituality of the Eucharistic Prayer. Translated by Charles Underhill Quinn (University of Notre Dame Press, London: 1968).

Kent J. BURRESON, “The Anaphora of the Mystagogical Catechesis of Cyril of Jerusalem”, pp. 131-152 in Essays in Early Eastern Eucharistic Prayers, edited by Paul F. Bradshaw (Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota: 1997).

Dom R.H. CONNOLLY & H.W. CODRINGTON, Two Commentaries on the Jacobite Liturgy by George Bishop of the Arab Tribes and Moses Bar Kepha: together with the Syriac Anaphora of St. James and a Document entitled ‘The Book of Life’, Text and Translation Society, (Williams & Norgate, London: 1913).

Fred. C. CONYBEARE & Oliver WARDROP, “The Georgian Version of the Liturgy of St. James” in Revue de l’Orient Chrétien (Paris), Deuxième Série, Tome VIII (XVIII) – 1913, No. 1, pp. 396-410 and Tome IX (XIX) – 1914, No. 1, pp. 155-173.

R.H. CRESSWELL, The Liturgy of the Eighth Book of ‘The Apostolic Constitutions’ commonly called The Clementine Liturgy (SPCK, London: 1924).

-

L. CROSS, (editor), St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s Lectures on the Christian Sacraments: The Protocatechesis and the Five Mystagogical Catecheses (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, New York: 1995).

G.J. CUMING, “Egyptian Elements in the Jerusalem Liturgy”, Journal of Theological Studies 25, No. 1 (1974): 117-24.

-

J. CUTONE, “Cyril’s Mystagogical Catecheses and the Evolution of the Jerusalem Anaphora,” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 44 (1978): 53-64.

K.N. DANIEL, A Critical Study of Primitive Liturgies (CMS Press, Kottayam: 1937).

Juliette DAY, The Baptismal Liturgy of Jerusalem. Fourth and Fifth-Century Evidence for Palestine, Syria and Egypt (Ashgate, Aldershot: 2007).

DIVINE LITURGIE de la Sainte Oblation selon Saint Jacques, supplement L à la letter aux amis du sanctuaire copte-orthodoxe Saint Elie de Montpeyroux (2000).

Dom Gregory DIX, The Shape of the Liturgy (Dacre Press, Westminster: 1949).

James DONALDSON (editor), The Apostolical Constitutions, Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Vol. XVII (T & T. Clark, Edinburgh: 1880).

John Edward FIELD, The Apostolic Liturgy and The Epistle to the Hebrews, being a Commentary on the Epistle in its Relation to the Holy Eucharist, with Appendices on the Liturgy of the Primitive Church (Rivingtons, London: 1882)

John R.K. FENWICK, The Anaphoras of St Basil and St James. An Investigation into their Common Origin, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 240 (Ponificium Institutum Orientale, Rome: 1992).

Stig Simeon R. FRØYSHOV, “The Georgian Witness to the Jerusalem Liturgy: New Sources & Studies”, in Bert Groen, Steven Hawkes-Teeples & Stefanos Alexopoulos (eds), Inquiries into Eastern Christian Worship, Eastern Christian Studies 12 (Leuven: 2012).

Daniel GALADZA, Worship of the Holy City in Captivity. The Liturgical Byzantinization of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem after the Arab Conquest (8th-13th c.); Excerpta ex dissertation ad doctoratum (Pontificium Institutum Orientale, Rome: 2013).

Daniel GALADZA, “Liturgical Byzantinization in Jerusalem: Al-Biruni’s Melkite Calendar in Context”, Bollettino della Badia Greca di Grottaferrata III s. 7, 2010, pp. 69-85.

-

Jardine GRISBROOKE, Anglican Liturgies of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Alcuin Club Collections No. XL (SPCK, London: 1958).

-

Jardine GRISBROOKE, The Liturgical Portions of the Apostolic Constitutions: A Text for Students, Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 13-14, (Grove Books, Bramcote, Nottingham: 1990).

-

E. HAMMOND, Liturgies Eastern and Western being A Reprint of the texts, either original or translated, of the most representative liturgies of the Church from various sources (Clarendon Press, Oxford: 1878).

C.E. HAMMOND, The Ancient Liturgy of Antioch and other Liturgical Fragments being An Appendix to ‘Liturgies Eastern and Western’ (Clarendon Press, Oxford: 1879).

- HEIMING, Anaphora syriaca sanct Iacobi fratris Domini (ASy 2.2), Roma 1953.

Alcibiades K. KAZAMIAS, He Theia Leitourgia tou Hagiou Iacobou tou Adelfotheou ta nea sinaitika cheirographa [The Liturgy of Saint James the Brother of the Lord and the New Sinaitic Manuscripts], in Greek, (Hiera Mone Theovadistou Orous Sina paperback: 2006).

Casimir KUCHAREK, The Byzantine-Slav Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. Its Origin and Evolution (Alleluia Press, Allendalke, Canada: 1971).

MACARIUS of Jerusalem, Letter to the Armenians, AD 335, Translated by Abraham Terian (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, New York: 2005).

Subin John MATHEW, Tradition of St. James Liturgy as Unifying Ecumenical Liturgy for Worship (2011), Paper submitted to http://www.scribd.com/

Dom B.-Ch. MERCIER, La liturgie [grecque] de saint Jacques. Edition critique du texte avec traduction latine, Patrologia Orientalis XXVI, fasc. 2 (1946), pp. 115-256.

M.L. McCLURE & C.L. FELTOE, The Pilgrimage of Etheria, Translations of Christian Literature Series III – Liturgical Texts (SPCK, London: 1919).

-

MINGANA (editor), Commentary of Theodore of Mopsuestia on the Lord’s Prayer and on the Sacraments of Baptism and the Eucharist, Woodbrooke Studies, Vol. VI (Cambridge: 1933).

John Mason NEALE, A History of the Holy Eastern Church, Part I. General Introduction (Joseph Masters, London: 1850).

John Mason NEALE & R.F. LITTLEDALE (translators), The Liturgies of SS. Mark, James, Clement, Chrysostom, and Basil and the Church of Malabar, Second edition (J.T. Hayes, London: 1869).

John Mason NEALE, The Liturgies of S. Mark, S. James, S. Clement, S. Chrysostom, S. Basil: or, according to the Use of the Churches of Alexandria, Jerusalem, Constantinople, and the Formula of the Apostolic Constitutions, Third edition (J.T. Hayes, London: 1875).

E.C. RATCLIFF, “The Eucharistic Office and the Liturgy of St. James”, in The Eucharist in India. A Plea for a Distinctive Liturgy for the Indian Church” (Longmans, Green, London: 1920), pp. 41-69.

Thomas RATTRAY, Ancient Liturgy of the Church of Jerusalem being the Liturgy of St. James, Freed from all latter additions and interpolations of whatever kind, and so restored to it’s Original Purity: by comparing it with the Account given of that Liturgy by St. Cyril in his fifth Mystagogical Catechism, and with the Clementine Liturgy, &c (James Bettenham, London: 1744).

Eusèbe RENAUDOT, Liturgiarum Orientalium Collectio (London: 1847).

Alexander ROBERTS & James DONALDSON (editors), Liturgies and other Documents of the Ante-Nicene Period, Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Vol. XXIV (T & T. Clark, Edinburgh: 1872).

-

RŰCKER, Die syrische Jakobusanaphora nach der Rezension der Je’qob(h) von Edessa(Liturgiegeschichtliche Quellen, 4; 1923).

Lester RUTH, Walking where Jesus walked: Worship in Fourth-Century Jerusalem, The Church at Worship (Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, Michigan: 2010).

Sévérien SALAVILLE, An Introduction to the Study of Eastern Liturgies (Sands & Co, London: 1938).

Theodor SCHERMANN, “Die griechische Jakobusliturgie” in Griechische Liturgien by Übers von Remigius Storf, (Bibliothek der Kirchenväter, 1. Reihe, Band 5) (München 1912).

Bryan D. SPINKS, “The Consecratory Epiklesis in the Anaphora of St. James”, Studia Liturgica, Vol. 11 (1976), pp. 19-38.

Bryan D. SPINKS, “The Jerusalem Liturgy of the Catechese Mystagogicae: Syrian or Egyptian?” Studia Liturgica, Vol. 18 (1989), pp. 391-95.

C.A. SWAINSON, The Greek Liturgies chiefly from original authorities. Edited and translated by Dr. C. Bezold. (University Press, Cambridge: 1884).

Robert F. TAFT, The Great Entrance. A History of the Transfer of Gifts and other Pre-anaphoral Rites of the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Second Edition, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 200 (Ponificium Institutum Orientale, Rome: 1978).

André TARBY, La prière eucharistique de l’Eglise de Jérusalem, (Théologie historique 17, Paris 1972).

Phillip TOVEY, The Liturgy of St. James as presently used, (Alcuin/GROW Liturgical Study 13-14 (Grove Books, Cambridge: 1998).

-

TROLLOPE, The Greek Liturgy of St James edited with an English Introduction and Note; together with a Latin Version of the Syriac Copy, and the Greek Text restored to its original purity and accompanied by a literal English Translation (T & T. Clark, Edinburgh: 1848).

Kurian VALUPARAMPIL, “St. James Anaphora: An Ecumenical Locus. A Survey of the Origin and Development of St. James Anaphora”, Christian Orient, Vol. 8, Issue 4 (1987).

Baby VARGHESE, West Syrian Liturgical Theology (Ashgate, Aldershot: 2004).

Baby VARGESE, “Anaphora of St. James and Jacob of Edessa” in Ter Haar Romeny, Jacob of Edessa and the Syriac Culture of His Day, Monographs of the Peshitta Institute, Leiden (2008).

Stéphane VERHELST, “La Liturgie de Saint Jacques, Rétroversion grecque et commentaires” in Liturgia ibero-graeca Sancti Iacobi, Editio – translatio – retroversio – commentarii, Jerusalemer Theologisches Forum 17 (Aschendorff Verlag, Műnster: 2011).