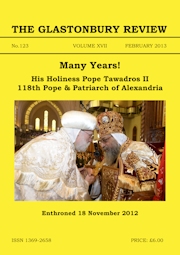

The Forgotten Patriarchate:

A Brief Historical Note on the Armenian Catholicosate of Aghtamar

Although evangelised by the holy Apostles Bartholomew and Thaddeus, the Church in Armenia was not finally established until the time of St. Gregory the Illuminator, who in 295 erected his episcopal see at the royal capital of Vagharshapat, later known as Etchmiadzin, under the shadow of Mount Ararat where Noah’s Ark came to rest. Seven years later the Armenian Church acquired its autocephaly from its parent See, Caesarea-in-Cappadocia, with the primacy established in the person of the Catholicos-Patriarch of all Armenia.

The subsequent vicissitudes of the Armenian kingdom resulted in the exile of the Catholicoi from Etchmiadzin and centuries of wandering from town to town. During the pontificate of Hovhannes V Patmaban (‘the historian’) 898-929, the first Catholicos to be forced into exile, the seat of the Catholicos was moved to the territory of the Artsruni family, whose head, Gagik Artsruni, had been appointed King of Vaspurakan by the caliph in 919 (an expanding Armenian state surrounding Lake Van) and, under their protection, established themselves on the island city of Aghtamar, two miles from the southern coast of Lake Van.

Aghtamar was no desolate retreat selected by the Catholicos for its isolation from civilisation, but a thriving walled-city built on the small island, with ornate palaces, gold topped churches and magnificent hanging-gardens over which the ancient chroniclers poured out wide-eyed and breathless descriptions, which did but poor justice to this island paradise. Here King Gagik had erected a fine new domed church, dedicated to the Holy Cross, which he offered to the Catholicos as his patriarchal Cathedral.

Gagik’s relations with Catholicos Hovhannes were not without some tension as the Catholicos had been a firm supporter of Gagik’s uncle, King Smbat I Bagatuni, whose beheading and crucifixion at the hands of the Muslim ostikan[1] Yusuf, was regarded as a Christian martyrdom. Gagik had failed to support King Smbat (890-914), which was seen as betrayal by many. Much of the Catholicos’ troubled thirty year reign had been spent mediating between the warring Armenian princes and Gagik’s brother and predecessor, Prince Ashot of Vaspurakan, had been excommunicated by the Catholicos shortly before his death in 904. It is also interesting that both King Smbat and his son, Ashot II (914-928) received a coronation and blessing from the Catholicos, whereas Gagik’s investiture was at the hands of the ostikan and not from the Catholicos, who pointedly described him as “crown-bearer” and “bearing something like a crown.”[2] Catholicos Hovhannes was certainly not a malleable ecclesiastic willing to bend to King Gagik’s will though scholars believes that the fact that his History shows a changing attitude towards Gagik, from being highly unfavourable in chapter XLIII to toleration by chapter XLVIII indicates a distinct softening of his attitude, probably marked by his removal to Aghtamar around 923/924.[3]

It is interesting, however, that his three successors, Stephanos, Theodoros and Yeghishe, were all princes of the Rshtuni family, whose Principality of Rshtunik extended along the south-western shore of Lakje Van, and whose ancestor, Theodoros Rshtuni (590-655), Ruling High Constable of Armenia, had built the first monastery on the island as long ago as 653. The Rshtunian Princes, who were now vassals of the Artsruni dynasty, were happy to make their home on the island, but under Catholicos Anania of Moks (946-968), who preferred the protection of the Kings of Arni, the patriarchal see was again transferred, having been in Aghtamar for only forty years (928-68).

After the departure of Catholicos Anania, Aghtamar fades out of ecclesiastical history until the twelfth century, by which time the Artsrunis and all other petty kinglets had been swept from their insecure thrones. The last King of Vaspurakan, Senekerim-Hovhannes (1003-1026), had ceded his kingdom, comprising some 72 fortresses and 3000-4000 villages, to the Byzantine Empire in 1021 in exchange for the city of Sebastea (Sivas) and its surroundings. Since 968 Aghtamar had been the seat of an archbishopric. In the Armenian Church bishoprics were largely based on noble estates rather than dioceses based on towns, and were largely held by members of the local noble family. Despite the migration of the Artsrunid king, his family, court and 14,000 retainers, cadet descendants of the family still owned the ancestral lands.

At the beginning of the twelfth century the current Archbishop of Aghtamar was Davit (David) Thornikian, a direct descendant of the Artsruni family. His father Abdelmeseh Khedenikian, a titular Byzantine curopalates (died 1121), was son of Thornik and descended from Khedenik, third son of King Gagik-Khachik of Vaspurakan .[4] Lands gifted to the church as waqf, an inalienable religious endowment, was an Islamic principal acceptable to the Muslim rulers, and if the church was always administered by a member of the family, they still retained considerable influence.[5] When Catholicos Barsegh I (1105-1113) fled from the Muslim rulers of Ani, he was offered refuge on Aghtamar and although he stayed for less than a year, the return of a Catholicos to Aghtamar raised the prospect of a more permanent return. At that period confusion in the church was rife and anti-patriarchs had recently been proclaimed in Honi and Varag. Before his death Catholicos Barsegh named a 20-year old youth, Gregory III Pahlavouni (1113-1166), as his successor, which provided the perfect excuse for Abdelmeseh Khedenikian to promote his son and return the Catholicosate to Aghtamar. Declaring Gregory’s enthronement illegal, a Synod comprised of Abdelmeseh and five local priests was held at Aghtamar at which Davit was elected and consecrated Catholicos in the Monastery of Zor. Despite the assembly of the Council of some two thousand, five hundred ecclesiastics, which condemned this ambitious prelate, the Archbishops of Aghtamar continued to style themselves Catholicoi, thereby establishing an anti-patriarchate.

For much of its history the Catholicosate was to remain semi-hereditary, usually descending from uncle to nephew, something with which Armenians were quite familiar as the earliest Supreme Catholicoi at Etchmiadzin were Gregorids from the Arsacid Dynasty descended from St. Gregory the Illuminator; whilst later in Artsakh the Hasan-Jalal dynasty supplied the Catholicoi of Gandzasar from 16th to the early 19th century and in Sis (Cilicia) the Catholicosate was semi-hereditary in the Adjaphian family. The Sefedinian family and their descendants, which reigned from 1288-1433 were actually of the Artsruni dynasty. Catholicos Stepanos IV’s grandfather was Sefedin Ark’ayun whose wife Marie, was the daughter of Khedenik, great-grandson of Catholicos Stepanos I. A khatchkar erected by him in 1340 declares, “I, Ter Stepanos, vicar of Aghtamar, an Artsruni by birth.” A Catholicos of the Gurdjibekian family, who in turn descended from the Sefedinians, reigned in the 15th century. Davit I appears to have reigned as Catholicos from 1113-1190, when he was succeeded by his brother Stepanos I, who had been married previously.

A detached chapel dedicated to St. Stephen was built on the south-east side of the cathedral in 1293 by Catholicos Stephanos III (1272-1296) who also repaired the crown of the dome, which appears to have collapsed at the end of the thirteenth century. His younger brother, Catholicos Zakaria I (1296-1336) is remembered as a builder and renovator. He built a domed church on the island of Lim, dedicated to St. George and a monastery attached to it. On Aghtamar he built two magnificent ‘oratories’, one for the winter and the other for summer, of which the one at the northeast angle still remains.

At its inception, the catholicosate of Aghtamar included within its jurisdiction the provinces of Siunik and Artaz (Macu) but by the 14th century it only included the dioceses of Ardjech, Khelat, Berkri, Khizan. One report dated 1345 stated that in 1345 the catholicosate comprised some fourteen dioceses. In the centuries following it shrunk and expanded according to changing circumstances, both political and ecclesiastical. Between the 16th and 17th centuries Aghtamar attempted to extend its jurisdiction over the dioceses of Van, Berkri, Ardjech, Khelat, Bitlis, Mouch, Khochap, right up to Amida (Diyabekir)

In 1393-1394, during the Mongol yolk, both Catholicos Zakaria of Aghtamar and Teodoros, the Catholicos of Sis, both were executed.[6] The circumstances of Zakaria’s martyrdom relate that one day he received a visit from a mullah, who wanted to give him a bag. Zakaria, suspecting his evil intent, advised him to take it elsewhere, whereupon the mullah struck the Catholicos. The monks rushed to the aid of the Catholicos to deliver him from the hands of the mullah. The mullah then deliberately tore out his own beard, injuring his face, before taking himself off to the Emir of Vostan to complain about the Catholicos and his monks. The Catholicos went himself to see the Emir, who was the taking his bath at the time, but the Catholicos was forced into the bathhouse and commanded to apostatise. When he refused, the Muslims fell on him, beat him, trample him and dragged him through the streets of the city until he passed away. Zakaria II was martyred on 25 June 1393.[7]

It is said that during Timur’s third raid he seized the leader of the Hakkari Kurds and imprisoned him on Aghtamar. These were tempestuous years for Armenian as the Mongols and Turks battled across the Caucasus. Timur’s son and successor, Shahrukh Mirza (1377-1477) led three campaigns against the Iskender, leader of the Kara Koyunlu (Black Sheep) confederation of Turkomans over a 15 year period, during which Armenian was subjected to devastation and plunder, to slaughter and captivity. One scribe, writing in 1425 records that some, “who had escaped to this God-protected island and placed their trust in God escaped from the captivity of the wicked tyrant.”

Three hundred years later, under Supreme Catholicos Hacob III (1404-1411), now resident in Sis, the opportunity arose for the two sees to become reconciled through the mediation of St. Gregory of Tatev (+1410), the great Armenian divine who had set himself the task of healing the schism. The Aghtamarian anti-Catholicos, Zakaria III (1434-1464), seeing the decline of the Supreme Catholicosate at Sis, and being anxious to uphold the traditions and reputation of his own see in the hope of enhancing its status, accepted the overtures and peace was grudgingly agreed to.

Motivated by men such as St. Gregory and others from the theological Institute at Siunik, the religious centre of the Armenian church, a spiritual renaissance took place, during which time it was agreed to move the catholicosate back to Holy Etchmiatzin, then under the comparatively secure overlordship of the Persians. Catholicos Gregory IX Mossabeguian (1439-1441) was reluctant to leave Sis, where the Catholicosate had been established since 1293 and preferred instead to abdicate his dignity. The archbishops of Sis, with the example of Aghtamar still clear in their minds, saw no reason why they should not also retain the exalted rank which their See had possessed for so long, and accordingly a second anti-patriarch was established at Sis.

The Armenian bishops, clergy and nobles who met at Etchmiatzin to elect a successor to Gregory IX were continually hampered by the rivalries of the chief ecclesiastics, and finally decided to ignore the power-seeking prelates and elect the saintly Kirakos of Virap out of the multitude of candidates who jostled for election. The three chief rivals: Zakaria, Catholicos of Aghtamar; Zakaria of Havootzthar (head of the Siunik Institute) and Gregory Jalalbeguian, Archbishop of Artsakh, finding themselves passed over, set about undermining the authority of Catholicos Kirakos (1441-1443) and asserting their own claims. Unable to exercise his office amid such rivalry, Kirakos resigned and the Catholicosate was again open to election.

Much to the annoyance of the ambitious Zakariah of Aghtamar, his rival Gregory Jalalbeguian was selected as Catholicos, taking the title Gregory X (1443-1465). Zakaria III was very much a warrior-Catholicos and on 26 February 1459 he had seen off a Kurdish attack on Aghtamar by Seyid-Ali, the chief of the Ruzaki Kurdish tribe from the province of Hakkari. The chroniclers tell us that “plundered the region of Gavash [south coast of the Lake Van] and despoiled the Christians of their possessions… After sending for two rafts from the village of Aghuna, he made preparations to land on the impregnable [island of] Aghtamar. He also threatened to put everyone there to the sword, to spill their blood in the sea, to demolish the holy churches, and to carry off the holy objects. But… the venerable and most virtuous Catholicos, the Lord Zakaria [III of Aghtamar], marched forth like a valiant general… to wage battle against the infidels. He seized the two rafts and brought them to Aghtamar, and thus the Christians were delivered from [the hands of] the infidels, who returned to their own places in shame.”[8] It is not surprising that such a prelate was unable to stand such an affront to his ecclesiastical ambitions, after years of careful plotting, Zakaria forcibly overthrew Gregory X and took possession of Holy Etchmiatzin (1461). However, Catholicos Gregory was not long in acquiring support and within the year the usurping Zachariah was chased back to his island see of Aghtamar.

Since the earliest times the possession of the mummified right art (‘the Soorp Adj’) of St. Gregory the Illuminator, had gone with the supreme ecclesiastical dignity, and with it the bishops performed the sacred rite of consecrating the Catholicos. Throughout the years of exile the catholicoi had lovingly carried the Holy Adj from town to town, confirming their title by its possession. Great was the consternation, therefore, which greeted the return of the Catholicos, when it was discovered, to everyone’s horror, that Zakariah had carried the Holy Adj as well as the sacred banner depicting Saint Gregory and King Trdat back with him to Aghtamar, to reinforce his claims. However, sympathisers of Zakaria suggest that he “rescued” the relic. A contemporary chronicler, the scribe Tumashay wrote:

“He entered the city of Van with numerous bishops, vardapets, and priests and multitudes of people with horses and horsemen. The priests, who walked both in front of and behind the banner, sang sweet melodies …. But the Baron who occupied the fortress of Semiramis, that is, the citadel of Van, namely Mahmut Bek, who was padishah Jihanshah’s foster brother, witnessing the prosperity of the Christians, wish to see the holy right hand, and he sent for it. When the great pontiff … entered the gate of the uppermost part of the citadel, the tyrant Mahmut Bek came out to greet him with all his chieftains and their families and with his sons. They fell down before the holy right hand and kissed it; and the offered supplications … The multitudes of the city and of the canton arrived every day with numerous gifts and offerings, and prostrated themselves before the holy right hand and greeted the great pontiff … Later he obtained … permission to proceed to his ancestral seat at Aghtamar stop when he left the city, multitudes of bishops, vardapets, and priests and all the corps of noble khojas of Van accompanied him, with their forces and armed horsemen. They arrived near the coastal city of Ostan. All of its inhabitants, priests and multitudes of people of all ranks, came out to greet them with incense and candles and resounding melodies; so much so that they were more than 1000 men in front of and behind the great pontiff. The ecclesiastical banner was carried in front, and the golden crucifix affixed on the top shone like a light … When the alien [Muslim] inhabitants of Ostan witnessed this rejoicing, they would deeply aggrieved by the splendour and by the forwardness of the pontiff [and they plotted against him, but he managed to flee] and the right hand of the Illuminator and, boarding a boat went to … The God-inhabited island of Aghtamar.”

Zakaria was confirmed as Catholicos of Etchmiadzin and Aghtamar by the Kara Koyunlu ruler, Jihanshah (1437-1465) as well as the local Kurdish emirs

In 1465 Stephanos V (1464-1469), the nephew and successor of Zakaria, went as far as to anoint his brother Smbat as the king of Armenia, “since” – according to one contemporary – “for a very long time the Armenian nation hasn’t seen a king”[9] By this act Stepanos implemented his uncle’s long-cherished dream of the restoration of an Armenian kingdom. Smbat’s sovereignty lasted for only a few years and incorporated only the Island of Aghtamar – which was at that time larger than now – as well as some other coastal territories. Nevertheless, Smbat stands in the history of Armenia as its last anointed and crowned King.

During the reign of Stephanos V of Aghtamar, the Holy Adj was successfully recaptured by Bishop Vrtanes of Odzop (1477) and triumphantly restored to Etchmiadzin; although the Catholicoi of Sis was soon to claim that they were also the possessors of the Illuminator’s right arm, which led them to assume the style, “Minister of the Right Hand of St. Gregory.”

According to the early sixteenth century traveller, the Venetian, Giovanni Angiolello (1451-c.1525),[10] Ismail, son of Sheikh Haider, sought refuge from the Kara Koyunlu ruler Rustum (1492-1497) on the island of Aghtamar in the 1490sd. There, at the age of thirteen he was crowned king at the hanbfds of an Armenian priest, after which he fled with his father to Karabagh. As Ismail I (1502-1524) he reigned as Shah of Persia and the first of the Safavid dynasty.

The mediaeval poet, Grigoris of Aghtamar (c. 1478-1550), author of “Concerning the Rose and the Nightingale” was Catholicos of Aghtamar.[11] His poetry is characterised by a deep love of the beauty of nature and the suggestion that the picturesque surroundings of Aghtamar was certainly fit to inspire a poet. An illustrated manuscript of The Alexander Romance dating from 1526 contains a colophon indicating that the copy was made from an exemplar provided by Catholicos Grigoris, who had edited the text of the exemplar. The scribe, Margaray, states that the Catholicos trained him in the art of painting, and notes that the illustrations of this present work were painted by the Catholicos himself.[12] During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the monastery at Aghtamar was clearly a centre of high Armenian culture. Among the members of the monastic brotherhood were Minasents Thovma vardapet (middle 15thy century), a well known singer and authority on khaz (neum) symbols as well as a scribe and historian; its scriptorium also produced the illuminators Zakaria Aghtarmartsi (14th century) – also a music and talented builder; Karapet of Aghtamar (15th century) and Zakaria, later Bishop of Gnuneats (16th century). Nerses of Aghtamar was a skilled musician, with a beautiful voice, and also as an orator, philosopher. When he went to Jerusalem during the time of Patriarch Hovakim (1775-1793) he approached the Patriarch after the church services to say, “The musician of Aghtamar is here.” When the patriarch learned that the speaker was Nerses he directed the choir to restart the church services. When the patriarch, the clergy and the people heard Nerses’ singing they were charmed by his voice and melodies. After the services the patriarch called Nerses to come to him, and he asked questions about the Bible. On receiving satisfactory answers the patriarch promised Nerses a silver chalice, candlestick and fan if he would remain at the St. Hagop monastery, but Nerses declined and returned to Aghtamar.[13] He is said to have written a book entitled “The Succession of the Catholicoi of Aghtamar.”

At the beginning of the sixteenth century an anonymous Venetian merchant who visited Aghtamar between 1510-1520 writes, “On the island there is a small city, two miles in circumference. The city’s limits are equal to that of the island. The city is called Armenik, very populous (about 600 houses) with only Armenians, no Mohammedans, and many churches.”[14] However, as the water level of Lake Van rose, the island shrank and became less significant.

During the pontificate of Catholicos Yeghiazar I (Eliazar) 1682-1691, Thomas I Doghlanbegian (1681-1698) from the village of Yerdj was consecrated as Catholicos of Aghtamar in Etchmiadzin, the first time the Supreme Catholicos had performed this sacred rite. Unfortunately the next Supreme Catholicois, Nahapet I (1691-1705) consecrated Bishop Awetis in 1697 and sent him to Aghtamar to replace Thomas. There is an interesting colophon in an illuminated manuscript ‘Directory of Feasts’ [Or.1384(5)] inscribed “Tovmas vardapet, Servant of Christ, 1697” and it is thought that the manuscript originally belonged to Awetis, but that he was outmanoeuvred by Thomas, who expelled him and retained his illuminated manuscript.[15]

The succeeding centuries furnished little record of the ecclesiastical history of Aghtamar, save the bare names of the catholicoi, its area having shrunk to the now depopulated island itself and the surrounding districts in the Kurdish mountains. In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, however, following the Russian occupation of part of the coast of the Caspian Sea in 1722, Armenians became hopeful of military support to liberate the Christians of Transcaucasia. A secret convention of Armenians, under the leadership of Ter Nerses, vardapet from Rushtunik, was held at the monastery of Lim in the north-eastern corner of Lake Van and long considered an impregnable fortress. During this convention the deputies took a ship by night to “the sea-surrounded inaccessible island” of Aghtamar to confer with Catholicos Hovhannes IV Dzoretzi. The Catholicos “willingly agreed to deliver his will by blessing the deputies who sincerely agreed to sacrifice their lives for the liberation of the province of Vaspurakan from the yoke of despots, and of pashas, and of beks and of aghas.”[16]

When Catholicos Thomas II (1761-1783) succeeded to the See he at first declared his independence, but later he submitted to the Supreme Catholicos and entered into negotiations about the succession at Aghtamar and relations between the two catholicosates. He is said to have constructed a ‘palace’ on Aghtamar and the large kavit or narthex erected on the west side of the Cathedral dates from 1763. We know also that the ancient monastery on the neighbouring island of Arter was restored by vardapet James of Batakan in 1766 but the community here was dispersed and James imprisoned and tortured in 1772.[17] When Thomas II died, the Brotherhood elected vardapet Karapet of the diocese of Van as his successor. Under the terms of the agreements between the two sees he should have been consecrated in Echmiadzin. However, a letter from the people of Aghtamar and of Van was addressed to the Supreme Catholicos Ghookas I (Loukas) explaining that because of unfavourable circumstances it would not be possible for Karapet to travel to Echmiadzin at the moment and asking that he might be consecrated at Aghtamar with the promise that he would proceed to his investiture at Echmiadzin at a later date. Catholicos Ghookas consented to this arrangement but Karapet neglected to keep his promise, which soured relations between the two sees. By 1788 the brotherhood had become dissatisfied with Karapet and Marcos was proclaimed Catholicos, with the support of Etchmiatzin. During the next fifty years there were some seven catholicoi, about whom little is known and their dates uncertain. Karapet II of Shatakh resigned in 1803 but appears to have resumed his functions in 1814 until his death in 1816. He is probably responsible for the erection of the belfry, crowned with a lantern, which is dated to 1790. Unfortunately this addition led to the destruction of the external staircase leading to the king’s gallery in the south exedra.[18] An illuminated manuscript dating from the time of Catholicos Haroutian (1816-1823) shows the Cathedral from the south in order to display its new belfry. According to an inscription in the tenth century monastery of Narak (Narakavank) – which was blown up by the Turks in 1948 – Catholicos Hovhannes V received his consecration at the hands of a Bishop Abraham. This Catholicos is recorded as having consecrated the Holy Myron in the presence of many pilgrims in 1832.

In 1843 when Catholicos Hovhannes V died, the Patriarchate of Constantinople seeing an opportunity to end the Catholicosate of Aghtamar, which had now become irrelevant as a separate hierarchical see, tried to prevent the Brotherhood from electing a successor. However, the Brotherhood, jealous of its privileges, and with the support of the local governor, Muhammed Khan, elected Bishop Khachator of Mokat as Catholicos. In response the Patriarchate of Constantinople obtained an Imperial edict deposing Khachatour, who was exiled to Shapinkarahisar in GiresunProvince on the Black Sea. However, he was soon able to return under an Imperial General Amnesty of Sultan Abdülmecid I, although unable to assume his pontifical functions.

In 1850 Layard of Ninevah, the celebrated archaeologist, passing through the province of Van, encountered Catholicos Khachatour II Mokatsi (1844-1851) returning from a St. George’s Day service at Narek. The Catholicos passed by riding on a mule and “dressed in long black robes, with a silken cow hanging over his head. Several youthful priests, some carrying silver-headed wands. followed close behind him”, whilst roundabout him thronged “a crowd of adherents … merry groups of Armenians returning from their pilgrimage”. Layard recalls that “he was on his way to the city (Van), and I thus lost the opportunity of seeing him at his residence on the sacred island.”

Crossing to the island, Layard was entertained at the monastery by an “intelligent and courteous monk named Kirikor .. a man of superior acquirements for an Armenian monk.” He found the Church and monastery in good condition with “a gilded throne for the patriarch near the altar” and noticed the elaborate carved tombstones of the Aghtamar Catholicoi, particularly that of Zachariah, which was “especially worthy of notice for the richness and elegance of its ornaments.”

The library of rare manuscripts of which he had heard, no longer existed, but the monk Kirikor assured him that many works of value had been removed to the capital some years previously by order of the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople. The monks obviously had a poor opinion of their Catholicos because they told Layard that he had obtained his nomination by bribing the celebrated Kurdish chief, Khan Mahmoud, within whose territory his followers mainly resided. Layard’s opinion therefore, was not likely to be very high, “the ecclesiastic who fills the office is generally even more ignorant than other dignitaries of the Armenian Church.”[19]

Following the death of Catholicos Khachatour II on 9 July 1851, Archbishop Gabriel Shiroyian, who served as Primate of Van, with the agreement of the clergy and notables, appointed vadapet Hachatoutr Shiroyian as locum tenens. As it was feared that Constantinople might again try to suppress the Catholicosate, they petitioned pleading for its retention, which they believe would avoid any disturbance and protest which they believed would ensure its suppression. This letter produced the desired effect and at its meeting on 28 July 1851 the National Council of the Patriarchate invited the submission of names of worthy and patriotic bishops to be elevated as Catholicos. The Brotherhood duly responded with a list of seven names, with Archbishop Gabriel’s name at the top. At a further meeting on 7 August 1851, the National Council decided that as Gabriel had been consecrated to the episcopate at Etchmiadzin, he could not become Catholicos of Aghtamar. However, the Brotherhood and people of Aghtamar disregarded this decision and named Gabriel as Catholicos. Constantinople finally agreed to his election and asked the Sublime Porte to sanction his appointment; but on 16 June 1852 Catholicos Nerses V of Etchmiadzin (1843-1857) criticised the Patriarchate for acting irresponsibly, rejecting Gabriels’s candidacy and reprimanding the Patriarch in Constantinople for not observing canonical procedures. Gabriel’s situation remained unclear and he continued to serve as locum tenens until 1856, after which he withdrew to his Prelacy of Van and died in 1857. However, it was during his time as locum tenens that Mkrtich Khrimian of Van, who was to become successively Patriarch of Constantinople (1869-73), Primate of Van (1880-85) and one of the greatest Catholicoi of All Armenians (1892-1907) was made a vardapet on Aghtamar.

After the withdrawal of Archbishop Gabriel the Catholicosate was administered by Hakob, Vardapet of Khizan, a member of the Aghtamar Brotherhood. The campaign to obtain Constantinople’s support for the election of a new Catholicos continued and in 1857 Bishop Sargis of Adrianople was proposed as a candidate on condition that his consecration as Catholicos should only take place after that of the new Catholicos in Etchmiadzin, which was then vacant. However, as this was delayed, Sargis withdrew his candidacy in January 1858 and the Patriarchate agreed to Bishop Bedros of Akhtamar, known as ‘Bulbul’, or nightingale, because of his sweet singing voice, to replace him.

In agreeing to this Constantinople imposed a new stringent concordat, which required that the Catholicos of Aghtamar must be approved by the Patriarchate of Constantinople; he must pay allegiance to the Supreme Catholicos in Etchmiadzin; he must not ordain bishops without the consent of Constantinople; he would pray for the Supreme Catholicos in the diptychs; he would ordain neither married noir celibate priests without permission and that the next Catholicos of Aghtamar would only be consecrated after the consecration of the new Catholicos in Etchmiadzin. This concordat was signed by two vardapets, one married priest and 18 lay deputies from Aghtamar. Despite all this, no time was lost and Bishop Bedros Bulbilian was consecrated as Catholicos of Aghtamar on 24 July 1858, which Macler says was performed by Bishop Thoros at the Monastery of the Maccabees[20] before the new Catholicos of Etchmiadzin, Mattheos I, was consecrated on 15 August 1858. To assert his independence and rejection of the imposed concordat, Catholicos Bedros I consecrated three vardapets, Khachatour, Ghazar and Hakob (Hovsep?), to the episcopate the day after his own consecration.

In the early 1860s another English traveller, John Ussher, visited Van and Aghtamar and met Catholicos Bedros II, whom he encountered at the nearby monastery of Aghavank. He describes him as “a man of middle age; not a gray hair could be seen in his jet black beard, which was of ample dimensions, and came down low upon his chest. The expression of his countenance and the brightness of his eye showed great keenness and acuteness, if not intellect.” The Catholicos was greatly interested in Ussher’s recent visit to Etchmiadzin and asked him many questions about “the number of monks, the size of the monastery, and more particularly the conditions and circumstances of the wealthier and more powerful ecclesiastic, whom he looked upon as a usurper” but when it came to Ussher’s turn to ask him about his own monastery and archiepiscopal see, its founders and antiquities, “he displayed the most profound ignorance.” He was much more interested in telling them about an inscribed stone slab with a long inscription in English in the monastery courtyard, which had caught the attention of Layard, “which he was told would, if conveyed to England be worth a great deal of money. He begged of us eagerly to look at it, and tell him what the writing on it meant, his manner at the same time indicating his readiness to sell the precious mass to us if we should desire to purchase it.”

Ussher and his companions were conducted to the monastery by one of the assistant bishops “on board a flat-bottomed boat, built, evidently by no boat builder, of thin boards of pine so crazy and frail that it was certain to go at once to the bottom if the water became rough.” Their voyage was delayed until the bishop appeared “carrying in his hands a cock and hen screaming loudly, which we at once divined was to form our dinner at the convent.” They arrived after dark and were accommodated in the bishop’s apartment which was “very small, but comfortable enough.” Ussher describes the monastery as consisting of a square, three sides of which were occupied by the cells of monks and other conventual buildings, while on the fourth was the church.” Having commented on the external carvings, Ussher describes the church interior as very poor, “A paltry gilt throne for the patriarch was placed near the altar, the walls being covered with frescoes in a desperate state of dilapidation, representing saints and martyrs, many of which were nearly obliterated, and hardly any uninjured.” They were shown several manuscripts, “two which, we were told had been copied by a Catholic priest who had remained for five months in the monastery for the purpose. Many more had been lately taken to Constantinople, but the greatest loss had been sustained at the hands of the Kurds, who destroyed many from sheer wantonness, using the covers in some instances to make soles for their boots.” On the steps of the church they examined the stone which the patriarch believed bore an inscription in the English and, to the disappointment of the monks, found it to be inscribed with cuneiform characters. The buildings round the court formed the apartments of the bishops, the cells for the monks, the storehouses, bakeries, etc. and were “of a most wretched and miserable description, of the same character as the huts in the villages we had passed through, to which they were by no means superior.” The Kurds, until within the last few years, were often in the habit of plundering the monastery, carrying away and destroying what ever the unhappy monks are unable to conceal. “Of church plate, furniture, and other usual appointments, it was thus completely destitute, the apartments being stripped of everything to the bare walls. We were told about forty monks and eight bishops belonged to the monastery, in which, properly speaking, they ought to live, but as at this time there was only room in the shattered and dilapidated buildings we have seen for a fourth of that number, the remainder, if indeed they really existed, must have been scattered about in the different villages.” Ussher’s experience led him to conclude that “the clergy under its jurisdiction are even more ignorant than their orthodox brethren, and a short interview which we had with the present occupant of the patriarchal chair did not tend to impress us with a very high idea of his intellectual attainments and culture.” While visiting Aghtamar they met only two bishops and four monks. Ussher visited the graveyard belonging to the monastery and commented on the tombs of the patriarchs and especially that of Catholicos Zachariah. When they left the monastery the monks assured them that, with the exception of the Catholic priest, only a couple of European travellers had visited the convent within the memory of anyone then resident within its walls.

The three bishops consecrated by Catholicos Bedros soon became his tormentors and by 1864 they plotted to depose him and replace him with one of their number. The Catholicos angrily withdrew from the island and returned to his paternal home in the village of B’shavank, neglecting his duties for many weeks. Learning of the plan to consecrate a new Catholicos, Bedros went to Akhavank on 25 September to confront the three bishops and attempted physically to stop them travelling to Aghtamar for the consecration, but was beaten by the crowd and forcibly removed from the boat, being thrown onto the shore of Lake Van wounded and covered in blood, as the rebellious bishops sailed off. He was carried back to his nephew’s house in B’shavank, but was killed three nights later, on 28 September, under the blows of a knife and a pistol. The culprit was said to be the Kurd, Giulkhan Bey, whom Macler calls the “faithful servant” of Khachatour, so suspicion fell on Khachatour Shiroyian, who had been consecrated Catholicos while Bedros was still alive but injured. When the news of these scandalous procedures reached Archbishop Inknadios, the Prelate of Van, he immediately appealed to the Governor of Van to declare the consecration as illegal and void, whilst the police arrested the murderers. Constantinople’s response was to refuse to recognize the canonicity of the procedures, although it was not until 22 July 1866 that the National Council declared the Catholicosate vacant and in October ofd the same year appointed Archbishop Inknadios as locum tenens.[21] Khachatour was summoned to Constantinople to be judged on 14 November 1866, but did not finally arrive there until 12 October 1868. The investigation dragged on for the next seven years, whilst the Brotherhood and people of Aghtamnar continued to demand that Khachatour be reinstated. Finally, on 4 December 1875 the Ecclesiastical Council under Patriarch Nerses II Varjabedian (1874-1884), put an end to the matter by declaring him free and innocent and recognising him as Catholicos of Aghtamar. He returned taking with him the Order of Mejidie, first class, issued by Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876-1909).

Khachatour had been born in the village of Poghanis, in the Rushduni canton of Van but early went to Etchmiadzin where he became a servant to a rich bishop. Patriarch Ormanian of Constantinople had a poor regard for his integrity, mentioning that he was guilty of thefts as he advanced himself. On receiving a substantial bequest at the master’s death he went to Aghtamar where he ingratiated himself with the Brotherhood and was ordained rapidly ordained a vartapet, and later a bishop.

Thanks to him, the region’s barbarous Kurds, such as Sheikh Jelaleddin, behaved in a mild manner with the unfortunate people of the parishes. Catholicos Khachatour, who was recognized as having administrative skills and a winning personality, began a much-needed programme of reconstruction; restoring buildings, including his residence on the island, the Patriarchate at Akhvank, to which a school was attached, as well schools, orphanages and a museum, where he gathered select manuscripts, some of parchment and with gold encrusted Mesropian letters, found dust-covered in the monasteries and the villages. He collected small and large stelae with cuneiform inscriptions, vessels, etc. It was said that had he had had competent advisors, he would have had more productive period of service.

Some thirty years later (1893) another English traveller, H.F.B. Lynch, passed through Armenia and left us with an unique account of the last years of the once proud Catholicosate of Aghtamar. Lynch found the Catholicos Khachatour III (1864-1895) living on the mainland at Akhavank in a “two storeyed white faced house, an upper room, built out, like a veranda, with large windows overlooking the lake; stables and appurtenances of various application – the whole relieved against a background of poplars and fir trees.” Inside the building “there are uncomfortable, rooms and passages alike. Full decadence was written large on the squalid furniture and cheerless walls … a fetid smell of garlic, and the want of ventilation, almost overpowered me.” At the end of a long apartment, squatting on a Kurdish rug, sat Catholicos Khachatour who spoke to him of the weight and cares of his office and his longing for the release of the tomb, “this touching sentiment is often used as becoming pretext for idleness by better people than Khachatour” is Lynch’s unsympathetic comment.

In reply to his enquiry why the Catholicos resided on the mainland rather than the island, Lynch was informed that the Catholicos was “in a better position to receive his guests and satisfy their wants”, of which Lynch caustically notes, “it is no doubt a paying business to keep such a monastery provided always that you manage it well. You must personally superintend the arrangements for the picnic, or others of lesser station will abstract your clients.” After a meal with the Catholicos, vividly described, Lynch set off for the island. Here he found the monastery much more decayed than it had been when Layard visited it, with only two monks in residence. Among the items which he notes is the already prepared tomb of Catholicos Khachatour, entreating, in its description, his people to be loyal to Sultan Abdul Hamid , whom he described as “the illustrious, because during my whole life I have found help from him and his high officers.” Lynch, however, found something in the library, albeit only five small shelves consisting of books and manuscripts mainly on biblical subjects.

When Lynch returned to Akhavank after his visit to the island he found the Catholicos where he had left him, squatting on his Kurdish rug, wearing a diamond-studied cowl, which enveloped the forehead, Lynch commenting, “Which, judging from the thick lips, flat nose and little eyes, was better hidden than revealed.” Not being particularly interested in discussing ecclesiastical matters, Catholicos Khachatour preferred to show Lynch his collection of “tawdry State orders and Firmans of Investiture some of which the Catholicos regarded with special reference, devoutly pressing them to his lips …” Lynch visited Aghtamar on 17/18 November 1893 and within two years, on the death of Khachatour on 24 December 1895, the See fell vacant, never again to be filled. A marble statue of the Catholicos by Khachig Kruzian, which had been blessed during his lifetime, was mounted on the grave, but has long since vanished. [22]

The role of locum tenens fell to the former Primate of Van, the able Archbishop Arsen Markarian, He did much to refurbish and renovate the catholicosate, and he visited the villages and the cantons where he opened schools. He made his pastoral visits, partly in the formal role as vice-catholicos, to impress the Kurds, and to take back most of the things they had been stealing. He succeeded, mainly in getting back precious manuscripts and enriching the library of the monastery. The manuscripts had been cataloged by Khachadur Levonian and Hovhannes Paraghamian. The island of Aghtamar and its monastery had succeeded in remaining unharmed during the Hamidian Massacre of 1896, thanks to the protection provided by the Kurd Murtala Bey.

Visiting the monastery in the summer of 1899, Earl Percy referred to the damage to the sculptures on the northern face of the Cathedral, “where the wall is riddled with holes from the rifle bullets of the Mukus Kurds who landed on the island four years ago, and finding that the monks had closed the church and fled to the hills for safety, wreaked their spite as best they could upon the exterior.”[23] When Earl Percy arrived at Akhvank (which he calls Pashavank) he describes the monastery there are as “a low straggling the farmhouse … close to the waters edge.” He and his companions were “hospitability greeted by the monks and regaled with dishes of cheese, honey, and clotted cream like pie-crust that had much the same flavour as tallow.” Inside the rooms contained hardly any furniture, and the walls were quite bare “except for a single all-length photograph of the old Catholicos, the rival of the potentate at Etchmiatzin, a most striking figure in his full vestments, with long white beard and dark meditative eyes.”

When they crossed to the island he describes the church as occupying “a rocky pinnacle at the eastern end of the island, rising above a long and low line of buildings in which the staff of the monastery are housed. About 40 of the monks lived here, and get their provisions from the mainland, where the remaining 60 members of the fraternity are stationed.” The belfrey at the western end led into the monastery square, where “the surrounding buildings, have a rude wooden gallery running the length of the two sides, and the roof is almost on the level with the base of the Western front of the church.” They were greeted in the courtyard by some thirty small boys, “dressed in grey jackets and brown felt hats” who were drawn up for inspection. The monastery maintained an orphanage with forty pupils and competent teachers. One of them was the brave armenologist, Hovhannes Paraghamian, a prize winner from Smyrna. The orphanage continued to serve until the Great Massacre of 1915.

Archbishop Arsen’s end took place in 1904. Tashnag Ishkhan and his band invaded Aghtamar and butchered Arsen and his secretary Mihran Kevorkian, driving them to the sea, having stolen Arsen’s ring and purloining his wealth. As justification they claimed that Arsen was responsible for a battle between the Ishkhan band and the Kurds.

In 1910 Archdeacon Dowling refers to the Catholicos as “the late Joseph” and mentions “Archbishop David, Son of Thornka, as Vice-Catholicos.” He has clearly become muddled about names and mentions the first independent Catholicos as if he were the current locum tenens. The splendid picture he reproduces as “Group Outside Akhtamar Cathedral” is actually of Catholicos Khachatour III and assisting clergy, taken on the Feast of the Holy Cross, 14 September 1890, and reproduced from the literary, artistic Revue, Arax, published in St. Petersburg in 1890.

Aghtamar was still a place of pilgrimage to devout Armenians and Oksen Teghtsoonian describes how he and his family stayed in the monastery guest house for two nights in August 1914 as part of a two-week pilgrimage, which included Narak monastery. Although the island itself was a “dry and desolate place” he refers to “luxurious fruit orchards, modern buildings and the Aghtamar monastery with its clergy, a bishop and a few vardapeds” as being on the mainland.[24] In 1915, the year of the Genocide, the remaining clergy suffered. We have an eyewitness account of this pitiless slaughter given by a Venezuelan mercenary serving in the Ottoman army, “As night was falling we passed the little island of Aghtamar, which seemed to possess no other edifice than an ancient and beautiful convent, where the Catholic Bishop of Van had lived. Its outer facades are adorned with allegorical pictures, which were barely visible from the launch through the gathering dusk. Apart from the corpses of the Bishop and the monks, huddled on thje threshold and atrium of the sanctuary, there seemed to be no human beings on the islet except the detachment of gendarmes which had slain the Christians. As they asked us urgently for some munitions, with which to seek out and kill God knows whom, we left them five thousands cartridges and continued the journey to the shore – which was outlined by the glare of burning villages that bathed the sky in scarlet.”[25] Two names, Bishop Hovsep Khosdeghyan and Vartabed Boghos Garabedian are given as having been martyred on Aghtamar although there are several other clergy killed in Van.[26] Possibly these included monks from the Aghtamar brotherhood seeking refuge in the Armenian Quarter of Van which staged a very successful resistance for about a month against the attacks of the Turkish army and civilians, and was finally rescued by Armenian volunteers serving as the vanguard of the Russian army.

Before the First World War the Catholicosate had consisted of some 70,000 members comprising 130 parishes, with 203 churches, covering the cazas of Gavash, Shatakh and Gardjhikan; whilst it also boasted one subordinate diocese of Khizan, which comprised of some further 25,000 members, in 64 parishes served by 69 churches.

Dr. Adrian Fortescue writing in religious weekly, The Guardian (11 November 1908) explains the relationship between the Armenian Catholicoi and Patriarchs, quoting an encyclical of the Catholicos of Etchmiadzin of 1890 address to “the blessed Catholicoi of the Houses of Cilicia (Sis) and Aghtamar, The Holy Patriarchs of Jerusalem and Constantinople, the Reverend Prelates of all our dioceses, etc.” describing himself as “over-Bishop and Catholicos of all Armenians, High Patriarch of the National Apostolic See of the Universal Mother Church of Ararat of Holy Etchmiadzin.”[27] Even Khachatour explained to Lynch that whilst he was quite independent of both Etchmiadzin and Constantinople” he was in the habit of consulting with the Patriarch of Constantinople on important matters. The Catholicos of Aghtamar had long been a moribund institution and under its last Catholicos “it had become more of an embarrassment to the Armenian Church than an asset”[28] so when the Armenian church patched up its bleeding wounds after the 1914-18 war it saw no reason for restoring it as is come to serve no special purpose, so in 1916 its history, jurisdiction and assets were subsumed in the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The Supreme Catholicoi exiled in Aghtamar: 929-951

Hovhannes V Patmaban 898-929

Stepanos II Rshtooni 929-930

Theodoros I Rshtrooni 930-941

Yesgishe I Rshtooni 946-968

From 951-1114 there were only Archbishops of Aghtamar

Line of Independent Catholicoi

David I Thornikian 1113-1165

Stepanos I Alouz 1165-1190

Stepanos II of Nkarten died 1276

Stepanos III Sefedinian 1288-1292

Zacharia I Sefedinian 1293-1336

Stepanos IV Sefedinian 1336-1346

David II 1346-1368?

Nerses I Polad 1369-1377

Zacharia II the Martyr 1369-1393

David III of Aghtamar 1393-1433

Zacharia III 1434-1464

Coadjutor in 1419 & anti-Catholicos in Etchmiadzin 1461-1462

Stephanos V Gurdjibegian 1465-1489

anti-Catholicos in Etchmiadzin 1467-1468

Zacharia IV 1489-1495

Atom 1496-1510

Hovhannes I 1510-1512

Gregory I 1512-1544

Gregory II 1544-1586

Gregory III the Young 1586?-1612?

Stephanos VI c. 1628

Martyros ?

Bedros I died 1670

Stephanos VII c. 1671

Philippos c. 1671

Karapet I died 1677

Martyros I of Moks 1652-1663

Hovhannes II 1669-1683

Tovmas I Doghlanbegian 1681-1698

Sahak I of Artzké 1698

Hovhannes III 1699-1704

Harrapet I Verdanessian 1705-1707

Gregory III of Gavache 1707-1711

Hovhannes IV of Haïotz Dzor c. 1720

Gregory IV of Hizan c. 1725

Paghtasar I of Bitlis 1735-1736

Nicholas I of Sparkert 1736-1751

Gregory V 1751-1761

Tovmas II of Aghtamar 1761-1783

Karapet II of Van 1783-1787

Markos I of Chatak 1788-1791

Theodoros I 1794-1794

Michael I 1796-1810

Karapet III of Chatak died 1803

Khachatour I The Healer 1803-1814

Karapet III of Chatak (restored) 1814-1816

Haroutiun I of Arton 1816-1823

Hovhannes V of Shatakh 1823-1843

Khachatour II of Moks 1844-1851

Bedros II Bulbilian 1858-1864

Khachatour III Shoroyian 1864-1895

Bibliography

Abrahamian, A., The Church and Faith of Armenia (Faith Press, London: 1920); Adalin, Rouben Paul, Historical Dictionary of Armenia (Scarecrow Press, Oxford: 2002); Akinian, Nerses, Gavazanagirk Gatoghigosats Aghtamara [Chronicle of the Catholicoses of Aghtamar], (Venice: 1920); Armenian Church Monthly – the Journal of the Armenian Church in America; Artsruni, Thomas, History of the House of the Artsrunik, ed, by R.W. Thompson (New York: 1991); Bachmann, Walter, Kirchen und Moscheen in Armenien und Kurdistan, (Leipzig, 1913); Bak, Janos M. and Banyу, Pйter, eds., Issues and Resources for the Study of Medieval Central and Eastern Europe (Budapest-Cambridge, MA: Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University and the Committee on Centers and Regional Associations of the Medieval Academy of America, 2001), “The Secret Meeting of Armenians on Lim Island in 1722 (Concerning the Possible Involvement of Western Armenians in an All-Armenian Liberation Movement)”; Bedrosian, Robert G., The Turco-Mongol Invasions and the Lords of Armenia in the 13-14th Centuries, Ph.D. Dissertation (Columbia University: 1979); Charick, M., (trans. Johannes Avdall), History of Armenia, two vols. (Calcutta: 1827); Cowe, S. Peter, Catalogue of Armenian manuscrtipts in Cambridge University Library (Louvain: 1994); de Nogales, Rafael, Four Years Beneath the Crescent (London: 1926); Der Nersessian, Sirarpi, Armenia and the Byzantine Empire – A Brief Study of Armenian Art and Civilization (Cambridge, Mass. 1945); Der Nersessian, Sirarpi, Aghtamar, Church of the Holy Cross (Harvard University Press: 1964); Dowling, T.E., The Armenian Church (SPCK, London: 1910); Gray, Charles, A Narrative of Italian travellers in Persia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (London: 1973); Hewson, R.H., “Arcrunid House of Sefedinian. Survival of a Princely Dynasty in Ecclesiastical Guise”, Journal of the Society of Armenian Studies (Los Angeles), 1 (1984), pp. 123-137; Hovannisian, Richard G., The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, 2 vols (New York: 1997); Hovannisian, Richard G., Armenian Van/Vaspurakan Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces (Costa Mesa, California: 2000); Encyclopedia of World Art, “Armenian Art”, Vol. I (London: 1965); Ipsiroglu, M.S., Die Kirche von Achtamar, Bauplastik im Leben des Lichtes (Berlin v. Mainz, 1963); Issaverdons, James, Armenia and the Armenians, 2 vols (Armenian Monastery, Venice: 1875); Jones, Lynn, Between Islam and Byzantium. Aght’amar and the Visual Construction of Medieval Armenian Rulership (Aldershot: 2007); Khachikian, Levon, Fifteenth Century Armenian Manuscript Colophons (in Armenian), Vol. 2 (1958); Kazanjian, Levon, Renaissance of Van-Vasburagan. Golden Age of Culture 1850-1950 (Boston: 1950); Layard, Austen H., Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon with Travels in Armenia, Kurdistan and the Desert (London: 1853); Lynch, H.F.B., Armenia, Travels and Studies, 2 vols (London: 1901); Macler, Frédéric, “Le ‘Liber Pontificalis’ des Catholicos D’Ałthamar”, Journal Asiatique, Vol. 202 (Paris 1923), pp. 37-69; Maksoudian, Krikor, Yovhannes Drasxanekertc’i’s History of Armenia (1987); Ormanian, Malachia, The Church of Armenia (London: 1910); Ormanian, Malachia, Azgapatum [History of the Armenian Nation], Vol. 3 (Sevan Press, Beirut: 1961); Percy, Earl, Highlands of Asiatic Turkey (London: 1901); Ritter, K., Die Erdkunde von Asien, Vol. X (Berlin: 1832-59, 2nd edit; Saint Martin, J., Mémoires sur l’Arménie, 2 vols (Paris: 1818); Sanjian, Avedis K., Colophons of Armenian Manuscripts, 1301-1480: A Source for Middle Eastern History, (Cambridge MA, 1969); Sanjian, Avedis K., A Catalogue of medieval Armenian manuscripts in the United States (Berkeley: 1976); Sarafian, Ara & Köker, Osman (eds), Aghtamar. A Jewel of Medieval Armenian Architecture/Ahtamar. Ortaçağ Ermini Mimarliğinin Mücevheri, text by Stepan Mnatsakanian (Gomidas Institute, London: 2010); Smith, Eli & Dwight, H.G.O., Missionary Researches in Armenia (London: 1834), Tchilingirian, Hratch, “The Catholicos and the Hierarchical Sees of the Armenian Church” in Anthony O’Mahony, ed., Eastern Christianity. Studies in Modern History, Religion and Politics (London: 2004); Teghtsoonian, Oksen, From Van to Toronto. A Life in Two Worlds (2003); Teotig, Golgotha of the Armenian Clergy (1921); Thierry, J.M. “Monastères Armeniens du Vaspurakan: Convent de la Mère de Dieu d’Artere”, in Revue des Études Arméniennes, Vol. XII (1977); The Times – 24 October 1964; Ussher, John, A Journey from London to Persepolis; including wanderings in Daghestan, Georgia, Armenia, Kurdistan, Mesopotamia & Persia (London: 1865).

Illustrations:

The Residence of the Catholicos at Aghavank

Source: Phaidra (Universität Wien) 190350

Bishops at Aghtamar Monastery

Source: Phaidra (Universität Wien) 190343

Catholicos Khachatour III, 1890

Source: Revue, Arax, published in St. Petersburg in 1890

Aghtamar Cathedral & Monastery, looking from the west

Source: Phaidra (Universität Wien) 188539

Aghtamar Cathedral & Monastery looking from the north west

Source: Walter Bachmann, Kirchen und Moscheen in Armenien und Kurdistan, Leipsig: 1913, courtesy of Vahé Tachjian, “Houshamadyan”.

The courtyard of Aghtamar monastery

Source: Eberhard-Joachim, Graf von Westarp, Unter Halbmond und Sonne, c. 1913, Berlin, courtesy of Vahé Tachjian, “Houshamadyan”.

Abba Seraphim

[1] A provincial governor under the Arab caliphate.

[2] Jones (2007), 25.

[3] Maksoudian (1987), Yovhannes Drasxanekertc’i’s History of Armenia (1987), 30, quoting M. Abelyan, Works III, 482.

[4] Adalian (2010), 110.

[5] Hewson (1984), 123-137.

[6] Bedrosian (1979).

[7] Macler, 51-52.

[8] Sanjian (1969), 263-264; Khachikian (1958), 117.

[9] Akinian 1920: 111; Khachikian 1958: 239.

[10] Gray ( 1973).

[11] Zabelle C. Boyazian, Armenian Poetry & Legends (1916) suggests an impossibly early birth date of 1418.

[12] Sanjian (1976).

[13] Mr. Yervant Der Mgrdichian has transcribed (see “Ardzvi Vasburagan,” No. 11, 1942) the colophon of the book “Havakadzo Antzants Gatoghigosats” by Ghazar Antzevatsi.

[14] Hovannisian, Van/Vaspuyakan, p. 128.

[15] S. Peter Cowe, Catalogue of Armenian Manuscripts in Cambridge University Library (Louvain: 1994), p. 116.

[16] Bak & Banyу, 59-68.

[17] Thierry (1977), 198-200.

[18] Sarafian & Köker (2010), p. 37 reproduces the excellent reconstruction of the entrance to the gallery of King Gagik bvy I.A. Orbeli.

[19] The tombstone of Catholicos Khatchatur II Mokatsi was still intact in 1956, but later smashed into fragments.

[20] Macler, 67

[21] Ormanian, (1961), par. 2679 & 2751.

[22] A biography of Catholicos Khachatour, written by Vartabed Hovhannes Kachuni, appeared in the journal “Araks,” 1897, Book 2, pp 51-61. Sarkis Sarian, father of the Armenian poet, Gegham Sarian (1902-1976), was the son of the sister of the Catholicos Khachadur of Aghtamar. Until the tragic events of ‘96 they lived in an opulent and princely manner, thanks to the catholicos. At the time of the ‘96 events, in order to escape certain death, Sarkis embraced the Kurdish identity, taking on the name of Khurshad. With the declaration of the 1908 Constitution, Sarkis resumed his Armenian identity. It was then that Gegham was born. But he became an orphan because his father was killed by the Kurds during the 1915 massacres. Gegham was taken to Yerevan where he completed his studies there and then went to Leningrad to teach. At the same time, he devoted himself to writing poetry.

[23] Percy, (1901), pp. 155-160.

[24] Teghtsoonian (2003).

[25] De Nogels (2003), 60.

[26] Teotig (1921).

[27] Tchilingirian (2004), 140-159.

[28] Hovannisian, Van