Little Spheres of Prophecy : Glastonbury, flooring, and the reign of Henry III.

1. William’s Floor

Around the year 1129 William of Malmesbury, a Benedictine monk of that Wiltshire house, arrived at Glastonbury, a sister Benedictine foundation some 50 miles away in the neighbouring county of Somerset, to study the books and documents of its ancient library and compose some saints’ lives for the Glastonbury monks. William, of mixed Anglo-Norman blood, was the greatest, indeed in the modern sense the only, historian Britain had produced since the death of the Venerable Bede in 735. Bede, for reasons concerning which we can but speculate, had made no mention of Glastonbury. William, in his Gesta Pontificum, the ‘Deeds of the Bishops,’ of c.1125, had suggested that the monastery had been founded by the West Saxon king Ine (688-726). ((Winterbottom, 2007, pp. 308-9; 534-5.)) Greater acquaintance with Glastonbury itself, however, convinced him that it was a pre-Saxon foundation, dating back to Roman times.

Like his exemplar Bede, William was conscious of the value of material remains – the archaeology, as we would say – in shining light upon the distant past. He tried to do what he could with the weathered inscriptions on two ancient cross-shafts in the monk’s graveyard. He was also impressed by a floor in the ‘Old Church’ of St Mary, the most ancient part of the monastery, the superstructure of which, when William saw it, was of wattle and daub construction protected by wooden planking, which in turn was weather-proofed with lead sheeting, for the building was conserved and venerated as in itself a holy relic. Of the floor, William writes (c.1135) in The Deeds of the Kings of the English:

The very floor, inlaid with polished stone, and the sides of the altar and even the altar itself above and beneath are laden with the multitude of relics. Moreover, in the pavement may be remarked on every side stones designedly interlaid in triangles and squares, and sealed with lead, under which if I believe some sacred mystery to be contained, I do no injustice to religion. ((Trans. Stephenson, 1854 (1989), (bk. 1, ch. 20) p. 20; Text, Mynors etc., 1999, pp. 804 -5: adeo pauimentum lapide polito crustatum, adeo altaris latera ipsumque altare supra et infra reliquiis confertissimus aggeruntaur. Vbi etiam notare licet in pauimento vel per triangulam vel per quadratum lapides altrinsecus ex industria positos et plumbo sigillatos, sub quibus quiddam archani sacri contineri si credo, iniuriam religioni non fatio.))

The same information is given almost verbatim in William’s monograph On the Antiquity of the Church of Glaston of c. 1129, which survives only in a revised mid-thirteenth-century edition. ((Scott, 1981, pp. 66-67; the authenticity of this section is not suspect.))

It seems clear that William is trying to describe a mosaic floor, something unfamiliar to him. Such pavements might be of the tessellated variety now best known by that term, in which designs were built up with small cubes of stone (or sometimes glass etc.) called tesserae, or of that popular in later Roman times, and continuing in Mediterranean Europe into the Middle Ages, known as opus sectile, ‘cut work,’ a kind of marquetry with larger elements of marble and semi-precious stone. ((A variety of this type named opus alexandrinum after the emperor Severus Alexander (222-235) employed mainly Egyptian purple and Spartan green porphyry. See Tatton-Brown, 1998, pp. 55-6.)) William’s account presents us with a problem. Although tiles, with decoration in polychrome relief, were laid in major churches from the later tenth century to the end of the Saxon period, ((Blackhouse et.al., 1984, pp. 136-7; Norton, 2002, p. 18 & n. 43, p. 26; Blockley, 1998, pp. 63-4.)) mosaic-work was not a feature of Anglo-Saxon building traditions. ((The Anglo-Saxon reference to a ‘coloured floor,’ fag flor, in the Beowulf (l. 725), is in the ‘antiquarian’ context of the legendary hall Heorot. The term recurs in place-names, e.g. Fawler, Berks., where it is considered to refer to Roman remains. See Wrenn, 1958 et seq., p. 198.)) Although the Normans commissioned mosaic in Italy, most notably in Sicily, in areas they took over from the Byzantines and Arabs from the 1060s onwards, they did not import it into Normandy or the British Isles. The rebirth of mosaic, both tessellated and opus sectile, in north-western Europe seems to have first occurred in the Rheinland and Flanders from the end of the eleventh century. ((Norton, 2002, p. 17 & n.40, p. 26; fig. 21, p. 81 (St. Bertin, St Omer, of mixed technique, c. 1109 or later).)) In England such ‘luxury pavements’ are not evidenced before the later twelfth century, with fragments of porphyry which may be from floors occurring at Old Sarum (where a pattern of mortar impressions of interlaced circles remained before the altar) and at St. Augustine’s, Canterbury. ((Tatton-Brown, 1998, pp. 57-8; Norton, 2002, pp. 9-10 & n. 11, p. 24.)) Had Glastonbury during the half-century preceding 1129 furnished a pioneering exception under one of its Norman abbots – Thurstan (c.1077-1096), whose soldiery had killed some of the English monks in a disturbance, or Herlwin (1100-1118), to both of whose building operations William refers, or Seffrid Pelochin (c.1120-1125), whom he notes as a donor of vestments and relics but not as a builder ((James Carley, 1996, pp. 17-18, in a passage which he admits is ‘highly conjectural,’ discusses the pavement in connection with the somewhat unconventional Seffrid, who went on to become Bishop of Chichester, only to be deposed for sodomy in 1145. He was buried with an antique jasper ring engraved with an image of the Gnostic god Abraxas (who also appears in mosaic at Brading, Isle of Wight).)) – then we might expect the fact to have been remembered within the community and mentioned by him. We should certainly expect this if the floor were a very recent work of that flamboyant builder Henry of Blois (brother of King Stephen, Abbot 1126-1171, and also Bishop of Winchester from 1129) to whom William dedicated his monograph on Glastonbury and whose building-work there he specifically praises. ((Scott, 1981, pp. 42-43.)) In describing Anselm’s new work at Canterbury Cathedral he mentions ‘the gleaming [or perhaps merely ‘polished’] marble pavements’ (perhaps an early use of Purbeck marble) in a quite casual manner. ((Gesta Pontificum, Winterbottom, 2007, p. 221: in marmorei pavimenti nitore. The contrasting use of the word stones (lapides) to describe the Glastonbury pavement might suggest it was tessellated.)) At Glastonbury he seems rather to imply that the floor was an ancient feature of the church, a part of its timeless mystery, and Christopher Norton, in the only detailed study to date of these early ‘luxury pavements’ in England, accepts William’s description as a ‘remarkable record of what appears to have been a pre-Conquest pavement surviving in the ancient Anglo-Saxon church,’ although without further analysis of its actual nature or date. ((Norton, 2002, pp. 10-11.))

William’s words are most easily explained on the hypothesis that the floor was, in fact, of Roman origin. Rodwell, 1998 (p. 41), notes ‘a few recorded instances of an in situ concrete or tessellated floor of Roman date being reused, where a church was built on the site of a more ancient structure (e.g. St Helen-on-the-Walls, York)’. Whether or not the documented late seventh-century Anglo-Saxon monastery at Glastonbury had a pre-Saxon phase, which might have been British (i.e. Welsh/Cornish), Irish or even Frankish in character, there is enough archaeological evidence to suggest that it stood on or adjacent to the site of ‘high status’ Roman buildings, almost certainly a villa. ((Finds include 1st- to 4th-century pottery, window glass, hypercaust tile, and probable wells. Now, Iron Age pottery, indicative of preceding settlement, and imported 5th- to 6th-century Byzantine pottery, has also been recognized in the Abbey assemblages (John Alan, 2011).)) We now know that there would be nothing very remarkable in this. In Gaul and other parts of the Latin West some villas seemingly evolved into later monasteries, but even in eastern England, where there is little question of institutional continuity, former Roman sites were very commonly chosen for church buildings, ((Percival, 1976, pp.178-9; 183-197.)) most spectacularly at Bradwell, Essex, and Reculver, Kent, where derelict forts were utilised. St Martin’s, Canterbury, famously used by Augustine’s 597 mission, incorporates elements of a Roman building. In mid-Somerset, Wells Cathedral had a late Roman or sub-Roman mausoleum at the heart of later Saxon developments, and at Cheddar, according to the excavator, the late Philip Rahtz, a Roman site adjacent to the parish church and to the important Anglo-Saxon and medieval palace-complex ‘may confidently be interpreted, especially in its later phases, as a “villa”’. ((Rahtz, 1979, p. 13. The site was excavated 1965-70.)) At Ilchester, the probable Saxon minster-church of St Andrew’s, Northover, stands within a late-Roman cemetery. Residual Roman material has been found in the churchyard of Holy Trinity, Street, where another villa-site has been suspected. On Glastonbury Tor, alongside the footings of medieval St Michael’s church, a grey limestone probable tessera was found, with Roman and Byzantine pottery and a quantity of Roman roof-tile. ((Rahtz, 1966, p. 48 (tessera), pp. 61-4 (pottery and tile). Mosaic floors of plain tesserae have recently (2010) been found at a villa site in Butleigh, Central Somerset Gazette, 26 Aug. 2010, p. 20.)) Reviewing the earlier data and the excavation plans published in 1966 by Rahtz, in a survey of the Tor carried out for the National Trust in 2001, Charles and Nancy Hollinrake identified the circular ground-plan of a probable Romano-Celtic temple on the summit. ((Talk to the Glastonbury Antiquarian Society, 22 Feb. 2002; see also Ashdown, 1988. The Hollinrakes, who have wide experience excavating at Glastonbury, have further suggested that in addition to William’s mosaic floor, the pink concrete opus signinum flooring discovered in early excavations of the Saxon churches, which stood further to the east, may here also be Roman work.))

As sealing with lead was not standard mosaic technique, either ancient or medieval, ((Norton, 2002, p. 25, n. 37, notes an early 14th-century pavement of stone stabs inlaid with lead at the abbey of Saint-Nicaise, Reims. On inlaid decoration on medieval floor-slabs see below.)) this feature in the Abbey’s ‘Old Church’ sounds like improvised repairs, perhaps made when the superstructure itself was encased in protective lead sheeting, lead being readily obtainable on the nearby Mendip Hills.

As William’s description of the floor is an aside to his main assertion of the numbers of saints’ relics everywhere interred, it seems that he intends us to understand the archani sacri, the sacred mystery, as residing in the design of the pavement rather than consisting literally of something buried beneath it. ((Although Mynors etc., 1999, pp. 804 -5, opt to render William’s words as ‘and I am not irreligious if I believe that some secret holy thing lies beneath them.’)) The interplay of square and triangle may call to mind the eight-pointed star, an ancient device very common in west-country Roman mosaic. ((See Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 32-33.)) In Somerset it occurs at Ilchester Mead, ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 228-9.)) Keynsham, ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 231-44; Johnson, 1987, pl. 35 p. 46.)) Lopen, ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 247-52; Webster, 2008, p. 153.)) Low Ham, ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 253-263, star at p. 256.)) Pitney (II), ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 286-7.)) Wellow, ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 292-96.)) Yatton ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 308-10.)) and at Hurcott, where it is repeated four times in an elaborate design. ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 212-13.)) At Bratton Seymour, Somerset, it frames a bust of (possibly) Diana ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, p. 196.)) and, more crudely, at Lenthay Green just south of the modern Somerset-Dorset boundary, a picture of Apollo’s musical contest with the satyr Marsyas. ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 161-2; Rivet, 1969, pl. 3.31.)) William makes no mention of any representational content which might (or might formerly) have reinforced his floor’s arcane message; neither does he tell us whether the floor’s mystic content was a deduction of his own, or whether others also recognised it, it being perhaps a subject of tradition. His allusiveness, reminiscent of his treatment of Glastonbury’s supposed apostolic origins, a legend which he acknowledges with scepticism, might perhaps suggest the latter.

Pavement at Hurcott

The range of esoterica which might be encountered in mosaic in the highly Romanised south-west of Britain was surprisingly large. Three overlapping ‘schools’ or workshops (officina) of mosaicists have been identified here, centred on Cirencester (Corinium), Gloucestershire, Dorchester (Durnovaria), Dorset, and Ilchester (Lindinis), Somerset. At Hinton St Mary, again just south of the modern Somerset-Dorset boundary, a beardless figure in a toga, the head nimbed with the chiro Christogram, has been seen as the finest fourth-century representation of Christ, not only in Britain, but in the entire Empire. ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 156-7. A minority view has seen the figure rather as a member of the House of Constantine, while Moorhead, 2000, has suggested that a coin of the (possibly half-British) usurper Magnentius (351-3) provided the actual model. For our purpose, it is irrelevant whether it represented Christ seen as a fourth-century emperor, or the emperor as the earthly image of Christ: the Christian content here is not in doubt.)) At Frampton, Dorset, some five miles (9 km) north-west of Dorchester, an elaborate scheme by the same ‘Durnovarian’ school of workmen, including the chiro, the cantharus (wine-mixing cup or chalice) and fragmentary texts, has been interpreted as symbolic of Christianity of an unorthodox, Gnostic, character, with Orphic and Dionysian elements. ((Perring, 2003, who also (p. 124, n. 160) makes the rather surprising statement that as the mosaics ‘described a form of grail quest, it is also possible to draw speculative connections between the allegories represented here and those subsequently incorporated in Arthurian legend (e.g. Weston, 1907).’ Few literary scholars would now take Jessie Weston’s analyses very seriously. The mosaics, now lost, were discovered and carefully drawn in 1794. Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 130-40.)) At Fifehead Neville, Dorset, a probable Christian mosaic featured a central cantharus surrounded by bands of fish and dolphins. ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 125-9; Rivet, 1969, pl. 3.30. Two rings with chiro bezels were also found at the site.)) At Lufton, Somerset, just south of Ilchester, the combination of cantharus and fish recurs. ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 269-72.)) At Bradford on Avon, two miles east of the Somerset-Wiltshire boundary, one wing of a double villa discovered in 2003 had been converted into a baptistery. In the main room, an octagonal font large enough to allow immersion had been built into an earlier mosaic floor, perhaps in the fifth century. In the adjacent apse the mosaic had been left intact, again featuring the eight-pointed star, here reinforcing the eightfold baptismal symbolism of the font, and two peacocks, in early Christian iconography symbolic of Christ, flanking a cantharus. ((David Derbyshire, The Daily Telegraph, 20.10.2003, p. 8, colour reconstructions by Alan Gilliland.)) Pagan mysteries are represented by a ‘Corinian’ workshop specialising in pavements with an Orphic theme, extending into Somerset at Newton St Loe with Orpheus and the beasts, ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 273-81; Rivet, 1969, pl. 3.10.)) while Bachus/Dionysius was the centre of a circle of deities at Pitney, Somerset. ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 282-5.)) More mainstream was the Dido and Aeneas floor, complete with nude Venus with cupids and a quotation from Virgil’s Aeneid, with which, around the year 350, the villa-owner at Low Ham, Somerset, demonstrated his easy familiarity with classical high culture. ((Cosh & Neal, 2005, pp. 253-263.)) A Roman origin for William’s mysterious mosaic, therefore, is entirely plausible and most surviving examples have been found no more than six to eighteen inches below the modern ground-surface.

2. Henry III at Glastonbury

After the glory-days of Henry of Blois’s abbacy, the Glastonbury community entered a difficult period which saw the beginnings of a long dispute with the diocesan authority, the bishops of Bath (the cathedra having been removed from Wells c.1090). To compound matters, in 1184 a disastrous fire destroyed the monastic buildings, including the fabled ‘Old Church.’ Such was the devotion to its ancient Marian cult that this was rapidly and exquisitely recreated in stone on the original site in the form of the still-extant Lady Chapel, which was consecrated in 1186, and a start was made on rebuilding the Great Church from its eastern end. The specific fate of William’s floor at this time is not recorded, but it might be thought unlikely that anything of it survived.

Financial difficulties followed the accession of Richard I, and at this stage Glastonbury’s long-standing associations with Arthurian legend found a concrete focus in the identification, c.1190, of some ancient burials in the churchyard as those of Arthur and his Queen; Glastonbury was now formally equated with the legendary Isle of Avalon. ((Glastonbury was already the scene of Guinevere’s abduction by the Otherworldly character Melwas in Caradoc of Llancarfon’s Life of Gildas of c. 1135, and appears as the Isle of Glass, a tradition of which ‘Avalon’ was a variant, in the poetry of Chretien de Troyes from c. 1170.)) This did not prevent its violent appropriation by the new Bishop of Bath, Savaric Fitzgeldwin, in 1193. To the despair of the monks, he united the abbacy with his office and began to style himself Bishop of Bath and Glastonbury. Savaric died in 1205 and was succeeded by Bishop Jocelyn. Glastonbury regained its formal independence from Jocelyn in 1219 in the so-called Peace of Shaftesbury, and William of St Vigor was elected as abbot. His successor was Robert of Bath (1223-1234, a candidate imposed by Bishop Jocelyn. In 1227 the traditional liberty of Glastonbury’s Twelve Hides (a mainly judicial area) was confirmed in Henry III’s name; ((Victoria County History, Somerset, vol. IX, p. 4 & refs. )) Robert’s former position as chaplain to Savaric, however, as well as the circumstances of his election, poisoned his relations with the community and he finally relinquished his office. It was only with the election of Michael of Amesbury as abbot in 1235 that Glastonbury began to feel itself completely free from the shadow of Bath and Wells – a situation which was not to last. Michael had previously travelled to Rome on the Abbey’s affairs and had good connections with the papal curia and the royal court. It was at this point that Henry III, whose personal rule had become effective in 1234, made the first of several appearances at the Abbey. ((The history of the Abbey in this period is conveniently summarised in Carley, 1996, pp. 21-31, and Dunning, 2001, pp. 41-2. It was Dr. Dunning (2006, p. 27) who first drew attention to Henry’s visits.))

Richard Foster engagingly sets Henry III’s reign (formally, 1216-1272) between the two great ceremonies of the translation of the relics of Thomas Becket to his new shrine in Canterbury Cathedral on 7 July 1220, which he witnessed but six weeks after his crowning (for the second time) at the age of thirteen at Westminster, and his own translation of the relics of Edward the Confessor to a new shrine within his rebuilt Westminster Abbey on 13 October, 1269, aged sixty-two. ((Foster, 1991, p. 8.)) It has been for his piety that one of England’s longest-reigning monarchs has been remembered, when he has been remembered at all, and after his death there was an abortive scheme for his own canonisation. Yet Henry was not devoid of political or military ambition. He sought long if unsuccessfully to regain the French territories lost by his father King John. He took the Cross in 1250, and his intention to go on personal crusade was initially genuine. He sought to strengthen the Plantagenets as a European dynasty by accepting for his second son, Edmund, a Papal offer of the throne of Sicily in 1254 (a brief and unhappy affair), and, more successfully, by securing the election of his brother, Richard of Cornwall, to the German throne as King of the Romans in 1257. As Dante noted, however, he gained a reputation for simplicity that was not wholly admiring. Much of his reign was spent as a pawn or virtual prisoner of powerful magnates. Dante placed him in that circle of Purgatory reserved for the ineffectual, and modern historians have been unwilling to dissent from this verdict.

Although Henry’s visits to Glastonbury in 1235 and 1236 were of a wholly casual nature, mere stop-overs in the wanderings of his court, they were seemingly the first by a reigning monarch since that of Cnut c.1032. ((Nitze, 1934, p. 356, invented a visit by Richard I to coincide with the exhumation of Arthur’s bones.)) The monks might have been forgiven for hoping they might presage a return to that royal favour which had sustained and enriched the monastery under the great pre-Conquest kings, among whom Edmund I the Magnificent, Edgar the Peaceable, and Edmund II Ironside had been buried at Glastonbury. If they did so hope, they were to be disappointed. Although Henry did indeed look to ground his kingship in the Anglo-Saxon past, it was in that least martial of monarchs, Edward the Confessor, that he found his inspiration, and the Confessor’s burial place, Westminster Abbey, which had been re-founded in the tenth century as a daughter-house of Glastonbury’s Dunstanian reforms, which from 1245 he sought to rebuild, beautify, and elevate to the status of the preeminent national shrine.

Henry III was a great traveller and famous for his pilgrimages to various English shrines, but the early years of his personal rule exemplify also the workaday peregrinations of the medieval royal court, in which administration was carried out very much on the hoof. It was in this administrative mode that he made various visits to Glastonbury during the abbacy of Michael of Amesbury (1235-1252).

He was in Glastonbury on 2 August 1235, having travelled from Wells, and granted certain quantities of timber to the Abbot of Glastonbury from the Forest of Cheddar and elsewhere. He was in Bath the next day, and in Malmesbury the day after that. ((Calendar of Close Rolls, 1234-1237, pp. 124-5.))

The 27 June, 1236 found Henry arriving at Glastonbury from Dundon. He made an order that an impartial jury be summoned in 15 days at the church of St John the Baptist to judge a land dispute between two private individuals and the Abbot of Osney, and dealt with further legal matters elsewhere in the kingdom. He was in Wells the next day, and at Bristol the day following. ((Calendar of Fine Rolls vol. III 1234-1245, p. 157; Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1232-1247, p. 151.)) The low-key nature of these visits doubtless explains why, unlike the set-piece ceremonial visits of Henry’s son Edward I in 1278, and his great-grandson Edward III in 1331 ((Watkin, 1947, pp. lxxiv-lxxv; see also Carley, 1996, pp. 43-4)) , with their respective queens, they left no trace in the Abbey’s own chronicles.

On 1 April 1243, while at Bordeaux, Henry granted an extension of St Michael’s Fair on Glastonbury Tor from two to six days, ‘on condition that it be not a nuisance to [other established] fairs.’ ((Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1232-1247, p. 370.)) The other fairs are likely to have been those of Wells, and perhaps significantly this was in the year following the death of Bishop Jocelyn of Bath. In 1245 his successor, Bishop Roger (‘of Salisbury’) ‘finally relinquished any claim to Glastonbury by adopting with papal approval the title of Bath and Wells.’ ((Dr. R. Dunning, pers. com..))

Henry’s return to Glastonbury in 1250 was a rather grander affair than his earlier visits, for in this year he spent the Feast of the Assumption, 15 August, with the community. This seems to have been, since Saxon times, the chief commemoration of Glastonbury’s ancient Marian cult. Henry arrived from Bridgwater on 14 August. He did not come empty-handed. On 2 August at Sherborne he had sent instructions to the keeper of the royal forest of Purbeck to admit Richard de Candevre the king’s huntsman ‘whom he is sending to take 8 stags there, to salt them well when taken, and to carry 3 to Merleberge [Marlborough] for the queen, and the other 5 to Glastonbury for the king against the celebration of the coming feast of the Assumption of St Mary.’ The keeper of the royal forest of Selwood was likewise instructed ‘to admit Henry de Candevre, the king’s huntsman, whom he is sending to take 40 bucks therein, to salt the venison, and to carry 5 bucks to Merleberge for the queen, and 7 to Glastonbury for the king against the feast of the Assumption.’ ((Calendar of Liberate Rolls, Henry III, vol. II, 1245-1257, London 1937, pp. 297-300.))

Henry’s concern with woodland and hunting matters continued. On 15 August in the sacristy of Glaston he granted three oak trees from the royal park at Periton (North Petherton) for the fashioning of ‘images’ for the church of Glaston. ((Calendar of Close Rolls, 1247-1251, p. 312.)) On 16 August he authorised a perambulation of the bounds between the lands of the Bishop of Bath and Wells in Cheddar and those of the Abbot of Glaston in ‘Audredes’’ (Andersey, now Nyland). ((Calendar of Close Rolls, 1247-1251, pp. 361-2.)) On 17 August, Henry moved on to Wells, where he granted certain exemptions from the harsh forest laws for the Abbot’s dogs and men in the royal forests. He moved on again to Chew and Bristol on 19 August. ((On behalf of the Abbot of Glaston. – The King has granted the Abbot of Glaston a respite with regard to the expeditation (expeditacione) of his dogs and men everywhere in his lands up to the following Michaelmas in the 34th year of our reign, and an order has been given to G. de Langel’ [an abbreviation], Justiciar of the Forest, to the effect that he is to permit the same Abbot and his men to enjoy the same respite. Witnessed by the King at Wells 17th day of August.’ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1247-1251, p. 313. Trans. by David Orchard, who notes that expeditation or hambling was the maiming of a dog by the cutting off of part of its forepaws of three toes’ width using a 2 inch wide chisel. This punishment for hunting in the Royal Forests rendered the hound useless for further hunting.))

Although the sources do not tell us so, it is also tempting to connect Henry’s visits with the completion of the rebuilding of the Great Church, and of the Galilee which linked it to the western Lady Chapel. In a recent review of the fabric, the architectural historian Jerry Sampson has argued that the church was substantially finished between c. 1235 and 1250, by which date it was roofed, although not yet vaulted. ((Talk to Glastonbury Antiquarian Society, 28.10.11 & pers. com..))

To the sadness of his monks, Michael of Amesbury retired with failing eyesight in 1252, and died the following year. He was succeeded as abbot by the already elderly Roger of Ford (1252-1261), Glastonbury-born and a scholar, author of a Mirror of the Church (MS BL Cotton Tiberius B. xiii), but a more political figure than Michael had been, and less popular with the monks.

The years 1253 and 1254 saw Henry campaigning in Gascony, the marriage of Prince Edward to Eleanor of Castile, and, in February 1254, the abortive plan for Edmund Crouchback, Duke of Lancaster, Henry’s second son, to take the crown of Sicily from the Hohenstauffens. In December 1254 Henry was personally able to visit, and marvel enviously at, Louis IX’s Sainte-Chapelle in Paris (see below). In Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Gwynedd launched a widespread revolt in November 1256 which was to drag on for a decade. Henry’s scheme to install his crusading brother Richard of Cornwall on the German throne, however, bore fruit when he was crowned King of the Romans at Aachen with all the panoply of the Reich on Ascension Day, 17 May 1257, ((Roche, 1966, pp. 137-8.)) although he never went on to Rome for a second coronation as Kaiser by the Pope. This is the background against which, on 2 July 1257, we see Abbot Roger of Glastonbury ‘going beyond the seas as an envoy of the king.’ ((Calendar of Patent Rolls 1247-58, p. 568. )) January 1258 saw him again appointed ‘as the king’s proctor in the court of Rome to obtain privileges and indulgences.’ The 7 May 1258 found him still ‘gone to the court of Rome on the affairs of his Church.’ ((Calendar of Patent Rolls 1247-58, p. 628.)) That year, 1258, however, saw the political coup which effectively ended Henry III’s personal rule.

3. The Holy Blood

The late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries saw a marked growth of the empathetic contemplation of Christ’s sufferings within Western piety, combined with an emphasis on the sacrificial nature of His death and on His True Presence within the consecrated bread and wine of the Mass. This doctrine of transubstantiation was defined for the Latin Church as a requirement of the Faith by the Lateran Council of 1215. The True Presence received its own commemoration in 1264 as the Feast of Corpus Christi, literally, the ‘Body of Christ’, which became everywhere a great popular celebration of late-medieval devotion.

In 1239, the pious French king Louis IX, husband of Henry III’s wife’s sister, purchased what he believed to be the veritable Crown of Thorns from his cousin Baldwin, the crusaders’ impoverished Latin ‘Emperor’ of Constantinople. In 1241 Baldwin further sold him a portion of the True Cross and other relics (including a portion of the Holy Blood) which Louis and his brother paraded through the streets of Paris, all recorded in England by the St Alban’s chronicler-monk Matthew Paris, who acted (not uncritically) as a propagandist for Henry III. An exquisite Gothic church, the Sainte-Chapelle, was built to house these relics within the palatial complex on the Isle de la Cité. Work had begun by 1244, and the chapel was formally consecrated in April 1248. Although he was not himself to have the opportunity to set eyes upon it until 1254, when it was said that he wished he could take it home in a cart, the construction of this French royal shrine became an immediate spur to Henry’s plans for Westminster Abbey.

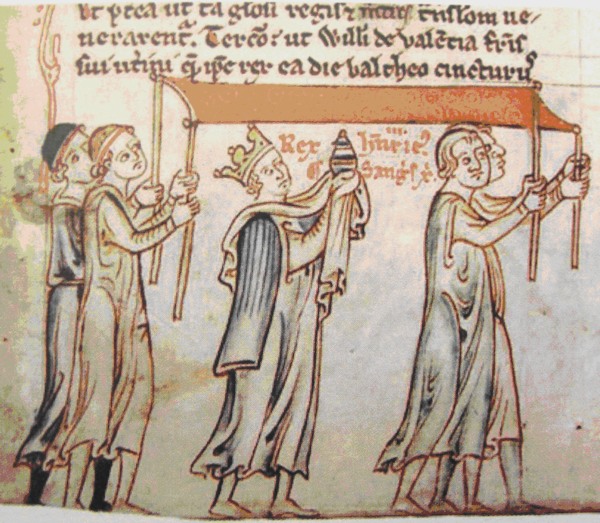

It was doubtless in this knowledge that in 1247 the much-beset Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Robert of Nantes, a Breton currently living in exile at Acre following the fall of Jerusalem to Islam in 1244, sent Henry a ‘crystal pyx’ (pixide cristallina) containing, he alleged, a portion of the Holy Blood, along with a letter drawing attention to the difficulties of the crusader-church in Outremer. ((Vincent, 2001, pp. 202-4 and passim. What follows is based mainly on Vincent’s account, the only comprehensive study of Blood Relics in English.)) If the Patriarch hoped to gain material assistance from Henry in return, he was doomed to disappointment. Henry, however, was delighted with the gift. On St Edward’s Day, 13 October 1247, he himself, dressed in simple clothes, bore it on foot beneath a pall stretched between four spears from St Paul’s Cathedral to Westminster, where, at Henry’s command, all the lords spiritual and temporal had gathered to witness the event. Henry carried his relic through all the rooms of the palace before installing it in the Abbey. He drew the chronicler Matthew Paris aside and gave him special instructions to record everything in detail, which he did in both words and in a drawing. Paris records that on St Edward’s Day in both 1248, and 1249, the relic was displayed to unparalleled devotion. He may have exaggerated, however. Like the cult of St Edward the Confessor itself, the Westminster blood-relic failed to find any permanent place in popular devotion and was soon forgotten.

Another of its kind fared rather better. In 1269 Henry’s nephew Edmund of Cornwall, son of that brother whom he had placed on the German throne, returned from Germany with a relic of the Holy Blood, part of which he gave to the Cistercian Abbey of Hailes (also spelled Hayles) in Gloucestershire, founded by his father, in September 1270, and part (eventually) to the college of Bonhommes at Ashridge in Hertfordshire which he founded c.1283. Although its origin was only vaguely known and remembered at Hailes, it seemingly derived from the store of imperial relics and regalia then housed at the castle of Trifels in the Rheinland, which included the renowned Holy Lance, believed to have pierced Christ’s side. ((See Vincent, 2001, pp. 137-51; 206-8. The German regalia were subsequently kept at Castle Karlstein in Bohemia before removal to Nuremberg in 1423. They were taken to Vienna to safeguard them from Napoleon, where, but for a return to Nuremberg from 1938-45, they have been ever since.)) The popularity of the Blood of Hailes as a magnet for pilgrimage became proverbial, and despite the fact that at the Reformation it was denounced as the blood of a duck, the saying ‘as sure as God’s in Gloucestershire’ was recorded from the seventeenth century as perpetuating its memory.

The English reigns of Richard I and John and the first half of that of Henry III also coincided with that great upsurge in the literary evolution of the Arthurian legend centring on the theme of the Holy Grail. This cultural phenomenon was in large part, no doubt, a reflection of the theological developments noted above. It was the genius of the French writer Robert de Boron which gave the Matter of Britain a cosmic dimension, which ran from the Fall to intimations of the Millennium. He did this by identifying the Grail (first referred to as an enigmatic dish in Chretien de Troyes’s Perceval or Le Conte del Gral of c.1190) unambiguously as a Passion Relic, a vessel of the Last Supper, and by invoking the New Testament figure of Joseph of Arimathea as an intermediary in its passage to Britain. That Glastonbury played some part in Robert’s projected scheme from the beginning seems clear from his naming, in his verse Joseph d’Arimathie (c.1200), of the ‘Vales of Avaron’ (vaus d’avaron, usually agreed to represent Avalon) as the eventual destination of the Grail-bearers. William of Malmesbury’s Deeds of the Kings, with its acknowledgement of Glastonbury’s apostolic foundation legend and other mysterious matter, was well-known on the Continent, offering a potential starting-point for this idea. Robert’s planned verse-trilogy remained unfinished, however, and its themes were developed by other hands. The only slightly later, anonymous, Perlesvaus (c. 1200-1210) is intimately connected to Glastonbury and, although not named there, Glastonbury-related matter may also be detected in the so-called ‘First Continuation’ of Chretien’s Perceval and in the Vulgate Cycle (c. 1215-1230) of Arthurian romance which built upon that of de Boron. The romantic fictions of the French Grail-writers, however, stand at some remove from the house-traditions of Glastonbury Abbey itself. The earliest surviving text of William of Malmesbury’s On the Antiquity of the Church of Glaston, in Trinity College, Cambridge, Manuscript R.5.33, incorporates extraneous matter and glosses of various dates into a coherent whole, probably by the hand of Adam of Domerham (now Damerham, Wiltshire), and dates from 1247. Adam then initiated a continuation of William’s history to the year 1291 known as the Libellus. ((Ed. Standen, 2000. William’s original content may be largely reconstructed from his abridgement of its matter into the third edition of his Deeds of the Kings of c.1135.)) In the 1247 re-working of William’s chapter one we first find Joseph’s name – somewhat soto voce – included in an official Abbey history, which notes ‘it is said’ that he was appointed as leader of the nameless apostles who were long believed to have founded Glastonbury. ((Scott, 1981, pp. 44-45.)) Although the Abbey henceforth claimed foundation by Joseph, it never went so far as to claim for itself the Grail, howsoever understood. In an early footnote added to the 1247 text, the literature of the Grail is cited, but only as a kind of aide memoir of passing interest. No claim is made that these fictional accounts are true. ((Scott, 1981, pp. 46-47; 186. These notes were, however, incorporated by John of Glastonbury into the text of his Chronica, Carley, 1985, pp. 52-53.)) The Abbey can hardly have been pleased, however, by Henry III’s grand ceremonial donation of the Holy Blood to Westminster in that same year of 1247.

Henry III processes with the Holy Blood

Cults of the Holy Blood were not without controversy within the Church. Conservative opinion (eventually upheld by Aquinas) held that the bodily substance of Christ had all been subject to Resurrection and Ascension, none remaining on earth, and holy foreskins, umbilici and blood were regarded with widespread scepticism. To counter this view, Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln and Britain’s most learned intellectual of the day, wrote in 1247 a ‘determination’, a sermon or tract in defence of Henry’s relic. His detailed arguments, which involved the different types of blood posited by contemporary medical theory, need not concern us, but he offered a supposed history of the relic which clearly depended on the contemporary Grail-literature and is illustrative of the speedy diffusion in England of the de Boron-derived story of Joseph of Arimathea. Grosseteste himself had tried his hand at verse romance with his allegorical ‘Castle of Love’ (Chateau d’Amour) in which the ‘castle’ is the Virgin Mary. In his tract De Sanguine Christi (On the Blood of Christ) ((Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, vol. vi, Additamenta (ed. Luard, Rolls Ser.), pp. 138-144.)) he asserts that Joseph first attempted to wash the blood from the Cross and Nails, then from the various wounds. The most precious was that from Christ’s right side (the Spear wound) which he placed in a noble vase. Of the lesser kinds, mixed with the water from the washing, he gave some to friends as medicine. ((Grosseteste, interested in medicine, may have based this detail on the medicinal use of particles of the dried blood of Thomas Becket (martyred 1170) mixed with water (see Vincent, 2001, pp 45-6).)) He also gathered Christ’s sweat, which fell like drops of blood at His arrest (Luke 22:44). These relics were passed down among his descendents and came eventually into the unlikely hands of the Latin patriarch, Robert of Nantes. The Patriarch himself had merely asserted that the Blood came from the treasury of the Holy Sepulchre. It is notable that in contrast to the older legends of the blood-relics preserved at Lucca in Italy and Fecamp in Normandy, it is Joseph, and not his New Testament companion Nicodemus, whom Grosseteste casts as the principal player.

At Hailes, an early fourteenth-century metrical re-telling of the history of the blood-relic there held that it had been collected at the Crucifixion by an anonymous Jew who was subsequently imprisoned for forty-two years; the relic then passed via the emperors Titus and Charlemagne to the treasury of the German Kaisers. ((Vincent, 2001, p. 141 & refs..)) This is the story of Joseph, as told in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus and elaborated in the French Grail literature, and the omission of his name can only have been intended to distance the Cistercians’ relic from Glastonbury’s claims.

It seems likely that Grosseteste’s tract, which set out to make the stuff of romance acceptable in theological terms and within a church setting, determined the detailed forms in which Glastonbury’s developed Arimathean legend eventually expressed itself. The introduction of Christ’s sweat, and the detail of the vase, presumably reflecting Henry’s crystal pyx, are diagnostic here. As we shall see, Glastonbury was to claim that Joseph had brought two ‘white and silver’ cruets, containing the blood and the sweat of Jesus, which were concealed within his conveniently hidden tomb there, assertions doubtless intended to match the royal cult of the Holy Blood at the rival Benedictine house of Westminster after 1247, and that of the much closer Cistercian pilgrim-church of Hailes after 1270. Both Grosseteste’s defence and the metrical Hailes legend, however, hinge ironically upon established Arimathean literary tradition which was properly more appropriate to ancient Glastonbury, as in the work of Robert de Boron.

Blood-relics might be of various kinds. Eucharistic blood-relics were communion wine which was alleged to have tangibly become actual blood. Effluvial relics derived from hosts, icons, or statues which miraculously bled. The classic instance was a Beirut icon which was said to have done so when mistreated by Jews in 765. To this Glastonbury had its own parallel in the form of a silver crucifix which had allegedly bled when struck by an arrow in the altercation of 1070 between the Saxon monks and the henchmen of their Norman abbot Thurstan (referred to above). An otherwise unregarded Glastonbury blood-relic, mentioned in a fourteenth-century relic list, may perhaps relate to this incident. ((Carley & Howley, 1998, p. .)) Most valued, however, was blood allegedly shed in the Passion itself, such as that of Westminster and Hailes.

In his survey, Nicholas Vincent finds the earliest reference to blood-relics of the Passion in Western Europe in Gothic Spain in a letter of Braulio, Bishop of Saragossa, written in 649 or 650, in answer to the enquiry of a certain Abbot Tajo, who had recently returned from Rome. ((Vincent, p. 53; Barlow, 1969, pp. 88-95.)) Braulio acknowledges that some cathedrals were said to posses such relics ‘although they have never been found in my church [of Saragossa] in the time of any bishop.’ Braulio somewhat grudgingly allowed the possibility that the blood and sweat of Christ might have been scraped from the pillar of the scourging in Jerusalem. ‘It is possible that many things happened then which have not been written down, just as we read of the linen cloths and the shroud in which the body of Christ was wrapped, that they were found, yet we do not hear that they were preserved; yet I do not suppose that the apostles neglected to save these and other such things for future times.’ ((Barlow, 1969, p. 93.))

Vincent also cites a contemporary inscription at Guadix, southern Spain, which might refer to such a blood-relic. ((Vincent, 2001, p. 53. )) Given the links between the western British Isles and Spain at that time, it is interesting that a reference missed by Vincent is to be found in the Liber Angeli, the ‘Book of the Angel’, a part of the so-called ‘Patrician dossier’ preserved in the Irish ‘Book of Armagh’ of 807. Its date of actual composition has been disputed, but may be as early as the late seventh century. It states that:

To remind us of the holy wonder of [God’s] unspeakable gift to us there is [at Armagh] by a secret dispensation [a relic of] the most holy blood of Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of the human race, in a sacred linen cloth, together with relics of the saints in the south church, where rest along with Patrick the bodies of holy pilgrims who came from afar, and other just men from overseas. ((Trans. Hughes, 1966, p. 278.))

Glastonbury, from the early tenth century at the latest, was a centre of Irish influence in England. It claimed relics of St Patrick, a claim acknowledged by some Irish sources, and attracted Irish pilgrims of sufficient status to donate books to its library. By the twelfth century Patrick was regarded as founder of the monastic community which eventually grew up around the ‘Old Church’. In taking over the role of founder in the High Middle Ages, Joseph of Arimathea, who shares his saint’s day with Patrick, appears to have adopted other features of Patrick’s cult. This may even extend to the famous Christmas-flowering Thorn, for there was once in France (at St Patrice, Dept. of Indre-et-Loire) an Espine d’Saint Patrice which similarly flowered at the Nativity. It may be that the association of a founder with a blood-relic, a portion of Christ’s burial cloths, and righteous pilgrims from overseas, represents another such borrowing. In the grail-romance Perlesvaus, the hero’s sister Dindrane is allowed to take a portion of Christ’s shroud which is preserved as an altar-cloth in a chapel which is transparently a fictionalisation of Glastonbury’s ‘Old Church’. ((Accessibly, Bryant, 1978, pp. 142-147 (= S. Evans, High Hist. Holy Grail, 1898, vol. i, pp. 280-92).)) The precise mechanisms by which Joseph of Arimathea entered the Glastonbury mythos are still far from clear, and scholarly accusations of ‘monastic fraud’ and ‘appropriation’, derived as they are from older Protestant historiographical rhetoric, are unhelpful and serve only to further obscure complex and subtle processes.

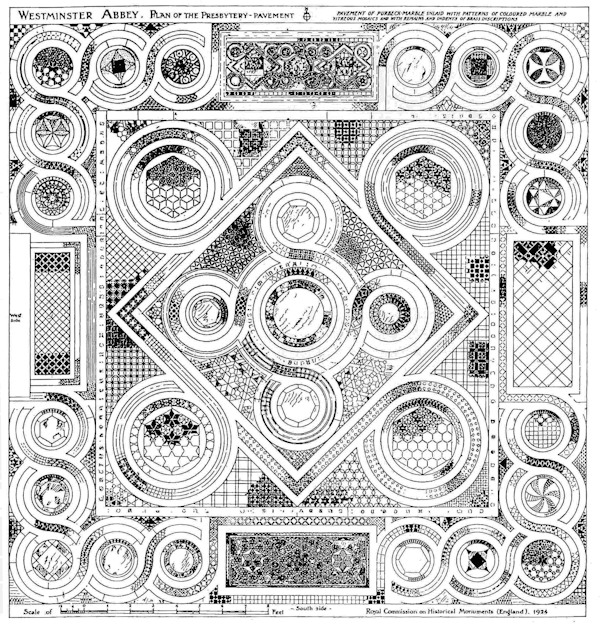

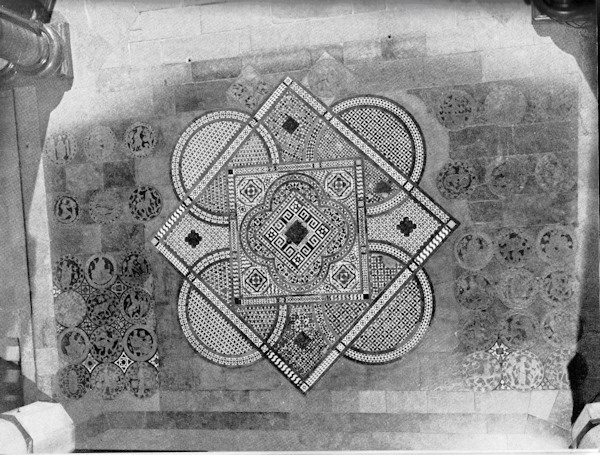

4. Henry III’s Cosmati Floor

Late in 1258 the newly elected Abbot of Westminster, Richard de Ware, left for Italy for confirmation of his office by the Pope, returning the following summer. The Papal court was resident in March 1259 at Anagni, where Ware was made a papal chaplain. Here, or so the theory goes, he was impressed by the cosmati-style mosaic pavement of the cathedral and conceived the possibility that his own abbey church might be similarly beautified. Named from the Cosmati, one of its leading families of exponents, such work was a style of opus sectile utilising recycled antique marble, porphyry, and other semi-precious stone elements. As well as floors, the cosmati craftsmen decorated altars, screens, tombs, candelabra, thrones etc. with their geometric designs of rectangular panels and of roundels linked by curving bands in a swirling chain-effect. Ware revisited the papal court in early 1260 and again in early 1261, ‘on the affairs of the king and the church of Westminster.’ It is on these visits, doubtless following extensive discussion with the King, and probably with the assistance of the Pope, that Ware is likely to have acquired a varied selection of suitable stones and arranged for Italian workmen to accompany them to Britain, chief of whom was Peter Odericus, a ‘citizen of Rome’. ((As noted on Henry’s tomb. This account follows Carpenter, 1996, p. 421 (with refs.).))

The Westminster sanctuary pavement was substantially completed in 1268, the year before Edward the Confessor’s relics were translated to their new shrine. The cosmati work at Westminster also included the base of Saint Edward’s shrine, its altar and the paving around it, and several tombs, including that of Henry III himself for which Italian craftsmen returned around 1278-9, although the preservation of these is only fragmentary. The sanctuary pavement, however, is not merely the only Cosmati floor north of the Alps but also one of the best preserved anywhere, and is held to be richer in its decoration than surviving Italian examples, ‘probably the most elaborate Cosmati pavement ever laid.’ ((Tatton-Brown, 1998, p. 61.)) It was also unique among Cosmati floors in including esoteric texts in brass letters, of which only a few now remain. Earlier recording, however, allows the recovery of the original wording with some certainty. The texts, three in number, may be reconstructed and rendered as follows:

XPI:MILLENO:BIS:CENTENO:DUODENO:

CUM:SEXAGENO:SUBDUCTIS:QUATUOR:ANNO: TERTIUS:HENRICUS:REX:URBS:ODORICUS:ET:ABBAS: HOS:COMPEGERE:PORPHYREOS:LAPIDES:

(In the year of Christ one thousand, two hundred, twelve

And sixty minus four [1268],

King Henry III, Odoric [of] the City [of Rome], and the Abbot

Put together these porphyry stones.)

SI: LECTOR: POSIT A: PRUDENTER: CUNCTA:REVOLVAT:

HIC:FINEM:PRIMI:MOBILIS:INVENIET:

SEPES:TRIMA:CANES:ET:EQUOS:HOMINESQUE:SUBADDAS:

CERVOS:ET:CORVOS:AQUILAS:IMMANIA: CETE:

MUNDUM:QUODQUE:SEQUENS.-PREEUNTIS: TRIPLICA T:ANNOS:

(If the reader carefully goes around,

He will here the [temporal] limits of the primum mobile discover:

A hedge, three [years], dogs and horses, men, added,

Stags and ravens, eagles, enormous whales,

The world. Each sequentially triples the years of the one before.)

SPERICUS:ARCHETIPUM:GLOBUS:HIC:MONSTRAT:MACROCOSMUM:

SPERICUS:ARCHETIPUM:GLOBUS:HIC:MONSTRAT:MACROCOSMUM:

(Here the globular sphere demonstrates the archetype of the macrocosm.) ((This reconstruction follows Foster; the rendering is my own paraphrase from the Latin.))

The first text is set around the square border of the whole mosaic, and relates to the everyday world of human endeavour, recording the authors and the date (albeit in an arcane and, it is suggested, numerologicaly significant, manner) of the pavement itself.

The second text outlines the pattern of the design’s central quincunx, and deals with the realm of nature. In this the total longevity of the universe, from the Creation ((Variously dated in the Middle Ages; Matthew Paris (Chron. Maj., ed. Luard, I, p. 81) gives 5199 BC.)) until Doomsday, is calculated according to a mathematical puzzle or riddle. The supposed life-spans of hedges, dogs, horses, men, stags, ravens, eagles and whales are added together, each being three times the years of its predecessor. The final answer is 19,683 years. The formula is largely traditional, being closely paralleled in the work of Hesiod, in a (possibly) ninth-century Irish poem preserved in the fifteenth-century book of Lismore, in an English folk-version, and elsewhere. ((Foster, 1991, pp. 101-3.))

The third text encircles the central disc itself, of Egyptian porphyry of richly swirling colours, a microcosm of the macrocosm, symbolising the realm of God and of spiritual things. Here, the ruler of Britain would be anointed and crowned. Similar discs were to be found in Hagia Sophia at the spot where Byzantine emperors were anointed, at Aachen in the palace chapel of Charlemagne and in Old St Peter’s, Rome, where the medieval German Kaisers were crowned by the Pope. ((Sayers, 2000.))

Whence came the inspiration to add the enigmatic texts, placed with geometrical significance, to the sanctuary pavement? Although descriptive labels exist on many floor-tiles, and longer texts were found on Westminster’s tiled chapter house floor, Italian stone pavements provided no precedent for ‘the philosophical sophistication of the cosmological text in the Cosmatesque work, or for the formal complexity of its integration into the design of the pavement’, ((Norton, 2002, pp. 21- 22; see also Tatton-Brown, 1998, p. 61.)) and Louis IX’s contemporary Sainte-Chapelle had no parallel. A spur, then, might be sought within Britain itself, and William of Malmesbury’s description of the floor which once had added mystery to Glastonbury’s most holy and awesome chapel offered a very apposite one. Foster notes William’s floor among examples of what Henry sought to achieve, and Norton finds his description ‘of interest for the symbolic meaning attached to the patterns by the Benedictine author. In a hesitant and rudimentary fashion it anticipates the symbolising cast of mind which we find explicitly expressed and literally writ large on the Westminster Sanctuary pavement.’ ((Foster, 1991, p. 147; Norton, 2002, p. 11. )) The fact that Glaston’s actual floor had almost certainly vanished before living memory allowed maximum scope for creative reinterpretation of William’s intriguing words about interlaced triangles and squares which, without injury to religion, encoded some sacred mystery. His words, indeed, might equally well be applied to Henry’s Westminster floor, whose individual stones were cut in the main as small triangles and squares; nor were they lost beneath dusty cobwebs on neglected library shelves. William’s Deeds of the Kings continued to be a well-known historical source, used, among others, by Matthew Paris. His monograph On the Antiquity of the Church of Glaston had been revised, in the years between Henry’s first visits, and his more splendid marking of the Feast of the Assumption with the Glastonbury community in 1250, to preface Adam of Domerham’s new chronicle, a literary re-vamping itself perhaps intended in part to convince the king of Glastonbury’s ancient pre-eminence.

Henry certainly used his travels as opportunities for research towards the beautification of Westminster, in which he took a most detailed personal interest. At Windsor in September 1249 he commanded Master John of St. Omer ‘to make a lectern to be placed in the new chapter-house at Westminster similar to the one in the chapter-house at St. Albans, and if possible even more handsome and beautiful; and for this purpose the king will arrange for the provision of colours and timber and for the necessary expenditure until the king returns to London.’ ((Colvin, 1963, p. 142; 1971, pp. 190-191. Close Rolls 1247-51, pp. 203, 245.)) Henry, and the advisors who helped him plan his aggrandisement of Westminster Abbey and the shrine of its Anglo-Saxon saint, are therefore unlikely to have neglected Glastonbury, burial-place of even more renowned Anglo-Saxon kings, as an exemplar. As Henry hoped that his Abbey would rival Louis’ Sainte-Chapelle, so he must have hoped it would outshine ancient Glastonbury, once England’s premiere abbey. A decision having been made to commission a cosmati floor for Westminster, William’s words would fall naturally into place. The reckoning of the years between Creation and Doomsday, and the demonstration of the ‘archetype of the macrocosm’ very happily fulfil the required ‘sacred mystery.’

5. Melkin’s ‘Little Sphere’s of Prophecy’

Henry’s works at Westminster were influential elsewhere. Roberts ((Roberts, 1985, pp. 134-5.)) argues for the stylistic dependence of the tympanum in the south porch at Lincoln Cathedral on a lost tympanum (known from drawings) over the north portal at Westminster Abbey. Here Christ at the Last Judgement indicates the wound on His side, a reference to the relic of the Holy Blood. The motif occurs also on the tomb of Bishop Giles de Bridport at Sailisbury (after 1262). Henry’s texts, also, were noted elsewhere, as we shall see. At Canterbury Cathedral the so-called Opus Alexandrinum, ((See above, note 4.)) a second, although less sophisticated, mosaic floor in imported marbles, which survives in the Trinity Chapel in front of the former site of Becket’s shrine, has received comparatively little study.

In the absence of contemporary documentation its date is uncertain. It may have been laid for Becket’s translation of 1220, but it has also been suggested that it was added in imitation of Henry’s Westminster floor after 1268. ((Sayers, 2000.)) Tatton-Brown and Norton, however, favour a date of 1182-84. ((Tatton-Brown, 1998, pp. 53-58; Norton, 2002, pp. 13-16. His suggestion (p. 15) that it re-used marble from the earlier Canterbury floor praised by William of Malmesbury is highly speculative)) This would make it just contemporary with William of Malmesbury’s Glastonbury floor, as the Great Fire did not occur until the summer of 1184. The base design of one square set diagonally within another resembles that at Westminster, although here the four larger circles have been drawn about the points where the inner square touches the mid-points of the outer squares’ sides. Parallels exist in Gothic window design etc., but the composition has none elsewhere among medieval floors; ((Norton, 2002, pp. 14-15.)) however it may also be seen as a modification of the Romano-British eight-pointed star pattern discussed above. If the earlier dating is indeed correct, then it may reflect elements not of Henry III’s Westminster floor but of that at Glastonbury.

In the absence of contemporary documentation its date is uncertain. It may have been laid for Becket’s translation of 1220, but it has also been suggested that it was added in imitation of Henry’s Westminster floor after 1268. ((Sayers, 2000.)) Tatton-Brown and Norton, however, favour a date of 1182-84. ((Tatton-Brown, 1998, pp. 53-58; Norton, 2002, pp. 13-16. His suggestion (p. 15) that it re-used marble from the earlier Canterbury floor praised by William of Malmesbury is highly speculative)) This would make it just contemporary with William of Malmesbury’s Glastonbury floor, as the Great Fire did not occur until the summer of 1184. The base design of one square set diagonally within another resembles that at Westminster, although here the four larger circles have been drawn about the points where the inner square touches the mid-points of the outer squares’ sides. Parallels exist in Gothic window design etc., but the composition has none elsewhere among medieval floors; ((Norton, 2002, pp. 14-15.)) however it may also be seen as a modification of the Romano-British eight-pointed star pattern discussed above. If the earlier dating is indeed correct, then it may reflect elements not of Henry III’s Westminster floor but of that at Glastonbury.

As a prominent ecclesiastic, the Abbot of Glastonbury, or his representative, was likely to have attended the ceremonies of the installation of the Holy Blood in 1247, and of the translation of the relics of the Confessor in 1268. As we have seen, Michael of Amesbury (1235-1252) enjoyed close relations with the king. Roger of Petherton, abbot 1261-1274, was less happily placed. In his time Walter Giffard, a crony of Henry, was made both Bishop of Bath and Wells and Chancellor of England, and revived old disputes with Glastonbury; Prince Edward, however, lent support to the monks. Even before his election as abbot in 1274, John of Taunton was an intimate of Edward I, acting as Abbot Roger’s emissary to the new king. Further troubles, however, followed the appointment of Edward’s friend Robert Burnell to the see of Bath and Wells in 1275.

At Easter 1278, such difficulties notwithstanding, Edward I made his famous ceremonial visit to Glastonbury to celebrate the feast with the monastic community, accompanied by Queen Eleanor and joined by the Archbishop of Canterbury. On the evening of the Tuesday in Easter week, Edward had the tomb in which Arthur’s remains had rested since their original discovery reopened. Within were found two chests (presumably of wood), one containing Arthur’s bones and one Guinevere’s, decorated with their likenesses and arms. The next day, 19 April, the bones of Arthur and Guinevere were re-wrapped in precious silks, by the King and Queen respectively, and replaced in the chests under their royal seals. The skulls and (rather oddly) the knee-caps, however, were kept on displayed for popular veneration. Edward ordered the tomb’s speedy (celeriter) removal to a site before the high altar, a position appropriate for a founder’s tomb, a project perhaps suggested by Henry’s translation of St Edward nine years before. ((Standen, 2000, pp. 507-8; Carley, 1985, pp. 242-247.)) The feretory chests were apparently placed in the church treasury until the work was completed, for it seems unlikely that the heavy stone monument was actually moved in the royal presence. ((The near-contemporary Annals of Waverley (Annales Monasterii de Waverleia, ed. H. R. Luard, Rolls Series 36, London 1864-69, Vol II, p. 389) state that they were so kept pending removal to a more honourable place. See Brown & Carley, 1993, p. 182.)) This grand ceremonial, involving the elaborate veneration of the royal relics, was certainly of the kind in which Henry III had so delighted, but its focus, the mighty emperor and crusader Arthur, embodied a very different model of kingship from that of the bloodless piety of the Confessor.

The tomb itself, apparently commissioned by Abbot Henry of Sully c.1190-1193, was of simple grandeur in dark stone, perhaps of Tournai marble, or the local blue lias limestone, waxed and polished, with twin lions at both head and foot. As reconstructed by Phillip Lindley it was a free-standing tomb chest with the lions under the corners as supporters. ((Lindley, 2007, pp. 151-158; I am grateful to Jerry Sampson for drawing this work to my attention.)) It is often stated that Edward and Eleanor themselves deposited the remains in a new tomb in 1278, ((E.g. Parsons, 1993, p. 173-4.)) but Adam of Domerham’s account makes it clear that this was not the case. A fresh study of the documentation for the tomb and its epitaphs in conjunction with the reassesment of the fabric and building phases at the Abbey currently underway would be helpful. Its location before Edward’s visit is unclear. Adam of Domerham, who would have known, clearly states that it stood in the Great Church. ((Standen, 2000, p. 52.)) Almost certainly it would have stood somewhere at the eastern end, where rebuilding began after the fire of 1184, and the retro-choir would be a reasonable guess, although Leland, in the sixteenth century, thought that at some stage it had stood in the south transept near the treasury. ((Brown & Carley, 1993, p. 183; Lindley, 2007, p. 150.)) Nitze’s contradictory assertion in 1934 that it was located in the Lady Chapel was based on mistaken assumptions about the rate of re-building. The tomb was moved once more in 1368 when the choir was extended and the high altar shifted eastwards, and so the site now marked in the Abbey ruins may not be exactly correct. Some appropriate and tasteful modern representation of the tomb to replace the current muddy patch before a curbed outline and an inaccurate metal sign would be most desirable and would enhance the visitor’s appreciation of the Abbey.

Edward’s own Westminster tomb was similarly to be of black stone, in his case Purbeck marble, and plain, ((The notorious painted text ‘Hammer of the Scots’ was added well after Edward’s own time.)) in contrast to that planned for, and probably by, his father. It was, indeed, at around the time of Edward’s visit to Glastonbury that Peter Oderic and the Italian cosmati craftsmen returned to England once more to work on the tomb of Henry III.

The timing of Edward’s visit to Glastonbury was far from arbitrary in political terms. It came in the aftermath of his successful first Welsh war, in which he had humbled Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, who had been a thorn in his side since his father had granted him the County Palatinate of Chester and the Crown’s lands in Wales at the age of 15 in 1254. Llewelyn ‘the Last’ had assumed the title of Prince of Wales in 1258 and exploited the Crown’s weakness at the time of the baronial wars. His title was confirmed in the Peace of Montgomery of 1267. He discourteously failed to attend Edward’s coronation, and refused to do him customary homage on the grounds that Edward was sheltering his Welsh rivals, including his own brother Dafydd. His intended marriage to the daughter of the late Simon de Montfort, Edward’s one-time mentor and eventual enemy, caused further friction and Edward had her detained. In November 1276, his patience exhausted, Edward resolved on war, personally advancing into North Wales in the second half of 1277 in an unspectacular campaign which resulted in the submission of Llewelyn in mid-November in the Treaty of Aberconway. The terms were surprisingly moderate. Llewelyn retained his title, spent Christmas with the King at Westminster, and was eventually allowed to marry Eleanor de Montfort with much ceremony at Worcester in October 1278. Edward even paid for the wedding, which he attended.

The Easter of 1278, therefore, was, in the Arthurian literary tradition, the next great ceremonial ‘crown wearing’ to following the Christmas celebrations with Llewelyn. Edward could bask in the Arthurian spring sunshine as undisputed overlord of the British Isles, secure in his reputation as a brave, chivalrous and undefeated crusader, whose smooth succession had been universally welcomed. Renewed hostilities with the Welsh, leading to the anticlimactic death of Llewelyn, the last native Prince of Wales, and the firm subjection of Snowdonia in the famous castle-building programme, would not begin until 1282. ((It was after this campaign that Arthur’s supposed crown was presented to Westminster Abbey.)) Edward’s relations with his brother-in-law and vassal Alexander III of Scotland were harmonious. The Scottish wars which were to follow the latter’s untimely death in a riding accident in 1286 and the equally unhappy death of his granddaughter and heir Margaret, the seven-year-old Maid of Norway, in 1290, and were to spoil Edward’s later years and mar his reputation, were as yet far ahead. For the time being the Isles were peaceful and prosperous. Edward, with his Arthurian ceremony, could draw a definitive line under the unfortunate aspects of his father’s reign and set the tone of his own very different style of kingship. In contrast to his father’s translation of the un-heroic Confessor, Edward and his beloved Queen Eleanor, with appropriate ceremony, commanded the re-interment of Arthur and Guinevere, flower of kings and most romantic of queens, before the high altar as the central focus in the completed church where the great sovereigns of the Anglo-Saxon golden age also lay at rest, including Edgar the Peaceable, whose imperial sway, like that of Arthur, had embraced all Britain. ((By the time Leland saw Arthur’s tomb in the 16th century, it was flanked to the north by one for Edmund I and to the south by another for Edmund II. Under the last two Abbots, Edgar, revered here as a saint, acquired an elaborate chapel of his own at the Abbey’s eastern end. See Lindley, 2007, p. 151.)) The lesson that Edward himself now wore the mantle of Arthur, national hero of the Welsh, was surely too obvious to need emphasis. ((Contra Prestwich, 1988, who notes (in a general discussion of Edward’s attitude to Arthur, pp. 120-22) that ‘no overt connection’ was made with the Welsh campaign, and that no ‘tournament or other chivalric activity’ accompanied the translation.)) As David Standen put it, ‘the king was clearly trying to forge a link, spiritually and physically, between himself and the legendary Arthur.’ ((Standen, 2000, p. 24.))

Glastonbury, too, will have found the ceremony timely, demonstrating as it did its unique national status and renewed royal favour following the recent revival of difficulties with Wells. It may also have found satisfaction in the fact that Edward’s veneration for Westminster was less marked than his father’s had been. In the High Middle Ages, ceremonial and symbol were important for churches no less than for kings. Henry III’s programme at Westminster, comprising the institution of a cult of the Holy Blood and the translation and elaborate commemoration of a nationally significant saintly figure, may be seen as a creative stimulus to parallel developments at the older, and at one time senior, Benedictine house.

These appear most clearly in the enigmatic ‘Prophecy of Melkin’, included in the Chronica of the monk John ‘of Glastonbury’ (John Sheen) of 1342, which built upon the work of William of Malmesbury and Adam of Domerham. The previously unheard-of character of Melkin, who was ‘before Merlin,’ is presented in the same vaticinatory pseudo-Welsh tradition as the Arthurian seer as imagined by Geoffrey of Monmouth, and the Latin is therefore deliberately cryptic. Here we read for the first time of the burial of Joseph of Arimathea at Glastonbury, in a hidden tomb which will be revealed at a millennial future time before the Day of Judgement. He lies (as I have argued elsewhere ((Ashdown, 2003.)) ) in a folded linen shroud, probably to be identified with that of Christ, and with two vessels containing (presumably one of each) Christ’s blood and sweat:

Insula Auallonis auida funere paganorum, pre ceteris in orbe ad sepulturam eorum omnium sperulis prophecie uaticinantibus decorata et in futururn ornata erit altissimum laudantibus. Abbadare potens in Saphat paganorum nobilissirnus cum centum quatuor milibus dormicionem ibi accepit. Inter quos Ioseph de marmore ab Arirnathia nomine cepit sompnum perpetuum. Et iacet in linea bifurcata iuxta meridianum angulum oratorii, cratibus preparatis, super potentem adorandam uirginem, supradictis sperulatis locum habitantibus tredecim. Habet enim secum Ioseph in sarcophago duo fassula alba el argentea, cruore prophete Ihesu et sudore perirnpleta. Cum reperietur eius sarcophagum integrum illibatum, in futuris videbitur et erit apertum toto orbi terrarum. Ex tunc nec aqua neec ros celi insulam nobilissimam habitantibus poterit deficere. Per multum tempus ante diem iudicialem in Iosaphat erunt aperta hec et viuentibus declarata. ((Carley, 1981, pp. 2-3; 1985, pp. 28-31.))

The Isle of Avalon, avid before others in the world for the death of pagans, decorated at the sepulchre of them all with vaticinatory little spheres of prophecy, and in future it will be adorned with those who praise the Most High. Abbadare, powerful in Saphat, noblest of pagans, took his sleep there with 104,000. Among them Joseph named ‘of Arimathea’, took perpetual sleep in [a] marble [tomb]. And he lies in a doubled linen [cloth] by the southern corner of the oratory fashioned of wattles, above the powerful adorable Virgin, the aforesaid thirteen sphered [things] inhabiting the place. For Joseph has with him in the sarcophagus two white and silver vessels filled with the blood and sweat of the prophet Jesus. When his sarcophagus is found, it will be seen whole and undefiled in the future, and will be open to all the orb of the earth. From then on, neither water nor heavenly dew will can be lacking for those who inhabit the most noble island. For a long time before the Day of Judgement in Josaphat these things will be open and declared to the living.

This rigmarole may well incorporate older elements but, in the form in which we have it, is datable to the aftermath of Edward I’s visit through the inclusion of the figure of Abbadare. As first suggested in 1981 by James Carley, he is to be identified with Baybars (in Arabic al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari), Sultan of Egypt and Syria, Edward’s formidable adversary during the Ninth Crusade, who had captured the fortress of Safed, Melkin’s ‘Saphat,’ (and with it the Galilee) from the Templars in 1266, and died of poisoning in July 1277, in the year before Edward’s visit to Glastonbury. I have argued elsewhere that Melkin’s reference originated in some satirical lay which had consigned the deceased Baybars and his paladins to one of the alternative Mediterranean, Oriental or Antipodean locations of an Avalon which has here been repatriated, along (uncomprehendingly) with the Sultan, to its British origin. ((Carley, 1981, p. 10; Ashdown, 2003, pp. 178-181.))

Included among the sleeping ‘pagans’ (i.e., in contemporary usage, Muslims), perhaps because of his status as a wealthy Jew, is Joseph of Arimathea. Although ‘Melkin’ is the oldest source to tell of his burial at Glastonbury, his tomb’s exact location is clearly regarded as an occult secret. It seems most unlikely that John Sheen was himself the author of the Melkin doggerel. Indeed, he seems to have been the first to confuse the mysterious linea bifurcata, which I have interpreted as a shroud, with some kind of esoteric line in church or churchyard. John Leland, in the sixteenth century, claimed to have seen other manuscript material attributed to Melkin in Glastonbury Abbey’s library and, perhaps significantly, John Bale, writing in 1548, wrote of Melkin as an astrologer (specialising in comets) and a geometer. ((Carley, 1981, pp. 4-6.))

The puzzling gift of water and heavenly dew, so superfluous on Glaston’s riverine island, may partially reflect the older legend of St Benignus at Meare, who was responsible for ending a water-shortage, but is probably to be understood in the light of biblical prophecy. Ezekiel, exiled in Babylon, is transported in spirit to witness the renewed Jerusalem that is to replace that destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar. He is taken by an angel to the entrance of the Temple, ‘and I saw water coming out from under the threshold of the temple towards the east (for the temple faced east). The water was coming down from under the south side of the temple, south of the altar.’ The stream becomes a river flowing down to the Dead Sea, turning its salt water to fresh. Many fish will live where it flows. ‘Fruit trees of all kinds will grow on both banks of the river. Their leaves will not wither, nor will their fruit fail. Every month they will bear fruit, because the water from the sanctuary flows to them. Their fruit will serve for food and their leaves for healing’ (Ez. 47:1-12, New International Version).

The image is taken up in Revelation 22:1-2, in St John’s vision of the New Jerusalem: ‘Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, as clear as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb down the middle of the great street of the city. On each side of the river stood the tree [sic] of life, bearing twelve crops of fruit, yielding its fruit every month. And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.’ The biblical trees find a resonance in Glastonbury’s miraculous trees, the twice-flowering Holy Thorn, and the walnut which withheld its leaves until St Barnabas’ Day, 11 June, the date of the re-consecration of the Lady Chapel in 1186 (although we do not hear of these until the early sixteenth century). ((The biblical prophecies seem also to have informed the dream of Matthew Chancellor in 1750, which inspired him to discover the supposed medicinal properties of the Glastonbury waters, which flowed from the Abbey grounds into Magdalene Street.))

That Glastonbury already saw itself as the New Jerusalem is made certain by another quotation by John of Glastonbury, significantly of interpolated lines in the Abbey’s copy of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Life of Merlin, where it is said of Glaston: ‘This was the New Jerusalem…’ ((Carley, 1985, pp. 12-13.)) Ezekiel’s localisation of the healing water as ‘coming down from under the south side of the temple, south of the altar’ was mirrored at Glastonbury, where an ancient well, which once had its own exterior well-house, is now approached from the crypt of the Lady Chapel near its original south-eastern corner. The well is fed by its own spring, and although the present crypt dates only from the abbacy of Richard Beere (1494-1525) the well-shaft may be Roman, and the spring was probably a partial determinant for the original site of the Chapel. This is the area, ‘by the southern corner of the oratory fashioned of wattles,’ which Melkin singles out as Joseph’s burial place, and, as in Ezekiel’s scheme, it lies to the south of what would have been the main altar. Perhaps this is what the phrase super potentem adorandam uirginem, ‘above the powerful adorable Virgin’ intends to indicate, signifying ‘to the right of’’ rather than ‘higher than’ or ‘beyond’. It is notable that St Patrick, Joseph’s predecessor as supposed founder, had also been buried in a ‘pyramid’ to the south of the altar. The precise original disposition of the east end of the ‘Old Church’, either in reality or as imagined by the Melkin author, of course, must remain conjectural; a scorched wooden image of the Virgin which had miraculously survived the fire of 1184 ((Scott, 1981, pp. 80-81.)) was the central object of devotion in the stone Romanesque Lady Chapel which replaced it, however, appearing on the older of Glastonbury’s surviving seals. The arrangement of the shrine associated with this may have had some bearing on Melkin’s words.

In Melkin’s prophecy, as many have noted, Joseph’s cruets of blood and sweat are substituted for the Grail of the romances. Here, surely, we may detect the influence of Grosseteste. If Glastonbury had been uncertain how to respond to the Grail-literature which had publicised Joseph of Arimathea as the apostolic founder of British Christianity, a role long claimed for Glastonbury’s anonymous apostolic founders, as the footnote to the Trinity manuscript suggests, then the way was made clear by Grosseteste’s thesis on the Holy Blood of Westminster. By the ‘white and silver’ containers, we are surely meant to understand crystal vessels mounted with silver, like the ‘pyx’ sent to Henry III and illustrated by Matthew Paris. For the possibility that Glastonbury itself held a copy of Matthew Paris’s Chronica Majora, a text not widely known outside St Alban’s, and to which the only known copy of Grosseteste’s ‘determination’ was appended, see Julian Luxford’s discussion of a version of Paris’s drawing of the Holy Blood procession apparently made at the Carthusian monastery of Witham, Somerset, in the fifteenth century. ((Luxford, 2009, pp. 97-99.))